_10_Theology as Doctrine

Since subjective theology is the aptitude to teach no more and no less than God’s Word 78 as the Church of our day possesses it in the written Word of the Apostles and Prophets,79 objective theology, theology in the sense of doctrine, is nothing more and nothing less than the presentation in oral and written form of the doctrine presented in Holy Scripture. The Christian doctrine is not produced by the theologian; all that the Christian theologian does is that he compiles the doctrinal statements contained in Scripture (in the text and context), groups them under their proper heads, and arranges these doctrines in the order of their relationship. Accordingly, objective theology (theologia positiva) is, as our old Lutheran dogmaticians say, nothing else than Scripture itself arranged according to doctrines; hence all the parts that go to make up this body of doctrine (corpus doctrinae), the least important no less than the most important articles, must be based on Scripture.80 All theologians since the days of the Apostles, says Luther, must confine themselves in their teaching to the teaching of the Apostles: “We are catechumens and pupils of the Prophets. Let us simply repeat and preach what we have heard and learned from the Prophets and Apostles” (St. L. III:1890). Luther enforces the demand that the theologians simply “repeat the words of the Apostles after them” with the solemn warning: “Neither ought any doctrine be taught or heard in the Church but the pure Word of God, that is to say, the Holy Scriptures; otherwise accursed be both the teachers and hearers together with their doctrine.”81 The same truth is expressed in the well-known axiom: Quod non est biblicum, non est theologicum.

It follows that (Christian) theology is not made up of the variable notions and opinions of men, but is the immutable divine truth or God’s own doctrine (doctrina divina). It has this quality because of the source from which it is drawn. According to the witness of Christ and His Apostles and its own self-attestation in the hearts of the Christians, Holy Scripture is God’s infallible Word, and therefore the doctrine taken from the Scripture is not “after the tradition of men” (Col. 2:8), not man’s doctrine, but God’s own doctrine, “the doctrine of God our Savior” (Titus 2:10). And in God’s Church nothing but God’s own doctrine may be preached and heard. The door of the Church is closed to all doctrines devised by men.

This truth needs to be stressed in view of the contrary claims of modem theology. The moderns have nothing to offer but human doctrine. Refusing to accept Scripture as the Word of God, they have found it theologically unreliable and have substituted for it as the source of doctrine the human heart, the theological Ego. And they insist that the Church accept the results of their theological cogitations as the true theology. They are virtually demanding that theology be removed from the realm of the objective divine truth into the sphere of subjective human opinion. Because of the insistent claims of the modern theologians that the Church is well served by this human theology we shall have to insist that what the Church needs is God’s theology and that the theology, the doctrine drawn by the theologian from Scripture (doctrina e Scriptura Sacra hausta), is divine doctrine, doctrina divina. And this not merely in the sense that it tells of God and divine things but particularly and primo loco in the sense that such doctrine, in contrast to all human doctrines, views, and judgments, is God’s own doctrine, view, and judgment.

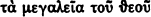

To illustrate: Concerning the creation of the world and man the Christian theologian teaches what God has told him in Genesis 1 and 2 and elsewhere in Scripture; and so his doctrine is divine doctrine. When he is forced to take note of the stories told by human cosmogonists, he rejects whatever does not agree with the Biblical cosmogony as worthless human speculation. — Concerning the Fall and the nature of sin the Christian theologian teaches no more and no less than what God reports, pronounces, and teaches on this matter in Holy Scripture. He must here, too, take note of a great mass of human speculation on the origin of sin, its nature, and its consequences. But whatever is contrary to the teaching of Scripture, which cannot be broken, he rejects at once as man’s antithesis to God’s own thesis. — Concerning the redemption of fallen mankind, i. e., the incarnation of the eternal Son of God, the person and work of the Savior, the Christian theologian teaches only what God Himself teaches concerning these great things ( , Acts 2:11). These wonderful things never entered into the heart of man (1 Cor. 2:9; John 1:18). They constitute a “mystery which was kept secret since the world began,” but are “now made manifest by the Scriptures of the Prophets,” by God Himself (Rom. 16:25-26; Eph. 3:7-12). Therefore the Christian theologian renounces all human speculations and insists that God be heard. Modern theology insists on the right of man to judge these matters, finds fault with the divine method of redemption, particularly with the substitutionary satisfaction of Christ, as being too “juridical,” and refuses to teach it. However, this attempt to silence God’s voice and suppress the divine doctrine of redemption can have only one effect on the Christian theologian: He will the more loudly proclaim what the Scriptures of the Old and the New Testament teach, redemption through the vicarious satisfaction of Christ.82 — On the articulus stantis et cadentis ecclesiae, the doctrine of justification before God, the Christian theologian teaches that man obtains the forgiveness of sins by faith (

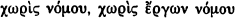

, Acts 2:11). These wonderful things never entered into the heart of man (1 Cor. 2:9; John 1:18). They constitute a “mystery which was kept secret since the world began,” but are “now made manifest by the Scriptures of the Prophets,” by God Himself (Rom. 16:25-26; Eph. 3:7-12). Therefore the Christian theologian renounces all human speculations and insists that God be heard. Modern theology insists on the right of man to judge these matters, finds fault with the divine method of redemption, particularly with the substitutionary satisfaction of Christ, as being too “juridical,” and refuses to teach it. However, this attempt to silence God’s voice and suppress the divine doctrine of redemption can have only one effect on the Christian theologian: He will the more loudly proclaim what the Scriptures of the Old and the New Testament teach, redemption through the vicarious satisfaction of Christ.82 — On the articulus stantis et cadentis ecclesiae, the doctrine of justification before God, the Christian theologian teaches that man obtains the forgiveness of sins by faith ( ), that is, through faith in the Gospel, which forgives sins for the sake of Christ’s atoning sacrifice, without the Law and without the works of the Law (

), that is, through faith in the Gospel, which forgives sins for the sake of Christ’s atoning sacrifice, without the Law and without the works of the Law ( ), that is, without demanding any moral quality in man or any ethical achievement as contributing factors in justification. Neither Rome’s anathema nor the protests of degenerate Protestantism, which reject the divine mode of justification as too external and juridical, nor the antagonism of his own natural heart, in which the opinio legis inheres naturaliter, can induce the Christian theologian to change the Scripture doctrine of justification, “even though heaven and earth and whatever will not abide, should sink to ruin” (Smalc. Art., Trigl., 461, 5). The Christian theologian as such is a realist. He knows from his own experience what the disquieted sinner needs. He realizes what a terrible thing it would be if the terrified sinner, who wants to know about the way of salvation, had to rely on human opinions. The sinner wants absolutely reliable information on the question of justification. Nothing but God’s own doctrine will serve him. — And this applies to all parts of the Christian doctrine, including the doctrines of eternal damnation and of eternal salvation. In short, the Christian theologian teaches only God’s doctrine, as set down in Holy Scripture, “God’s Book” (Luther’s phrase; St. L. IX:1071). He does not deal with human thoughts and opinions.

), that is, without demanding any moral quality in man or any ethical achievement as contributing factors in justification. Neither Rome’s anathema nor the protests of degenerate Protestantism, which reject the divine mode of justification as too external and juridical, nor the antagonism of his own natural heart, in which the opinio legis inheres naturaliter, can induce the Christian theologian to change the Scripture doctrine of justification, “even though heaven and earth and whatever will not abide, should sink to ruin” (Smalc. Art., Trigl., 461, 5). The Christian theologian as such is a realist. He knows from his own experience what the disquieted sinner needs. He realizes what a terrible thing it would be if the terrified sinner, who wants to know about the way of salvation, had to rely on human opinions. The sinner wants absolutely reliable information on the question of justification. Nothing but God’s own doctrine will serve him. — And this applies to all parts of the Christian doctrine, including the doctrines of eternal damnation and of eternal salvation. In short, the Christian theologian teaches only God’s doctrine, as set down in Holy Scripture, “God’s Book” (Luther’s phrase; St. L. IX:1071). He does not deal with human thoughts and opinions.

Holy Scripture holds him to such teaching. Holy Scripture makes the absolute demand that the doctrine taught in the Church be doctrina divina. The Holy Scriptures of the Old and the New Testament are full of warnings against those teachers who will not confine themselves to teaching God’s Word, but feel free to proclaim their own thoughts. Read the solemn words of Jer. 23:16: “Thus saith the Lord of Hosts, Hearken not unto the words of the prophets that prophesy unto you; they make you vain [R. V., they teach you vanity]; they speak a vision of their own heart [ .: they tell you fancies of their own] and not out of the mouth of the Lord.” 83 In like manner the entire New Testament proscribes the teaching of human thoughts and opinions and enjoins all teachers to speak out of the mouth of the Lord. Whoever opens his mouth to teach in the Church, which is “the house of God” (1 Tim. 3:15), should speak God’s Word,

.: they tell you fancies of their own] and not out of the mouth of the Lord.” 83 In like manner the entire New Testament proscribes the teaching of human thoughts and opinions and enjoins all teachers to speak out of the mouth of the Lord. Whoever opens his mouth to teach in the Church, which is “the house of God” (1 Tim. 3:15), should speak God’s Word,  (1 Pet. 4:11).84 Whoever teaches otherwise [

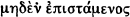

(1 Pet. 4:11).84 Whoever teaches otherwise [ ] and does not adhere to the wholesome words of our Lord Jesus Christ, as we have them in the Word of His Apostles (John 8:31-32 compared with John 17:20), is unfit for the office of teaching in the Christian Church; for in place of teaching the divine truth such a one is bloated (

] and does not adhere to the wholesome words of our Lord Jesus Christ, as we have them in the Word of His Apostles (John 8:31-32 compared with John 17:20), is unfit for the office of teaching in the Christian Church; for in place of teaching the divine truth such a one is bloated ( ) with his own human opinion, and he knows nothing (

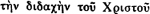

) with his own human opinion, and he knows nothing ( ) but is sick with disputations and strifes about words (1 Tim. 6:3 f.). The Christians are therefore forbidden, both by the Old and the New Testament (2 John 8-11; Rom. 16:17), to fellowship those teachers who do not bring Christ’s doctrine (

) but is sick with disputations and strifes about words (1 Tim. 6:3 f.). The Christians are therefore forbidden, both by the Old and the New Testament (2 John 8-11; Rom. 16:17), to fellowship those teachers who do not bring Christ’s doctrine ( ), that is, God’s doctrine, because such teachers by bringing in their own doctrine “cause divisions and offenses” in the Church, rob the Christians of their Christian treasures (2 John 8), and do not perform the “good work” of a Christian teacher (1 Tim. 3:1), but are engaged in “evil deeds” (2 John 11). Scripture thus declares in the strongest possible way that the doctrine proclaimed in the Christian Church must be God’s own doctrine, doctrina divina.

), that is, God’s doctrine, because such teachers by bringing in their own doctrine “cause divisions and offenses” in the Church, rob the Christians of their Christian treasures (2 John 8), and do not perform the “good work” of a Christian teacher (1 Tim. 3:1), but are engaged in “evil deeds” (2 John 11). Scripture thus declares in the strongest possible way that the doctrine proclaimed in the Christian Church must be God’s own doctrine, doctrina divina.

Luther upholds this demand of Scripture with might and main. Recall his urgent words: “O theologians, how are you going to escape here? Do you consider it a trifling matter when the Supreme Majesty forbids whatever does not proceed out of the mouth of the Lord and is something else than God’s Word?” (On Jer. 23:16. St. L. XIX:821.) Feeling deeply about this matter, Luther stressed the necessitas doctrinae divinae in ecclesia tradendae et audiendae from various points of view. He points, for instance, to the difference between State and Church and says that in “the government of the world and the home” human opinions and the word of man are in place, for this territory is ruled by the “natural light,” that is, by human reason. But teaching in the Church is a different matter: “If any man would preach, let him suppress his own words…. Here in the Church he must utter nothing but the words of the rich head of the family; otherwise it is not the true Church. Therefore it must be thus: God is speaking.” (St. L. XII: 1413.) Luther expresses this same thought in his somewhat paradoxical statement that the Christian doctrine “does not belong in the Lord’s Prayer.” The meaning is that it should not be necessary for the preacher to ask God’s forgiveness for the doctrine he has preached; he should rather be in a position to say: “It is God’s Word and not mine, and so there can be no reason for His forgiving me; He can only confirm, praise, and crown what I have preached, saying, ‘Thou hast taught correctly, for I have spoken through thee, and the Word is Mine.’ ” Luther adds the weighty words: “Whoever cannot truthfully say that of his sermon should quit preaching, for he must surely be lying and blaspheming God when he preaches.” (St. L. XVII: 1343 f. Cp. VIII:37.)

Luther takes this matter up again when he discusses the authority of the Christian Church. He denies that the Church has the authority to make Christian doctrine or to decree articles of faith, because the Church has and proclaims no word of its own, but only Christ’s Word. The Church repudiates every teaching which is not Christ’s Word, “Though a lot of this gabbling is going on, the Church has no part in the prattle. Let them cry and rave, ‘Church, Church!’; without God’s Word it amounts to nothing.” (St. L. XII:1414.)

And Luther applies this also to those teachers who are held to be theologians par excellence, the professors of theology. Some modern theologians take the position that while the ordinary preacher should content himself with teaching the doctrine as Scripture presents it, this restriction must not be laid upon the divinity professors, who owe a duty to the scientific method.85 Luther does not share that view. He tells the university theologians that they, too, must exercise the strictest mental discipline; they must, without mercy, banish from their minds all thoughts about God and divine matters which are not clearly expressed in the words of Scripture. Luther adduces his own example. It is inevitable, he says, that our own thoughts intrude into our study of the high matters pertaining to God and divine things; he, too, found all sorts of notions arising in his mind, but God had granted him the grace to submerge all thoughts that were outside Scripture. Zwingli and his associates said that Luther was without “spirit”; they condemned this clinging to the words of Scripture as mere intellectual knowledge, letter worship, dead theology; the “spirit” must be given the reins. Luther replied that if he had wanted to give free play to the “spirit,” he could perhaps have originated more thoughts of his own than all “enthusiasts” together, but he had no right to foist his own notions on the Church. “Oh, how many fine ideas occurred to me which I had to dismiss! If an ‘enthusiast’ had so many fine notions, he would not find enough printing presses to tell the Church about them.” (St. L. XX:792.) Moreover, says Luther, it is not the Holy Spirit that urges you to have your own thoughts about God and divine matters. The Holy Spirit would have us be “catechumens and pupils of the Prophets”; “we repeat and preach what we have heard and learned from the Prophets and Apostles.” (St. L. III:1890.)

To some the use of the word “repeat” (nachsagen) in this connection is offensive. Now, Luther does not mean that the Christian teacher “must not use more words and other words than are found in Scripture,” for that is untenable. (St. L. XVI:2212.) But he purposely uses the strong word “repeat”; he would emphasize as strongly as possible that the Christian teacher “should teach nothing in divine matters outside Scripture.” His doctrine should be, as to its content, simply a reproduction of the doctrine of the Prophets and Apostles, without any admixture of his own human views. All true teachers of the Church are so constituted, says Luther, that “they present nothing original or new, as the Prophets did, but teach only what they get from the Prophets” (St. L. III:1890). – The teachers at the theological schools of the Missouri Synod are not overdoing it when they ask their students to examine and re-examine their completed sermons for the purpose of detecting, and mercilessly deleting, any non-Scriptural thought that may have crept in, because it has no right to be heard in the Church of God, which is built on the foundation of the Apostles and Prophets.

Our old Lutheran theologians, too, insist on the doctrina divina. For them theology is simply the compilation, systematizing of the divine doctrine contained in Scripture. The Christian doctrine is doctrina e revelatione divina hausta; doctrina ex Verbo Dei exstructa, etc. Nothing must be injected into the corpus doctrinae of the Church which is not contained in Scripture. And in order to accentuate this characteristic feature of the Christian doctrine, they have called objective theology theologia  , ectypal, or derived, theology, that is, a reproduction, re-presentation, of the theologia

, ectypal, or derived, theology, that is, a reproduction, re-presentation, of the theologia  , the archetypal, or original, theology, which is that knowledge of God and divine things originally found only in God, but which God has graciously communicated to man through His Word.

, the archetypal, or original, theology, which is that knowledge of God and divine things originally found only in God, but which God has graciously communicated to man through His Word.

Some think that this terminology serves no purpose and is outmoded.86 But it is thoroughly Scriptural, and the theologians of all ages can profit by it. Rudelbach says: “I do not know whether anyone has pointed out that this distinction (between theologia  and

and  ), which brings out the true nature of theology, is based on Scripture. Nevertheless it is clearly taught in the words of the Lord (Matt. 11:27): ‘No man knoweth the Son but the Father; neither knoweth any man the Father save the Son and he to whomsoever the Son will reveal Him.’”87 Our old theologians furnish abundant proof for the Scripturalness of this distinction. Scherzer, for instance, writes: “Theologia

), which brings out the true nature of theology, is based on Scripture. Nevertheless it is clearly taught in the words of the Lord (Matt. 11:27): ‘No man knoweth the Son but the Father; neither knoweth any man the Father save the Son and he to whomsoever the Son will reveal Him.’”87 Our old theologians furnish abundant proof for the Scripturalness of this distinction. Scherzer, for instance, writes: “Theologia  is God’s own knowledge of Himself (Matt. 11:27; 1 Cor. 2:10 f.).”88 The old theologians develop the following thoughts: (1) Only God knows God; God dwells in a light which no man can approach unto (1 Tim. 6:16; 1 Cor. 2:10-11; John 1:18 a; Matt. 11:27). (2)God stepped out of this unapproachable light and revealed Himself to man, so that man can, in a measure, know God. He reveals Himself to man in the realm of nature and through His Word. God’s self-revelation in nature (Rom. 1:19 ff., 32; 2:14-15; Acts 14:17; 17:26-27) is the source of natural theology, of the natural knowledge of God. God’s revelation of Himself in the Word (John 1:18b; 8:31-32; Eph. 2:20) is the source, and the only source, of Christian theology, of the saving knowledge of God. Since man can know God only as He has revealed Himself, and since He has revealed Himself as the God of our salvation in the Word, Christian theology must be ectypal; it cannot be anything else than an exact replica of the divine doctrine contained in Scripture. Gerhard’s presentation of this matter is worth reading.89 Luther is describing the theologia

is God’s own knowledge of Himself (Matt. 11:27; 1 Cor. 2:10 f.).”88 The old theologians develop the following thoughts: (1) Only God knows God; God dwells in a light which no man can approach unto (1 Tim. 6:16; 1 Cor. 2:10-11; John 1:18 a; Matt. 11:27). (2)God stepped out of this unapproachable light and revealed Himself to man, so that man can, in a measure, know God. He reveals Himself to man in the realm of nature and through His Word. God’s self-revelation in nature (Rom. 1:19 ff., 32; 2:14-15; Acts 14:17; 17:26-27) is the source of natural theology, of the natural knowledge of God. God’s revelation of Himself in the Word (John 1:18b; 8:31-32; Eph. 2:20) is the source, and the only source, of Christian theology, of the saving knowledge of God. Since man can know God only as He has revealed Himself, and since He has revealed Himself as the God of our salvation in the Word, Christian theology must be ectypal; it cannot be anything else than an exact replica of the divine doctrine contained in Scripture. Gerhard’s presentation of this matter is worth reading.89 Luther is describing the theologia  when he says that the Christian teachers are not “Prophets,” but “children of the Prophets,” “catechumens and pupils of the Prophets,” who simply repeat and preach what they have heard and learned from the Prophets. And when Scherzer, for instance, classifies the theology which does not conform to the original type (theologia

when he says that the Christian teachers are not “Prophets,” but “children of the Prophets,” “catechumens and pupils of the Prophets,” who simply repeat and preach what they have heard and learned from the Prophets. And when Scherzer, for instance, classifies the theology which does not conform to the original type (theologia  ) as mataeologia (vain theology), as heretical, empty babbling,90 that was not a novum in Lutheran theology. Already Luther had said: Whatever is taught in the Church without Scripture is not the Church’s doctrine; it is silly “prattle.”

) as mataeologia (vain theology), as heretical, empty babbling,90 that was not a novum in Lutheran theology. Already Luther had said: Whatever is taught in the Church without Scripture is not the Church’s doctrine; it is silly “prattle.”

Modern theology flatly rejects the thesis that the Christian doctrine is doctrina divina and in no way doctrina humana. It must do so because it no longer believes that Scripture is the Word of God. When Luther requires the theologian to discard every thought that is not taken from the words of Scripture, and when the dogmaticians recognize only that teaching as Christian which is theologia  , the reproduction of the Scripture doctrine, that is due to the fact that they — both Luther and the dogmaticians — regard Scripture as God’s own Word, as “God’s mouth.” But the modern theologians refuse to recognize Scripture as God’s Word.91 They insist that the only scientifically correct method is to draw on “the pious self-consciousness of the theologizing individual.” 92 Thus they do not base their theology on the objective divine truth, but on subjective human opinions. That has produced the situation so aptly described by Luther in the well-known words which Hase made the motto of his Hutterus Redivivus: “They all have something to sell. Their aim is not to reveal Christ and His mystery, but their own mystery. They think more of that than of the mystery of Christ. Their own beautiful thoughts must not go to waste. Through them they hope to convert even the devils, while they have never yet converted a gnat. And the worst of it is, all they do is pervert the truth.” (St. L. XIV:397.) Naturally, everyone prefers his own brand. And so there is in modern theology no longer any unanimity of doctrine. The moderns do not attempt to hide this situation. Recall the statement of Nitzsch-Stephan: The unanimity in the acceptance of the principle that the Christian doctrine must not be taken from the Bible but out of the pious self-consciousness is accompanied by “uncounted divergencies” of theological trends (Lehrbuch, pp. 16 and IX). Nor does modern theology deplore the chaotic condition that has resulted from the repudiation of the Scripture principle. It has sunk so far below the Christian level that it prizes “the divergent trends” in theology as embellishments of the Christian Church and brands the agreement in doctrine and faith, which Scripture clearly demands,93 as an abnormality, as a “repristination” of an outmoded theological position.

, the reproduction of the Scripture doctrine, that is due to the fact that they — both Luther and the dogmaticians — regard Scripture as God’s own Word, as “God’s mouth.” But the modern theologians refuse to recognize Scripture as God’s Word.91 They insist that the only scientifically correct method is to draw on “the pious self-consciousness of the theologizing individual.” 92 Thus they do not base their theology on the objective divine truth, but on subjective human opinions. That has produced the situation so aptly described by Luther in the well-known words which Hase made the motto of his Hutterus Redivivus: “They all have something to sell. Their aim is not to reveal Christ and His mystery, but their own mystery. They think more of that than of the mystery of Christ. Their own beautiful thoughts must not go to waste. Through them they hope to convert even the devils, while they have never yet converted a gnat. And the worst of it is, all they do is pervert the truth.” (St. L. XIV:397.) Naturally, everyone prefers his own brand. And so there is in modern theology no longer any unanimity of doctrine. The moderns do not attempt to hide this situation. Recall the statement of Nitzsch-Stephan: The unanimity in the acceptance of the principle that the Christian doctrine must not be taken from the Bible but out of the pious self-consciousness is accompanied by “uncounted divergencies” of theological trends (Lehrbuch, pp. 16 and IX). Nor does modern theology deplore the chaotic condition that has resulted from the repudiation of the Scripture principle. It has sunk so far below the Christian level that it prizes “the divergent trends” in theology as embellishments of the Christian Church and brands the agreement in doctrine and faith, which Scripture clearly demands,93 as an abnormality, as a “repristination” of an outmoded theological position.

The Erlangen professor Hofmann, of the “conservative” school, has been a most zealous exponent of the Ego theology. In fact, he has been called by some the father of the Ego theology in the Lutheran Church of the nineteenth century. The Leipzig Theologisches Literaturblatt, edited by Ihmels, said in its issue of Dec. 8, 1922: “Hofmann, and still more Frank, have come out squarely for the principle of the ‘self-assurance of Christianity and its theology’ as the all-sufficient source of religious knowledge.” Hofmann tells the theologian that in studying and presenting the Christian doctrine he must, for the time being, completely ignore not only what the Church has taught, but also what the teaching of Scripture is; he must train the theological Ego to form its doctrinal conclusions “in exclusive independence.” We quote from his Schriftbeweis (2d ed., I, 11): “After God has established relations with a man [in Christ], the believer is on his own; that is to say, that after he has been brought into communion with God — and only within the Church, which has the Scriptures, can this be effected — his relationship with God no longer depends on the Church nor on Scripture, to which the Church appeals; it does not look to the Church nor to Scripture for the primary and real confirmation of its truth, but it rests in itself and has an immediate assurance of the truth. The Ego has within itself the Spirit of God to certify the truth. Accordingly, in giving expression to the truth the Ego must remain the only source. Let it speak for itself, unaffected and undisturbed by anything whatever that lies outside itself, that is, outside ourselves. And though that which is outside us stands in close relation, yea, in a causal relation to that which is within us, and though it proves to be the very same truth: nevertheless, that which is within us must be permitted to perform its function in exclusive independence. To be sure, under normal conditions that which Scripture and the Church offers will be the same as what we have found in ourselves. And it is our business to show this agreement. However, that only follows after the performance of our chief task.”

These last statements of Hofmann seem to indicate that he is willing to revise the product of the Ego according to Scripture as the final norm. For that he has been charged with inconsistency, as having abandoned the Ego principle and reverted to “Biblicism” and “intellectualism.” Just recently Horst-Stephan censured Hofmann for adding a “Scripture proof — Schriftbeweis,” “thereby destroying the uniformity of the dogmatic method and returning, in fact, to Biblicistic and Confessionalist dogmatics.” 94 There is something in this charge of inconsistency. Hofmann cannot make Scripture a norm if he would remain true to the principles of his experience theology. Hofmann denies very emphatically that the Holy Scriptures are by inspiration God’s infallible Word. He insists that it is the business of the theologian to separate the truth from the error in Scripture. In that case Scripture cannot remain the norm; it has become a norma normata, which the Ego of the theologian has censored and corrected. If Hofmann really did subject the findings of his Ego to the test of Scripture, if his book really was a “Schriftbeweis,” he was inconsistent.

However, he did not do that. He did not let Scriptures revise, censor, and correct what his theological Ego, working “in exclusive independence” of Scripture, had found to be the true doctrine. On the contrary, he defended even such products of his Ego as the denial of the satisfactio vicaria with the zeal of the fanatic, defended them in spite of the warnings of his friends, defended them as “the enraged lioness protects her cub.” Hofmann was consistent.

He could not pursue a different course. It is impossible to separate these two functions of Scripture: to be the source of the Christian doctrine and to be its norm. The Holy Scriptures are the norm of the Christian doctrine only because they are its only source. And anybody who is in the abnormal state that, in looking for the truth, he compels himself to ignore the Bible completely for the time being and to look exclusively into his own Ego will hardly turn to the Bible later on and ask it to function as the norm and corrective of his Ego product.

Every theologian should be able to see that we are here confronted with an aut-aut. Either we accept Scripture as God’s own Word and, emphasizing it as the sole source and norm of theology, teach doctrinam divinam, or we deny that Scripture is God’s infallible Word, distinguish in it between truth and error, and teach, in God’s Church, the “visions of our own heart,” the doctrina humana of our Ego. The divine authority which we take away from Scripture we necessarily assign to our own human mind. We are adrift on the sea of subjectivism. Human opinion occupies the rostrum in the Church. Theology is no longer theocentric, but has become anthropocentric.

The moderns are determined to establish their anthropocentric theology in the Church — not content with defending it (claiming, e. g., that they are teaching “the old truth” in “a new way”), they launch vicious attacks against those who insist on taking the Christian doctrine from Scripture, on teaching the doctrina divina; they denounce the absolute dependence on Scripture as “intellectualism,” “Biblicism,” “Buchstabentheologie,” “mechanical treatment of Scripture,” treating it as “a manual of dogmatic statutes,” “a codex of laws fallen from heaven,” “a paper pope,” etc. They cannot find invectives enough to apply to the theocentric theology. They employ just about the same abusive vocabulary as the Romanists and the Reformed “enthusiasts” hurled against Luther and the Lutheran Church. Romish theologians have ridiculed the idea as though the Church gets its doctrine from “paper” and “parchment.” 95 They did that in the interest of the principle that the Ego of the Pope is the source and norm of Christian doctrine. The Reformed “enthusiasts,” in like manner, berated Luther’s firm adherence to the Word of Scripture as dead Buchstabentheologie (literalism) and unevangelical Christianity. Their aim was to clear the way for that “Holy Spirit” who does not need a “vehicle” (vehiculum, plaustrum) and finds the use of it beneath His dignity.96 But since it is the way of God’s Holy Spirit to use a “vehicle,” namely, the means of grace, they were in reality — whether they were conscious of it or not — enthroning in God’s Church their own spirit, which was supposed to deal with the Holy Ghost immediately. And that exactly is the aim of the moderns. When they designate the use of Scripture as the sole source and norm of the Christian doctrine as intellectualism, Buchstabentheologie, etc., speak of a “paper pope,” and make the “experience” of the theologian the source and norm of doctrine in place of Scripture, they are actually — whether they are doing it consciously or unconsciously or semiconsciously — setting up the product of their own spirit as the supreme authority in God’s Church. The divine authority which is taken away from Scripture is actually awarded to the Ego of the theologian. The severe words which Luther uses to characterize the animus back of the papistical discrediting of Scripture: “They speak such things only in order to lead us away from Scripture and make themselves masters over us that we should believe their dream sermons (Traumpredigten)” (St. L. V:334), apply in their full force to the moderns. So also what Luther wrote against the Reformed “enthusiasts,” who set the judgments of their own “spirit” against Scripture: “Because of their conceited notion that one must disregard these words, “This is My body,’ and first study the matter spiritually, they presume to correct the Evangelists…. This devil goes about without a mask and openly instructs us to disregard Scripture,97 just as Muenzer and Carlstadt also did; they, too, got their wisdom from the witness of their own heart (“Inwendigkeit”); they did not need Holy Scripture for themselves but for others, merely using Scripture as an external witness of the witness in their heart.” (St. L. XX:1022 f.)

This rejection of the Scripture principle is quite general today. The Ego theology has a monopoly on the modern theological market. The outspoken liberal theologians are not the only ones who sell it. There are many “conservative,” “positive” theologians, too, who do not want to take the Christian doctrine directly from Scripture; that would be, they say, “intellectualism.” Ihmels, for instance, charges that the Early Church and the Church of the Reformation, particularly the dogmaticians, made this mistake. There was, indeed, Ihmels says, some excuse for that. The Early Church had to deal with men “of a religious disposition,” and it was but natural that its “immature theology” would appeal to a special supernatural revelation — meaning the appeal to the Word of the Prophets and Apostles as God’s Word and doctrine. But it was a mistake to employ this “essentially intellectualistic” method. The Church of the Reformation was in a similar situation. Its opponent, the Church of Rome, claimed divine authority for its traditionally accepted teaching, and the Church of the Reformation “calculated that it could establish the truth of its doctrine most effectively by supporting it, in the most direct way, with the authority of divine revelation.” The same wrong method, declares Ihmels, the same intellectualism! Like the Early Church, “the spirit of the Reformation and especially of later Lutheran dogmatics was in the main satisfied with an intellectualistic understanding of revelation.” (Zentralfragen, 2d ed., p. 56 ff.) According to Ihmels, therefore, one must not take the Christian doctrine solely and exclusively from Scripture, for such an intellectualistic use of Scripture (Biblicism) can produce only a dead Christianity, a Christianity of the intellect.

One wonders how the modern theologians get the strange notion that adherence to the Scripture principle necessarily results in intellectualism, dead orthodoxy, lacking inner warmth. And what they offer as proof for their thesis only increases our wonder. They argue that the old method violates the laws of psychology; it fails to establish the “psychological contact.” Richard Rothe describes the situation, as he sees it thus: “The old dogmatics was wrong in assuming that when God gave His revelation, He at once communicated the supernatural truths. This compelled it to conceive of this communication as a mechanical infusion of such truths and this infusion would necessarily be a magic affair, since the psychological contact with man would be missing.” 98 That certainly would be a bad situation. The truth of the matter, however, is that the premise of our old dogmaticians did not compel them to draw Rothe’s deduction, nor did they ever operate with the idea of a mechanical transmission of the superbe natural truths. What they said about the “psychological contact” is exactly the same as what the Apostle Paul said about it. He says in 1 Corinthians 2 that when men “declare the testimony of God,” the Holy Ghost is present and psychologically active, that is, the Holy Ghost, by creating faith, moves the psyche, the hearts of the hearers, to accept the testimony of God. And that is exactly what Quenstedt, as spokesman for the old dogmatics, teaches: “The Gospel of Christ is attested as the truth through the testimony of the Holy Spirit in our hearts. In this manner the Holy Ghost bears witness that His doctrine is the truth, that He, through the doctrine revealed by Him in Scripture, inwardly works so that they accept and believe this doctrine as coming from God, as truly divine doctrine.” (Systema, 1715, I, 145.) Rest at ease; the old dogmaticians and St. Paul did not neglect the matter of the “psychological contact”; everything is in good psychological order.

And let us add that the only way of transmitting the supernatural truths to man is through this creation of a new psychology in him. There is nothing in the psychology of the natural man that will respond to these truths. The Gospel of Christ Crucified has never “entered into the heart of man” (1 Cor. 2:9; Rom. 16:25). And worse, it is to every natural man a “stumbling block” and “foolishness” (1 Cor. 1:23; 2:14). The arguments supplied by the science of apologetics — and there is a great wealth of them — cannot change the human heart, cannot produce an inner acceptance of the Gospel. Accordingly, St. Paul refused to employ the “psychological contact point” of “enticing words of man’s wisdom” ( ); he simply preached the Gospel — with its “demonstration of the Spirit and of power” — in order “that your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God” (1 Cor. 2:5).

); he simply preached the Gospel — with its “demonstration of the Spirit and of power” — in order “that your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God” (1 Cor. 2:5).

It is certainly a strange aberration to hold that teaching the divine truths directly from Scripture produces mere historical faith, merely an intellectual apprehension, and involves a “mechanical infusion of supernatural truths.” — Note, in passing, the conceit of the Ego theology. Most men will agree with us when we say: If the written Word of the Apostles and Prophets of Christ cannot win the hearts of men, cannot establish the “psychological contact,” much less will that word do it which modern theologians have evolved out of their “experience.” Let the Ego theologians study the forceful words which Luther (in the Smalcald Articles) addressed to all “enthusiasts”: “All this is the old devil and old serpent, who also converted Adam and Eve into ‘enthusiasts,’ and led them from the outward Word of God to spiritualizing and self-conceit, and nevertheless he accomplished this through outward words. Just as also our ‘enthusiasts’ [at the present day] condemn the outward Word, and nevertheless they themselves are not silent, but they fill the world with their pratings and writings, as though, indeed, the Spirit would not come through the writings and spoken Word of the Apostles, but [first] through their writings and words He must come” Trigl., 495, 5-6).

That is a bad case of self-deception. And it is not an isolated phenomenon. The entire terminology of the theologians who would procure the Christian doctrine from their own heart moves in the sphere of self-deception, and that means in the sphere of untruthfulness. An examination of the pertinent vocabulary will expose the deception lurking in these phrases. And it is certainly imperative that the theological students of the present age be in a position to detect it.

a. It is sheer delusion to make the Christian “experience” take the place of Scripture. It is a delusion, because without Scripture there can be no Christian experience. Needless to say, there is a Christian experience. Without the personal Christian experience there can be no Christianity. Everyone who is a Christian has experienced, and daily experiences, both sin and grace. He knows and realizes that on account of his sin he is subject to eternal damnation. And he knows and realizes that on account of Christ’s satisfactio vicaria his sins are forgiven. But this twofold experience of the Christian is wrought solely through the preaching and teaching of God’s Word, of the Law and of the Gospel — certainly not through his experience. In order to create this experience of repentance and of the forgiveness of sins, Christ commands that repentance ( ) and remission of sins (

) and remission of sins ( ) be preached in His name among all nations (Luke 24:46 f.), and Paul, by Christ’s command, proclaimed to Jews and Gentiles “that they should repent and turn to God” (

) be preached in His name among all nations (Luke 24:46 f.), and Paul, by Christ’s command, proclaimed to Jews and Gentiles “that they should repent and turn to God” ( , Acts 26:20). This Word, the Word of the Law and the Word of the Gospel, the Church has in the recorded Word of the Apostles, and when the Church preaches this Word, which is God’s own Word and pronounces God’s own verdict in re “sin” and “forgiveness of sins,” men learn to know what repentance (contritio) and forgiveness of sins (remissio peccatorum sive fides in Christum) is. The ideas of sin and salvation which the “grandfather” and the “father” of the Ego theology of the 19th century, Schleiermacher and Hofmann, evolved out of their own heart will never cause a man to experience contritio and fides, fides in Christum crucifixum. As for Schleiermacher, it is quite generally admitted that his Reformed-pantheistic theology ignores the concept of sin completely. And when Hofmann, guided by his faith consciousness, which operates “independently” of Scripture, denies original sin,99 he, too, is a poor preacher of repentance. Furthermore, both Schleiermacher and Hofmann, drawing upon their Ego, deny the satisfactio vicaria. And such teaching and preaching certainly cannot produce the experience of fides, of faith in the Savior crucified for us.

, Acts 26:20). This Word, the Word of the Law and the Word of the Gospel, the Church has in the recorded Word of the Apostles, and when the Church preaches this Word, which is God’s own Word and pronounces God’s own verdict in re “sin” and “forgiveness of sins,” men learn to know what repentance (contritio) and forgiveness of sins (remissio peccatorum sive fides in Christum) is. The ideas of sin and salvation which the “grandfather” and the “father” of the Ego theology of the 19th century, Schleiermacher and Hofmann, evolved out of their own heart will never cause a man to experience contritio and fides, fides in Christum crucifixum. As for Schleiermacher, it is quite generally admitted that his Reformed-pantheistic theology ignores the concept of sin completely. And when Hofmann, guided by his faith consciousness, which operates “independently” of Scripture, denies original sin,99 he, too, is a poor preacher of repentance. Furthermore, both Schleiermacher and Hofmann, drawing upon their Ego, deny the satisfactio vicaria. And such teaching and preaching certainly cannot produce the experience of fides, of faith in the Savior crucified for us.

In order to bring about contritio, something other than human opinions concerning sin, even though they be “scientifically mediated,” must be taught. God’s Holy Law alone can do it. God’s Law, as the Church has it to the end of time in the written Word of Scripture, must be preached without additions or subtractions. (Matt. 5:17-19; Gal. 3:10, 12.) That, “then, is the thunderbolt of God by which He strikes in a heap [hurls to the ground] both manifest sinners and false saints [hypocrites], and suffers no one to be in the right [declares no one righteous], but drives them all together to terror and despair. This is the hammer, as Jeremiah says, 23:29: ‘Is not My Word like a hammer that breaketh the rock in pieces?’ This is not activa contritio, or manufactured repentance, but passiva contritio [torture of conscience], true sorrow of heart, suffering, and sensation of death. This, then, is what it means to begin true repentance; and here man must hear such a sentence as this: You are all of no account, whether you be manifest sinners or saints [in your own opinion]; you all must become different and do otherwise than you now are and are doing [no matter what sort of people you are], be you as great, wise, powerful, and holy as you may. Here no one is [righteous, holy] godly.” (Smalc. Art., Trigl., 479, 2-3.) Nor will human opinions concerning the forgiveness of sins, even if they be “scientifically mediated,” bring about faith, which must be added to contritio, to the terrores conscientiae. God’s opinion must be taught, God’s Word, which the Church, thanks to God, possesses in the Gospel written down in Scripture. That, then, is God’s Gospel,  , unto which Paul was separated (Rom. 1:1) and which he faithfully proclaimed, suffering neither theologizing men nor an angel from heaven to change it (Gal. 1:7-9). If this Gospel of God is proclaimed and taught in the Church, then we have there, as Luther says, “the consolatory promise of grace through the Gospel” (Smalc. Art., Trigl., 481, 4). Through the Word of the Gospel, faith is produced. The object of faith is the Word of the Gospel, for in the Word of the Gospel it apprehends the forgiveness of sins gained by Christ. Luther: “This is the faith that apprehends Christ, who died for our sins and rose again for our justification. This is the faith which Paul preaches and which the Holy Spirit gives and preserves in the hearts of the believers in order to accept the Gospel.” (Opp. v. a. IV, 486.)

, unto which Paul was separated (Rom. 1:1) and which he faithfully proclaimed, suffering neither theologizing men nor an angel from heaven to change it (Gal. 1:7-9). If this Gospel of God is proclaimed and taught in the Church, then we have there, as Luther says, “the consolatory promise of grace through the Gospel” (Smalc. Art., Trigl., 481, 4). Through the Word of the Gospel, faith is produced. The object of faith is the Word of the Gospel, for in the Word of the Gospel it apprehends the forgiveness of sins gained by Christ. Luther: “This is the faith that apprehends Christ, who died for our sins and rose again for our justification. This is the faith which Paul preaches and which the Holy Spirit gives and preserves in the hearts of the believers in order to accept the Gospel.” (Opp. v. a. IV, 486.)

To repeat, the Christian experience of sin and grace is wrought solely through God’s revelation in His Word, in no way through an immediate operation of God or through God’s operation in the realm of nature and of history. To the extent that men — “laymen” or “theologians” — separate themselves from Holy Scripture as God’s own Word, addressed to us, to that extent they are cut off from the Christian “experience.” Men deny this and assert that God powerfully influences our lives through certain occurrences in nature and certain events in history. We answer that God certainly makes use of these events — makes use of them to direct man’s external attention to the proclamation of the Word of Christ. But that experience of sin and grace whereby man becomes a Christian and remains a Christian is effected only through the teaching of the divine Word, whether Scripture be directly quoted or not. Without the preaching of Christ’s Word darkness covers the earth and gross darkness the people, even though the nations are surrounded by “history,” even though God speaks to them with a loud voice in earthquakes, war, famines, etc.100 For this reason the Church of Christ must continue her mission work among all nations, to the ends of the earth, to the end of time, no matter what and how much is happening among them in history and in the realm of nature. For “how shall they believe in Him of whom they have not heard? … So, then, faith cometh by hearing, and hearing by the Word of God. (Rom. 10:14, 17.)

b. Again, the modern theologians are dealing with a delusion when they refuse to derive the Christian doctrine from Scripture but make “faith” or the Christian “faith consciousness” supply it. Not only the radical but also the conservative modern theologians are doing that.101 To be sure, there is a Christian faith consciousness, and out of it the Christians speak and teach. “I believed, and therefore have I spoken” (2 Cor. 4:13; Ps. 116:10). But this Christian faith has its being exclusively in the Word of the Apostles (John 17:20). The Christian faith knows nothing but God’s Word. That “faith,” however, which is not faith in the Word of the Apostles, which declares its independence of the Word, rejecting it as the sole source and norm of faith, is ex toto, in every respect, human delusion; as Paul puts it (1 Tim. 6:3), the teaching of those who do not abide by the wholesome words of Christ proceeds out of conceited ignorance. Luther indeed says: “Faith teaches and holds to the truth,” but he adds at once: “For faith clings to the Scriptures; they do not lie and deceive.” (St. L. XI: 162.) “Faith” and “God’s Word” are certainly inseparably joined together, but not in this wise that faith comes first and doctrine follows, faith making the doctrine, but in this wise that the Word is first and fixes and determines faith. As Luther says: “The Word of God is first, and out of it flows faith.” “Whatever does not have its origin in Scripture is surely of the devil himself.” Because the theologians, says Luther, had gotten away from Scripture, “which alone is the source of all wisdom in theology,” such “monstrosities (portenta)” arose in theology “as Thomas, Scotus, and others.” (St. L. XIX:34; 1080; I:1289 f.) This severe judgment of Luther applies to its full extent to modern theology in so far as it will not permit God’s Word, Holy Scripture, to be faith’s source of knowledge and its object, but wants faith to be its own source and its own object.

Some advocates of the Ego theology have gone even farther. They set up the monstrous proposition that the Christian religion is not “in real truth” concerned with doctrine and hence Scripture must not be regarded as “a divine manual of religion” (Nitzsch-Stephan, p. 249). This notion, they say, is a papistical remnant still clinging to the dogmaticians. And to Luther, too. Also Meusel’s Kirchliches Handlexicon places doctrine and Christian religion in opposition. “What the New Testament, and also St. Paul, is primarily concerned with is not doctrine, but revelation and religion. What Grau (in Zoeckler, Handbuch der Theologischen Wissenschaft, I, 561) says concerning Paulinism — that its tenor is religion and life, not dogma or system of doctrine — holds true of the entire New Testament.” (IV, 209, sub Lehrbegriff.) This view, though unscriptural and unreasonable, is shared also by Ihmels. He makes statements like this: “The essential thing about revelation is not that it imparts doctrine, but that it is a self-disclosure of God. Clearly only such an understanding of revelation is in accord with evangelical faith.”102 But Christ’s Word, which we have in the Word of His Apostles, is exactly that: in it God both manifests Himself and imparts the doctrine, the doctrine on which alone the faith that knows the truth is based. Christ states distinctly: “If ye continue in My Word ( ) … ye shall know the truth.”

) … ye shall know the truth.”

Depriving faith of its object, namely, the doctrine presented in Scripture, has, as Eduard Koenig said, fatal results: It destroys the Biblical concept of “believing” and does away with the Christian religion as a positive religion.103 Indeed, it is due to an astounding aberration of the human mind that men can assert that “doctrine” or the “communication of doctrine” is not a “prime” concern of the Christian religion; we cannot comprehend how they can claim in all seriousness that what is to be preached is not “doctrine,” but “faith,” arguing that only in this way “a living Christianity can be produced” and “dead orthodoxy,” “intellectualism,” warded off. The stubborn fact is that from its very beginning the Christian religion dealt with doctrine and the impartation of doctrine. The Word spoken in the very beginning about the Seed of the woman, who would crush the head of the Serpent (Gen. 3:15), what is it but doctrine? And the entire Old Testament was written, as the Apostle Paul assures us, for our learning,  (doctrine), Rom. 15:4, and is profitable

(doctrine), Rom. 15:4, and is profitable  (doctrine), 2 Tim. 3:16. When in the fullness of the time the Son of God appeared in the flesh and walked here on earth, He engaged in teaching. He teaches from the ship (Luke 5:3), on the mount (Matt. 5:2), in the synagogs (Luke 4:15), went about the land teaching (Matt. 4:23). He also makes use of the forty days between His resurrection and ascension to teach (Acts 1:3), and before His ascension He gives His Church the commission to teach all nations to the Last Day: “Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:20). And the Apostles executed this commission. Paul declared, taught, publicly and from house to house, all the counsel of God (Acts 20:20, 27). Teaching the saving doctrine was his chief business, and he tells his successors in the ministry that it must be their chief business. He bids Timothy and Titus to hold fast the form of sound words, the doctrine, which they had heard from him (2 Tim. 1:13; Titus 1:9; 2 Tim. 2:2) and requires of the bishop that he should be apt to teach,

(doctrine), 2 Tim. 3:16. When in the fullness of the time the Son of God appeared in the flesh and walked here on earth, He engaged in teaching. He teaches from the ship (Luke 5:3), on the mount (Matt. 5:2), in the synagogs (Luke 4:15), went about the land teaching (Matt. 4:23). He also makes use of the forty days between His resurrection and ascension to teach (Acts 1:3), and before His ascension He gives His Church the commission to teach all nations to the Last Day: “Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:20). And the Apostles executed this commission. Paul declared, taught, publicly and from house to house, all the counsel of God (Acts 20:20, 27). Teaching the saving doctrine was his chief business, and he tells his successors in the ministry that it must be their chief business. He bids Timothy and Titus to hold fast the form of sound words, the doctrine, which they had heard from him (2 Tim. 1:13; Titus 1:9; 2 Tim. 2:2) and requires of the bishop that he should be apt to teach,  (1 Tim. 3:2). Teachers should know that Scripture is given first of all “for doctrine” (2 Tim. 3:16). The members of the congregations, too, are bidden, like the teachers, to continue in the doctrine and to apply the doctrine to one another. Col. 3:16: “Let the Word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom, teaching and admonishing one another.” 2 Thess. 2:15: “Therefore, brethren, stand fast, and hold the traditions which ye have been taught, whether by word or our Epistle.” It is said in praise of the Christians at Jerusalem that they continued steadfastly in the Apostles’ doctrine,

(1 Tim. 3:2). Teachers should know that Scripture is given first of all “for doctrine” (2 Tim. 3:16). The members of the congregations, too, are bidden, like the teachers, to continue in the doctrine and to apply the doctrine to one another. Col. 3:16: “Let the Word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom, teaching and admonishing one another.” 2 Thess. 2:15: “Therefore, brethren, stand fast, and hold the traditions which ye have been taught, whether by word or our Epistle.” It is said in praise of the Christians at Jerusalem that they continued steadfastly in the Apostles’ doctrine,  (Acts 2:42); and the Apostle John deems the adherence to the doctrine of Christ of such great importance that he instructs the churches to deny Christian fellowship to all who do not bring the doctrine of Christ (2 John 9-11). When in spite of all this modern theologians insist that Holy Scripture must not be regarded as “doctrine” nor received as a “manual” of the Christian religion, it is evident that their conception of the Christian religion is diametrically opposed to that of Christ and His Apostles and Prophets.

(Acts 2:42); and the Apostle John deems the adherence to the doctrine of Christ of such great importance that he instructs the churches to deny Christian fellowship to all who do not bring the doctrine of Christ (2 John 9-11). When in spite of all this modern theologians insist that Holy Scripture must not be regarded as “doctrine” nor received as a “manual” of the Christian religion, it is evident that their conception of the Christian religion is diametrically opposed to that of Christ and His Apostles and Prophets.

c. The moderns are deluding themselves when they imagine that the “regenerate Ego” or the new man in the theologian can and will serve as the source of Christian doctrine. Surely, the regenerate Ego, the new man, speaks and teaches. And it is the will of God that all teachers of the Church should be reborn, new men (see chap. 9). But you are insulting the new man if you consider him capable of committing the folly of disregarding Scripture, even though only “for the first,” and seeking some other source and norm of the Christian doctrine. Where this method is employed, the old Adam is playing the theologian. There the revolutionist is at work, breaking down the foundation on which the Christian Church is built (Eph. 2:20). There Nietzsche’s “Superman” has taken over. Nietzsche placed his Ego above God’s Moral Law, “beyond good and evil”; even so the moderns place themselves as “supermen” above God’s Word by asserting that it is for the theologian to determine what is true and what is false in Scripture and that only so much of Scripture is true as has approved itself as the truth to the theologian’s Ego, his “experience,” etc. The new man, however, does not engage in that kind of theology. The new man in the theologian has too much sense for that. He knows Scripture to be the Word of God, subjects himself to it unconditionally, regulates and forms his thoughts and judgments according to the “It is written,” and with Luther submerges all thoughts that emerge in his old Adam contrary to Scripture. The new man has learned from John 8:31-32 that only by continuing in Christ’s Word can the truth be known, and he is therefore guided by the general rule binding all teachers: “If any man speak [that is, in the Christian Church], let him speak as the oracles of God” (1 Pet. 4:11).

We are not impugning the personal faith of everyone who is enmeshed in the Ego theology. Here, too, a “felicitous inconsistency” may obtain. It will happen, too, that one and the same theologian contradicts himself in one and the same writing; on the one hand he declines to base his faith on “doctrines communicated” in Scripture, and on the other hand he practically admits that faith without the Scripture basis is not faith but delusion. A Christian theologian may forget for a time what the true situation is; but when his Christian intelligence asserts itself, his new man clearly sees that it is a trick of the old man to play up the “regenerate Ego” and “faith” and “faith consciousness” against the Word of Scripture, the only source and norm of theology.

d. It is hard to understand how men can make themselves believe that in ascertaining the Christian doctrine one must look not so much to the words (usually they say “the letter”) of Scripture as rather to the “content,” the import. Here we have one of the many catch phrases which despite their inanity endure from generation to generation. It is a formula which requires us to perform a logical and psychological impossibility. You cannot understand the content of a message without the words which express that message. And since the meaning of Scripture like that of any other writing, lies solely in the words of Scripture, this meaning is certain only because the words are certain and reliable. If we cannot rely on the words of Scripture, the doctrinal content of Scripture will ever remain a matter of conjecture and doubt. But in order to save us from this condition of uncertainty, which to the anxious soul is more bitter than death (cp. Trigl., 291, 31), the Savior assures us that Scripture cannot be broken and directs us to the words of His Apostles. The instruction given John 8 does not say: “If ye continue in the content of My Word,” but “If ye continue in My Word ( ), then … ye shall know the truth.” So also the instruction Christ gives in John 17:20 does not separate content and words, but declares that men will believe in Him through the word of the Apostles (

), then … ye shall know the truth.” So also the instruction Christ gives in John 17:20 does not separate content and words, but declares that men will believe in Him through the word of the Apostles ( ). —This matter will be taken up again in the locus “Holy Scripture,” particularly in the chapter on the “variae lectiones,” which some adduce as disproving the trustworthiness of the Word of Scripture.

). —This matter will be taken up again in the locus “Holy Scripture,” particularly in the chapter on the “variae lectiones,” which some adduce as disproving the trustworthiness of the Word of Scripture.

Take note that also the Christian experience (Erlebnis) protests most emphatically against this proposed separation of the contents and the words of Holy Scripture. In the seclusion of his study the theologian may be satisfied to say: “Not the words but the contents of Scripture is what counts.” He will not say it when his soul is battling for its life. Consciences stricken by the Law of God can find peace only when they take their stand on the unshakable foundation on which the whole Christian Church is built, on the Word of the Apostles and Prophets (Eph. 2:20), on Christ’s own Word (John 8:31). Lessing, indeed, cried out: “Who will deliver us from the intolerable yoke of the letter!” (meaning the words of Scripture), and modern theology, separating the import of Scripture and the words of Scripture, fulfilled his wish. But remember, Lessing preferred a state of doubt to the state of certainty; as witness his well-known declaration: “If God held in His right hand all truth and in His left only the ever-active impulse to search for truth, even with the condition that I must always make mistakes, and said to me: ‘Choose!’ I should humbly bow before His left hand and say: ‘Father, give me this. Pure truth belongs to Thee alone.’”104 That is in accord with Lessing’s religious position, his “experience.” “Lessing did not treat the concepts ‘sin’ and ‘redemption’ as matters concerning him personally; as a consequence a supernatural revelation, the Word of Scripture, had no value for him.”105

e. The contention, finally, that because of the “historical character” of the Christian religion the philosophy of history must determine the Christian doctrine is not in accord with the facts of history.106 To be sure, the Christian religion bears a “historical character,” and pre-eminently so. Scripture testifies that the eternal Son of God became man and thus entered “history.” The Eternal became temporal. Scripture furthermore tells us that this wonderful divine mystery was revealed by the command of the eternal God, through the prophetic writings, in human language and thus became a part of recorded history. “According to the revelation of the mystery … now made known to all nations” (Rom. 16:25 f.). And here is another historical fact with which the philosophy of history must deal: “the revelation of salvation” has been completed with the Word of Christ, which we have in the Word of His Apostles. It is so fully finished and closed that all subsequent history cannot change it in the least. Richard Gruetzmacher is perfectly right in saying: “For us the historical revelation of salvation is contained solely in the record of it given in Holy Scripture.” 107 Now, the position of the moderns is not in accord with this historical fact. When they operate with the “historical character” of Christianity for the purpose of setting aside Scripture as the only source and norm of the Christian doctrine from their own cogitations, they are engaged in an entirely unhistorical attack on the true history of Christianity. They are simply deluding themselves with their talk about evaluating Christianity “historically.” Moreover, by making the “philosophy of history” a source and norm of the Christian doctrine, they are infringing on the authority of Christ: Christ in His Word is the one and only Teacher ( ) in the Church to the end of days (Matt. 23:8; 28:19-20; John 8:31-32; 17:20).

) in the Church to the end of days (Matt. 23:8; 28:19-20; John 8:31-32; 17:20).

To sum up: If we, the theological teachers, refuse to recognize Scripture as God’s own Word and to employ it as the sole source and norm of theology, we shall not be teaching God’s doctrine (doctrinam divinam), but our own opinions (proprias opiniones). It is immaterial whether we call this subjective source and norm Christian experience or faith or faith consciousness or the regenerate Ego or the historical understanding of Christianity, etc. All roads that by-pass Scripture as the one and only source and norm of theology lead into the Ego theology. And we, as Christians, should remind ourselves of the words of Luther, already quoted: “They speak such things only in order to lead us away from Scripture and make themselves masters over us, that we should believe their dream sermons (Traumpredigten)” (St. L. V:334). Employing drastic language, Luther says (col. 336): “They would lead us away from Scripture, obscure faith, lay and hatch their own eggs, and become our idol.”

The situation, then, is this: Modern theology must execute a complete change of base before it can claim to be Christian theology. It must abandon its basic principle that Scripture is a human book and must learn again to “identify” Scripture and the Word of God. It must recognize the claim of Scripture that it is God’s own infallible Word. It must declare with Christ and His Apostles: “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God” (2 Tim. 3:15, 16); “The Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35); “It is written” (Matt. 4:4, 7, 10). (See also Luke 24:25; John 17:12; Matt. 26:54; Rom. 16:25-26; 2 Thess.2:15.) It will then have learned the only correct theological method, the method according to which we refuse to draw the Christian doctrine either out of the Ego of other men or out of our own Ego but accept Scripture unreservedly as the “divine manual of religion” and stand squarely on the proposition: Quod non est biblicum, non est theologicum. Then, too, there will be an end to the nasty talk about Buchstabentheologie, intellectualism, Biblicism, paper pope, codex of dogmas fallen from the skies, etc. No, we have learned and joyfully proclaim that the doctrine taken from Scripture, being God’s own doctrine, doctrina divina, has the benign power to win its way into the hearts of men and that, far from inducing “dead orthodoxy,” it produces “living” Christianity, Christianity pulsating with divine warmth and strength. Likewise the multiform gibes about “pure doctrine” will disappear; coming under the rule of the Scripture principle, men no longer ridicule “the sound doctrine” ( , Titus 1:9; 2 Tim. 1:13), but realize with holy fear that this is the only kind of doctrine permissible in God’s Church, the only kind befitting the Christian teacher.

, Titus 1:9; 2 Tim. 1:13), but realize with holy fear that this is the only kind of doctrine permissible in God’s Church, the only kind befitting the Christian teacher.

The conviction that Holy Scripture is God’s own Word and the sole source of the divine doctrine, produces these three chief virtues in the theologian: (1) He will despair of his wisdom and approach Scripture with the humble spirit that prays: “Speak, Lord; for thy servant heareth” (1 Sam. 3:9). (2) He will not seek other textbooks of the Christian doctrine, but will receive the doctrine revealed in Scripture by faith, the only medium cognoscendi of the divine doctrine, and faithfully teach it; he will pray God to keep him from mixing the chaff of his own foolish thoughts with the wheat of the divine thoughts (Jer. 23:28). (3) He will through the grace of God have the courage and strength to demand exclusive authority for the doctrine taken from Scripture as being God’s own doctrine and thus do his part to check the ravages of indifferentism, doctrinal chaos, and confusion. — Theodore Kaftan has been charging certain men whom he classes with the “old theologians” with a “deficiency in confidence and strength.” He says: “It is very noticeable that the attitude of these representatives of the old theology, taken as a whole, is that of despondency; a sort of discouragement, a feeling of weakness frequently prevails; they say, in effect: We are a failure.” 108 If these old-school theologians have indeed, as Kaftan asserts, become disheartened and weak-spirited, it is only because the pressure of the Zeitgeist has shaken their conviction that Scripture is by inspiration God’s own infallible Word. But as soon as these men become aware of the real situation and again realize on what their faith and the faith of all Christendom is founded (Eph. 2:20) and what they absolutely need in their temptation from within and without, they will again with Christ and His Apostles confidently utter the  , “It is written,” and repeat, not merely with the mouth, but from the depth of their hearts, the word of Luther: “Das Wort sie sollen lassen stahn.” They will then also know how to appraise the “greater confidence” which Kaftan finds in himself and other modern theologians; it is the “confidence” of men who are “puffed up with conceit” (1 Tim. 6:4, R. S. V.), the “confidence” of the Pope and the “enthusiasts” of all times. Luther describes it thus: “All confidence which is not based on the Word of God is vain” (St. L. VI:70. on Is. 7:9). “Solely through His Word, God would declare to us His will and His counsels, not through our notions and imaginations” (St. L. III:1417 on Deut. 4:12).

, “It is written,” and repeat, not merely with the mouth, but from the depth of their hearts, the word of Luther: “Das Wort sie sollen lassen stahn.” They will then also know how to appraise the “greater confidence” which Kaftan finds in himself and other modern theologians; it is the “confidence” of men who are “puffed up with conceit” (1 Tim. 6:4, R. S. V.), the “confidence” of the Pope and the “enthusiasts” of all times. Luther describes it thus: “All confidence which is not based on the Word of God is vain” (St. L. VI:70. on Is. 7:9). “Solely through His Word, God would declare to us His will and His counsels, not through our notions and imaginations” (St. L. III:1417 on Deut. 4:12).