_7_Ecclesiastical Terminology and the Christian Knowledge of God

Scripture does not reveal the doctrine of the Trinity as a metaphysical speculation or an academic problem, but as an exceedingly practical article of faith necessary for our salvation. Scripture establishes an indissoluble nexus between the doctrines of the Trinity and soteriology. (Rom. 16:25 f.) In accord with the Holy Scriptures, the Constantinopolitanum presents the doctrine of the Trinity as to its soteriological meaning and import. It not only confesses, “I believe in one God, the Father Almighty; and in one Lord Jesus Christ; and I believe in the Holy Ghost,” but with its confession of the deity of Christ it unites the confession of the saving truth, that the second Person became man and was crucified and died for us; and to its confession of the deity of the Holy Ghost it adds a statement concerning His soteriological work, calling Him “the Life-giver,” and “divine Revealer.” Luther likewise points to the integral unity between the three Persons in God and God’s plan for man’s salvation. He says: “Such revelation (of God’s most inner being, as three Persons in one divine essence) is in accord with God’s highest work and indicates His divine counsel and will, for God has decreed from eternity and accordingly revealed in the many Messianic promises that His Son should become man and die to reconcile lost mankind to God. Nothing could redeem us from the dreadful fall into sin and from eternal death except an eternal Person who has the power to destroy sin and death and to give eternal righteousness and life instead. For this no angel nor any other creature was sufficient. Only God Himself could accomplish this.” (St. L. XII:632.)

Self-righteous and conceited man rejects the doctrine of the Trinity; he has no use for the soteriological import of this revealed doctrine. And man’s enmity is directed primarily against the essential deity of Christ, whom self-righteous and conceited man will not accept as the only Mediator between God and man. The words of 1 Tim. 2:6: “He gave Himself a ransom for all,” are, as Luther says, “nothing but thunderclaps and fire from heaven against the righteousness of the Law and the doctrine of works. The wickedness, error, darkness, ignorance, of my will and intellect was so great that only an inexpressibly great ransom could free me.” (St. L. IX:236 f.)

But the Christians realize the seriousness of the attacks upon the essential deity of Christ. They know that a denial of Christ’s deity destroys the theanthropic work of redemption and thus of the object of saving faith. And the Lord has always raised stanch defenders of the deity of Christ and of the Holy Ghost. He did so in the life-and-death struggle of the Christian Church during the Trinitarian controversies of the third and fourth centuries (Athanasius in 325 at Nicaea; the Cappadocians in 381 at Constantinople). Today the controversy of the Church with Modernism is no less serious and difficult. In the interest of its self-righteousness modern theology has reduced Christianity to an ethical religion; in the interest of the alleged omnicompetence of reason, Modernism has adopted the so-called scientific method in religion. This is an open disavowal of divine revelation, of Christ’s vicarious atonement, and of the Scriptural doctrine of the Trinity. In view of man’s hatred against this doctrine and the persistent attack upon this article, it is, indeed, a miracle of divine grace that the Christian doctrine of the Trinity and with it the Christian knowledge of God and the Church itself have survived. A study of the history of dogma reveals, as Luther points out, that God has guarded this doctrine with special care (St. L. XIII:675). Even a man like Wilhelm Augusti, who struggled valiantly to steer his ship out of the fog of rationalism, wrote: “History introduces us to outspoken opponents as well as to men who attempted to explain and modify the doctrine of the Trinity. But it is a striking phenomenon that from the beginning of the Christian Church down to our day neither the outspoken opponents nor the compromising theologians have been able to suppress this doctrine, confident though they were of their anti-Trinitarian position. Nor has faith in the Trinitarian God ever proved to be an obnoxious error; on the contrary, both in theory and in practice it has proved to be a salutary doctrine. These facts speak louder for the doctrine than all the prating about its incomprehensibility speaks against it.” 41

The ecclesiastical terminology is not of absolute necessity. The terminology employed by the Church during the first five centuries against the opponents of the Trinity is found in the Athanasian Creed, also known as the Quicunque.42 Though many Christians are not acquainted with the terminology, they nevertheless believe and accept the correct doctrine on the basis of clear Scripture passages. An examination of the content of the ecclesiastical terms reveals that they constitute an epitome (Luther: “Summarienwort”) of what Scripture teaches of the Trinity more clearly than the sun (sole clarius). It is therefore desirable that Christians become thoroughly familiar with the Church’s terminology. For this reason our hymnal very properly contains the three Ecumenical Creeds. Luther did not hesitate to employ ecclesiastical terminology in his sermons and to quote, for example, the Athanasian Creed (St. L. X:1007). Modern Unitarians thoroughly despise it, but Luther said: “I doubt whether the New Testament Church has a more important document since the Apostolic Age” (St. L. VI:1576).

Among the terms which the Church has employed in presenting the Christian knowledge of God, the following are the most significant: 1) Trinity; 2) Person; 3) Essence; 4) Homoousia; 5) Filioque; 6) Perichoresis; 7) Opera divina ad intra et ad extra.

1. Trinity. This term does not occur in the Holy Scriptures,43 but summarizes everything which God has revealed in Scripture concerning Himself, namely, that He is one (1 Cor. 8:4) and yet the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost (Matt. 28:19).44 In their rejection of the Church’s Trinitarian formulation, modern theologians have appealed to Luther. But this appeal to Luther’s authority is as invalid as when the same theologians claim Luther as a champion of the denial of Verbal Inspiration. True, Luther said that neither the Latin word trinitas, nor the German Dreifaltigkeit are adequate terms (“lauten nicht koestlich”), but he adds that human language is too limited to express adequately the lofty article of the Trinity; this doctrine so far surpasses human understanding that God as a kind Father will condone stammering and prattling of His children so long as their faith is correct; this term expresses the Church’s faith as well as can be done in human language, for the word Trinity conveys the Christian knowledge of God, namely, that the Divine Majesty is three distinct Persons in one divine essence. (St. L. XII:628 f.)

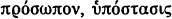

2. The word person (persona,  ) has been and still is being employed by the Christian Church to disavow the Unitarian heresy which considers the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost only three manifestations and modes of operation or three powers and divine attributes. Luther points out that the term person was used by the Early Church to refute the folly of the Monarchian heretics as though the three names could denote one and the same Person in three successive manifestations (St. L. XIII:674). Like the ancient Unitarians, so also our modern Unitarians make fools of themselves when they reduce the three Persons to three powers, operations, and divine attributes. The term person, however, is employed not only antithetically, but also positively, for it clearly sets forth that in the one God there are three individual personal agents (“Ich”), or self-subsisting subjects (“Selbstaendige”). Luther: “Because Christ is born of the Father, He must be a Person distinct from the Father. You may use whatever term you will, we use the term person. We realize, of course, that our terminology is inadequate and is really only a stammering. But we cannot do justice to this truth, for we have no better term.” (St. L. XIII:669.) The definition of the Augsburg Confession is fully satisfactory. “And the term person they use as the Fathers have used it, to signify, not a part or quality in another, but that which subsists of itself.”45

) has been and still is being employed by the Christian Church to disavow the Unitarian heresy which considers the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost only three manifestations and modes of operation or three powers and divine attributes. Luther points out that the term person was used by the Early Church to refute the folly of the Monarchian heretics as though the three names could denote one and the same Person in three successive manifestations (St. L. XIII:674). Like the ancient Unitarians, so also our modern Unitarians make fools of themselves when they reduce the three Persons to three powers, operations, and divine attributes. The term person, however, is employed not only antithetically, but also positively, for it clearly sets forth that in the one God there are three individual personal agents (“Ich”), or self-subsisting subjects (“Selbstaendige”). Luther: “Because Christ is born of the Father, He must be a Person distinct from the Father. You may use whatever term you will, we use the term person. We realize, of course, that our terminology is inadequate and is really only a stammering. But we cannot do justice to this truth, for we have no better term.” (St. L. XIII:669.) The definition of the Augsburg Confession is fully satisfactory. “And the term person they use as the Fathers have used it, to signify, not a part or quality in another, but that which subsists of itself.”45

Modern theologians of the so-called conservative wing claim that the concept person has changed in the course of the centuries. Seeberg states: “At one time the word person denoted an individual being; today, however, this term designates the soul-life [“das geistige Wesen”] of an individual being.” 46 Even Ihmels says that the term person when applied to the inter-Trinitarian life of God dare not be understood in the sense of an individual personality.47 But the term person as a designation of the inter-Trinitarian relation, or “internal essence,” has not undergone and will never undergo a change, because God and His Word can never change. As was shown above, every Christian believes on the basis of the Holy Scriptures that God is three Persons, three distinct Persons, and the concept of person has not changed. But today we are confronted by a “theology” which follows the strange method of seeking God not in His Word, but in the subjective experience of the theologian. These modern theologians have changed the terms Father, Son, and Holy Ghost to denote three divine energies, operations, and wills. Seeberg: “The eternal dynamic love of God filled the human soul of Jesus, and this constitutes its essence. In this the deity of Christ consists.” (Loc. cit.) But this is really nothing new. We find that the Dynamic Monarchians of the third century attempted to transform the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost into mere powers. By God’s grace, however, the Church of the 20th century will abide by that definition of the word person which is clearly taught in Holy Scripture. In bold defiance of every type of Unitarianism, we declare with Luther: “This article of the Holy Trinity has been maintained, first, with the Word of God; then, through the valiant stand of the Apostles and the Church Fathers; and, finally, with miracles against the devil and the world. And with God’s help this doctrine shall be maintained.” (St. L. XIII:679.)

But while Luther and the dogmaticians with the ancient Church Fathers retain the term person — because they have no better term — they do not fail to point out the unique usus loquendi of the word in this doctrine. Ordinarily three persons have three essences, three wills, three distinct operations. But in the Trinity the three Persons have one and the same essence, not three; one set of divine attributes, not three; one operation in divine works (ad extra), not three. Three human persons are said to have one essence, but only in kind (secundum speciem); the three Persons in the Trinity have one essence in number (secundum numerum, eandem numero essentiam). For this reason the doctrine of the Trinity is an inscrutable mystery. Hence human reason also cannot comprehend how only the Second Person became man without the Father and the Holy Ghost at the same time becoming man. The fact is clearly stated in Holy Scripture (John 1:14; Gal. 4:4; Col. 2:9); the manner surpasses all human comprehension. Luther: “I would presume to be as sagacious as any heretic if I would interpret the words ‘the Word was made flesh’ to suit my whim and fancy” (St. L. VII:2161). Chemnitz says in his Loci concerning the use of the term person in the doctrine of God: “The use of the term person differs from the ordinary usus loquendi. We know what the word person signifies among men or among angels. Peter, Paul, and John are three persons, who, while they have the one human nature in common, differ in many respects: personality, age, will (Gal. 2:11); influence (1 Cor. 15:10); fields of labor (Gal. 2:8). In the Trinity, however, the three Persons cannot be distinguished as one angel is distinguished from another, one human being from another. The entire Peter, for example, is separated locally from the entire Paul. Christ, however, says, ‘I am in the Father, and the Father in Me’ (John 14:10). While men have a common nature, it does not follow that all the other persons are where the one person is (cp. Dan. 10:13). The Son, however, says: ‘He that sent Me is with Me’; the Father hath not left Me alone (John 8:29). Among men and angels the individual persons differ from one another regarding time, will, power, activity. Among the Persons of the Trinity, however, there is coeternity, one will, one power, one activity. This distinction must be observed. This mystery would not be so great if the one essence were three persons, as Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, are three persons who have in common the angelic nature. On the basis of these fundamental facts, the rule has been established: the Persons of the Trinity are different, not essentially, as in creatures, where each has its own peculiarity (suum proprium esse), nor is the distinction only notional, as Sabellius held, but there is a real distinction, though the manner is incomprehensible and unknown to us. If anyone raises the objection that the terms essence and person are not sufficiently restrictive to express the mystery of the unity in the Trinity, then we may answer with Augustine: ‘Human language labors under a truly great paucity of words. We speak of three persons not in order to say just that, but rather so as not to be silent altogether (De Trin. V).’ ”

3. Essence. Essentia,  . The term essence, like person, has singular meaning when used in the doctrine of the Trinity. It denotes the one divine essence which in its totality and without any division is the property of each of the three Persons. We sometimes say that three persons have the same essence. This is correct if we use the term as a universal proposition, an intellectual abstraction, or a philosophical (nominalistic) concept, to denote a characteristic which is common to everyone in an entire class or genus. This definition, however, does not apply to the doctrine of the Trinity. The one divine essence of the three Persons is a true reality, because there is only one such essence which belongs to each person wholly and without division, in fine, is the true God. This is the doctrine of the teachers of our Church. Chemnitz, for example, points out that while the essence of man is said to be communicable, in reality it is only a universal concept, which does not actually exist per se, but is only inferred in the thought and conceived of by the intellect. The divine essence, however, is communicable, is not an abstract concept, a genus, or a species, but is a true reality. He refers to Augustine’s excellent statement: “Essence is ascribed to the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, but not in the common sense when various species are said to have a common genus, or a number of individuals are said to belong to the same species, or when that which is applied to the whole is applied also to its parts. Essence is ascribed to the three Persons in an ineffable and incomprehensible manner.” Chemnitz reminds us also of Augustine’s splendid rule: “If you cannot find out what God is, beware lest you make Him what He is not.” The Church therefore does not use the term essence in the philosophical meaning of a universal term, but as the truly existing divine nature, which is communicable and is therefore common to all three Persons and is totally and entirely in each Person. Chemnitz concludes: “I do not know what the essence of God is unless we say that the divine attributes are God’s essence itself.” (Loci, I, p. 38 sq.) Gerhard defines the term essence in almost the same words as Chemnitz: “The ‘essence of man’ is a universal term, which does not actually exist per se, but is only inferred in thought and conceived by the intellect. But as used of the Godhead, essence is not an imaginary something, as genus or species, but actually exists, though it is communicable” (Loci, locus “De Nat. Dei,” § 49).

. The term essence, like person, has singular meaning when used in the doctrine of the Trinity. It denotes the one divine essence which in its totality and without any division is the property of each of the three Persons. We sometimes say that three persons have the same essence. This is correct if we use the term as a universal proposition, an intellectual abstraction, or a philosophical (nominalistic) concept, to denote a characteristic which is common to everyone in an entire class or genus. This definition, however, does not apply to the doctrine of the Trinity. The one divine essence of the three Persons is a true reality, because there is only one such essence which belongs to each person wholly and without division, in fine, is the true God. This is the doctrine of the teachers of our Church. Chemnitz, for example, points out that while the essence of man is said to be communicable, in reality it is only a universal concept, which does not actually exist per se, but is only inferred in the thought and conceived of by the intellect. The divine essence, however, is communicable, is not an abstract concept, a genus, or a species, but is a true reality. He refers to Augustine’s excellent statement: “Essence is ascribed to the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, but not in the common sense when various species are said to have a common genus, or a number of individuals are said to belong to the same species, or when that which is applied to the whole is applied also to its parts. Essence is ascribed to the three Persons in an ineffable and incomprehensible manner.” Chemnitz reminds us also of Augustine’s splendid rule: “If you cannot find out what God is, beware lest you make Him what He is not.” The Church therefore does not use the term essence in the philosophical meaning of a universal term, but as the truly existing divine nature, which is communicable and is therefore common to all three Persons and is totally and entirely in each Person. Chemnitz concludes: “I do not know what the essence of God is unless we say that the divine attributes are God’s essence itself.” (Loci, I, p. 38 sq.) Gerhard defines the term essence in almost the same words as Chemnitz: “The ‘essence of man’ is a universal term, which does not actually exist per se, but is only inferred in thought and conceived by the intellect. But as used of the Godhead, essence is not an imaginary something, as genus or species, but actually exists, though it is communicable” (Loci, locus “De Nat. Dei,” § 49).

Luther explains how we must view the numerical unity of the divine essence and the Trinity of Persons in the following words: “By his birth from another, man becomes not only an individual person, distinct from his father, but also an individual substance, being, or essence. There is no absolute identity between the being of the father and the son. But here [in the Divine Majesty] the Son is born as a Person distinct from the Father, and yet His being remains identical with the Father’s. As to persons they are distinct, but as to essence they retain absolute unity. When one man is sent on a mission by another, then the two are separate not only as to their person, but also as to their essence. In the Trinity, however, the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, even as He is sent by the Father and the Son and assumes a distinct personality, but in such a way that He remains in the Father’s and the Son’s essence, and that the Father and the Son remain in the Holy Ghost’s essence. In other words, all three Persons retain the absolute unity of one and the same Godhead. The theologians define the Son’s birth as an immanent generation, which in no way takes place outside the Divine Being, but originates in the Father alone and therefore remains in the deity. Likewise the procession of the Holy Spirit is known as an immanent procession, because it occurs alone within the Father and the Son and allows for no separation from the deity. The manner of this relation is a matter of faith. Even the angels, who constantly behold this majesty with joy, cannot fathom it. All who have tried to understand it have broken their necks.” (St. L. X:1008 f.)

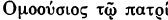

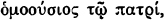

4. ‘ , consubstantial, or coessential, with the Father. The Nicene formula the Son is

, consubstantial, or coessential, with the Father. The Nicene formula the Son is  of the same essence with the Father, on the one hand condemns Arianism, which called Christ the first creature,

of the same essence with the Father, on the one hand condemns Arianism, which called Christ the first creature,  (“and made Him only a cosmic agent through whom God created the world”), and on the other hand expresses the Scriptural truth that the Son is of one essence, unius numero essentiae, with the Father. Luther declares emphatically and correctly that this term teaches no new doctrine, but expresses the doctrine of Scripture in opposition to the Arian heresy. Luther said: “The Council did not discover this article or set it up as something that was new and had not existed in the Church before, but only defended it against the heresy of Arius… . Otherwise what would have become of the Christians who, before the Council, for more than three hundred years, since the days of the Apostles, had believed and had prayed to the dear Lord Jesus and called upon Him as true God and had died for it and had been miserably persecuted?” (St. L. XVI:2188 f.) “Homoousios means ‘of one essense, or nature,’ not two, as the Church Fathers determined at Nicaea and as is sung in the Latin creed, consubstantialis; some coexistentialis; coessentialis” (St. L. XVI:2211). Athanasius understood the term homoousia to denote the numerical unity of the essence, because he rejected every division of the divine essence and maintained: “One They are, the Son and the Father, as to peculiarity and relation of the nature and as to the identity.” 48

(“and made Him only a cosmic agent through whom God created the world”), and on the other hand expresses the Scriptural truth that the Son is of one essence, unius numero essentiae, with the Father. Luther declares emphatically and correctly that this term teaches no new doctrine, but expresses the doctrine of Scripture in opposition to the Arian heresy. Luther said: “The Council did not discover this article or set it up as something that was new and had not existed in the Church before, but only defended it against the heresy of Arius… . Otherwise what would have become of the Christians who, before the Council, for more than three hundred years, since the days of the Apostles, had believed and had prayed to the dear Lord Jesus and called upon Him as true God and had died for it and had been miserably persecuted?” (St. L. XVI:2188 f.) “Homoousios means ‘of one essense, or nature,’ not two, as the Church Fathers determined at Nicaea and as is sung in the Latin creed, consubstantialis; some coexistentialis; coessentialis” (St. L. XVI:2211). Athanasius understood the term homoousia to denote the numerical unity of the essence, because he rejected every division of the divine essence and maintained: “One They are, the Son and the Father, as to peculiarity and relation of the nature and as to the identity.” 48

Gieseler finds a contributory cause of Arius’ heresy in the fact that he had been trained in the historico-exegetical school of Antioch under the Samosatanian Lucian (Kirchengesch. I, 369). The real cause of the Arian controversy, however, has been given by Luther: “Into this fair and peaceful paradise and peaceful time came the Old Serpent and raised up Arius, a priest of Alexandria, against his bishop. He wanted to bring up a new doctrine against the old faith and be a man of importance; he attacked his bishop’s doctrine, saying that Christ was not God; many priests and great, learned bishops followed him, and the trouble grew in many lands, until at last Arius ventured to declare that he was a martyr, saying that he was suffering for the truth’s sake at the hands of his bishop, Alexander, who did not countenance this teaching and wrote scandalous letters against him to all countries.” (St. L. XVI:2186.) Gieseler’s historical judgment as to the genesis of Arianism is strange, indeed, for it is impossible that a truly exegetical training will ever lead a person to the denial of the deity of Christ, the Trinity, the Vicarious Atonement, or the inspiration of Scripture. Liberal theology claims that deeper insights into the Scripture and a “recapture of the culture of the Bible” demand a re-interpretation and a re-definition of the Scriptural terms. This is only a subterfuge for the denial of the fundamentals of our Christian faith. The true exegetical training consists in this, that, as Luther says, we deal with Scripture in such a way as to remember at all times that God speaks to us, and that we continue in Christ’s Word in spite of our human opinions (John 8:31-32). The genesis of Arianism and of every form of heterodox teaching — including the heterodoxy of our day — has been exposed in 1 Tim. 6:3 f.: the turning away from the wholesome words of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the resultant inflation, being bloated with one’s own wisdom. Expressed in modern terms, the origin of heresy is the formulation of doctrine on the basis of the religious self-consciousness of the theologizing subject. According to Horst Stephan, Luther and Melanchthon “were too accustomed to view the Bible as the only source of doctrine and the old Confessions as a summary of Bible teaching.”49 In support of the charge that Luther was tradition bound, Stephan quotes Luther: “This article (concerning the Trinity as taught by the Fathers according to Moses and the Apostles and defended against the heretics) has come to us as a precious heritage, and God has preserved it until this day against all heretics. Let us in due simplicity retain it and not become wise in our own conceit.” (St. L. XII:656.) There is no traditionalistic spirit in Luther’s theology. On the contrary, Luther’s theology is based on the principle that “our God will save those who do not profess to be wise, but simply believe the Word, while those who follow their reason and despise the Word shall go to their doom in their vaunted wisdom.” 5. The term Filioque expresses the truth that the Holy Spirit proceeds not only from the Father, but also from the Son. It is generally accepted that this term was added to the Niceno-Constan-tinopolitan Creed by the Synod of Toledo (589). But the term is later than the doctrine. Even though the Christians of the first centuries did not know the term, they believed the fact of the Filioque on the basis of Scripture, which called the Holy Spirit not only the Spirit of the Father (Matt. 10:20), but also the Spirit of the Son (Gal. 4:6). Scripture, furthermore, ascribes the sending of the Spirit to the Son (John 15:26; 16:7) as well as to the Father (John 14:16). In fact, it adds the significant expression that the Holy Spirit would not speak of Himself, but shall receive His message from the Son (John 16:13-14), and is therefore called the “breath of His [the Messiah’s] lips” (Is. 11:4), and the “Spirit of His mouth” [the Word] (2 Thess. 2:8). The procession of the Spirit from the Son is also clearly indicated in John 20:22, when Christ breathed on His disciples and said, “Receive ye the Holy Ghost.”50

6.  , circumincessio, interpenetration, immanence. These terms express the fact that each Person has the one divine essence and that therefore the three Persons are in one another and reciprocally interpenetrate, interpermeate, each other.51

, circumincessio, interpenetration, immanence. These terms express the fact that each Person has the one divine essence and that therefore the three Persons are in one another and reciprocally interpenetrate, interpermeate, each other.51

This is clearly taught in John 14:11 (“I am in the Father and the Father in Me”); John 17:21. Nevertheless, according to Scripture, it does not follow from this mutual immanence that the Father and the Holy Spirit became man when the Son was made flesh. Only the “would-be-wise heretic,” as Luther said, pretends to penetrate this mystery.

7. Opera divina ad intra and opera divina ad extra. It has been said, especially in our day, that in these technical terms the entire apparatus of the ecclesiastical terminology in the doctrine of the Trinity has reached the climax of sophistry and is the apex of unintelligible and meaningless jargon.52 But these terms are not based on sophistry, but rest on Scripture. Neither are they unintelligible and meaningless. As was pointed out previously, Luther did not hesitate to use these terms in sermons preached to the common man. The term opera ad extra denotes the divine works which relate to the world, which have the universe as their object, such as creation, preservation, building of the Church. These works, as was shown above, are common to all three persons, because there is only one divine essence, not three; only one set of divine attributes and works, not three. Opera divina ad extra sunt indivisa. Opera divina ad intra are those divine works which have no bearing upon the world, but take place within the Deity. Luther calls the opera ad intra works which “remain in the Deity,” which do “not extend beyond the Deity.” Such works are the eternal generation of the Son and the eternal spiration of the Holy Ghost. In designating the Son as the Only-Begotten of the Father (John 1:14), the Scriptures reveal an intertrinitarian act which emanates from the Father and affects the Son. Likewise the fact that the Holy Spirit is called the Spirit of the Father (John 15:26; Matt. 10:20) and the Spirit of the Son (Gal. 4:6; Rom. 8:9) is the revelation of an act within the Divine Majesty of which the Father and the Son are the subject and the Holy Spirit the object. By revealing these “intertrinitarian” divine works, Scripture reveals in unmistakable terms that there are three distinct Persons in the one divine essence. The names Father, Son, and Holy Ghost are personal propositions.

The opera ad intra are not common to all three Persons, as are the opera ad extra, but are ascribed only to one or two Persons. The generation of the Son is ascribed only to the Father, the spiration of the Holy Ghost only to the Father and the Son, and thereby the Father is revealed as a Person distinct from the Son, and the Holy Spirit as distinct from the Father and the Son. Each of these intertrinitarian acts belongs only to one Person (opera ad intra divisa sunt), and these acts are, therefore, very properly designated as personal acts within the Divine Majesty (actus personales). This additional terminology became necessary to defend and uphold the distinction of the three Persons against Unitarianism and to condemn any and every confusion of the three Persons. Because personal acts are predicated of each of the three Persons, we must also ascribe to each a specific personal attribute: to the Father, paternity; to the Son, filiation; and to the Holy Spirit, passive spiration, or procession. The term “personal properties” serves the purpose of maintaining the distinction of the Persons and prevents the confusion of them. From the personal properties flow the “personal notations,” which amount to negative or passive attributes and are, in the case of the Father, the incapability of being born or proceeding, innascibilitas et improcessibilitas; in the case of the Son, nascibilitas, sive generatio passive talis, and in the case of the Holy Spirit, processio sive spiratio passiva. These terms express the same truth which is confessed in the Athanasian Creed, “The Father is made of none; neither created nor begotten. The Son is of the Father alone; not made, nor created, but begotten. The Holy Ghost is of the Father and of the Son; neither made, nor created, nor begotten, but proceeding.” 53

This terminology is not meaningless jargon, but necessary theological apparatus. Of course, Christians might wish that the Church would never have been troubled by Unitarians and therefore would have had no occasion to formulate this terminology. Christians say with St. Paul: “I would they were even cut off which trouble you” (Gal. 5:12). But, as Chemnitz points out (Loci I, 36 sqq.), this terminology became necessary on account of the errors and the treachery of the heretics. What effrontery when Stephan claims that this terminology is nothing but “human speculation,” “artificial theory,” and “meaningless”! This reckless statement finds its counterpart in the Modernist claim that Scripture does not claim inspiration and inviolability for itself. The fact is that the terminology used in connection with the opera ad intra is in full accord with the teaching of Scripture. Modern theologians are, of course, at liberty to refuse to believe the Bible. They may also charge Luther with being “Scripture bound” and traditionalistic and therefore unable to break with the ecclesiastical terminology which summarizes the Biblical doctrines. But honest scholarship should have kept them from making the assertion that this terminology is not in accord with the content of Scripture and is nothing more than human speculation. In reality this terminology expresses the simple faith which every Christian believes on the basis of clear Scripture passages even though he has never heard of these terms. Every Christian believes that the Son is the Only-Begotten of the Father and that the Holy Ghost is the Spirit of the Father and of the Son. Therefore he believes implicitly the actus personales (generation and spiration), the proprietates personales (paternity, etc.), and the allegedly meaningless notiones personates (innascibility, etc.).

But why — ask the less outspoken anti-Trinitarians — why encumber these self-evident truths with a whole battery of ecclesiastical terms? We have the heretics to thank for this situation. The Church did not invent these terms from an itch for novelty (Chemnitz says: “Not from any mischievous desire for innovation”), much less from a sort of malice to worry future generations. But the terminology has become necessary because the enemies of the Church have constantly devised new perversions of God’s Word and devious subterfuges to attack God’s self-revelation. In one way or another they have consistently endeavored to change the concept divine persons into operations or wills or powers. Even the so-called conservative wing of Modernist theology travels this evil road. An examination of the modern theologian’s alleged “deeper insight into the concept person” shows that he also believes that the concept person is nothing more than divine power, will, or operation. The ecclesiastical terminology opera ad intra and ad extra is therefore far from “meaningless,” and even today it is very much in order. The Church has always been compelled to fight Unitarianism. At Luther’s time some labored under the delusion that in spite of their denial of the Trinity they could be members of the Christian Church. Luther was constrained, therefore, to emphasize the doctrine of the Trinity not only in his writings, but also in his sermons, and in his polemics against Unitarians he did not hesitate to employ the ancient ecclesiastical terminology, even the terms opera ad intra and opera ad extra, setting forth that these terms are in full accord with Scripture.

The question has been raised: Can we expect our people to understand the nature and manner of the Son’s eternal generation from the Father and the Holy Spirit’s eternal procession from the Father and the Son? Obviously the answer must be in the negative. But neither can the trained theologian understand the mystery of the Trinity. Every wise theologian will confess: Quid sit nasci, quid processus, me nescire sum professas. Baier says very correctly: “It is certain that there is a distinction between the Son’s generation and the Spirit’s procession, but it is impossible to define more fully the manner in which they differ” (Compend. II, p. 69). In other words, the difference between the Son’s generation and the Spirit’s procession is not abstract, transcendent, notional, but is real, because the terms employed by Scripture establish a real difference. The attempt to go beyond the fact of the distinction and to explain its nature is contemptible presumption. And whoever endeavors independently of God’s self-revelation to penetrate the Divine Majesty, which dwells in a light to which no man can approach (1 Tim. 6:16), attempts the impossible. Luther reminds us that not even the angels can fathom this mystery, and all who have tried it have broken their necks. (St. L. X:1008 f.)

The destructive criticism and the deep-seated hatred with which modern theology approaches the term opera ad intra need not surprise us. Because there are eternal opera ad intra, that is, eternal personal acts, in the divine Majesty (the eternal generation of the Son and the eternal spiration of the Holy Ghost); and because there are also proprietates and notiones personales (there never was a time when the Father was not the Father, when the Son was not born of the Father, etc.), Unitarians, including the Subordinationists and the advocates of the so-called economic, or temporal, trinity, do not have a leg to stand on; on the contrary, the truth as expressed in Aug. Conf., Art. I, stands irrevocable: “There is one divine essence, and there are three Persons of the same essence and power, who also are co-eternal.” No wonder that in this point — just as in the doctrine of inspiration — a theology which has turned its back on Scripture haughtily renders the verdict: “Artificial theories, human speculations, meaningless, noxious terms.”

We believe it proper and beneficial to give the floor once more to Luther and Chemnitz on the terms opera ad intra and opera ad extra. In his commentary on The Last Words of David Luther offers a very detailed presentation of the doctrine of the Trinity, based on both the Old and the New Testament. (St. L. III:1884 ff.) Throughout this treatise Luther directs his warning against those who rely on their vaunted wisdom and attempt to judge this doctrine according to reason. He says: “Here Madam Wiseacre, our reason, which is ten times wiser than God Himself, takes offense.” “Such highly intelligent people are the Jews, Mahomet, the Turks, and the Tartars; they claim to comprehend the incomprehensible essence of God in the spoon or nutshell of their reason and say: God has no wife; therefore He can have no Son. Shame, shame, shame upon you, the devil, with the Jews and Mahomet and all those who are the pupils of blind, foolish, miserable reason in these high matters which no one understands but God Himself and which we can understand only to the extent in which the Holy Ghost has revealed them to us through the Prophets.” It is noteworthy that Luther, throughout this treatise, employed ecclesiastical terminology, opera ad intra, etc. “Here every Christian must follow the Athanasian Creed and be very careful lest he confound the Persons into one Person or divide the one divine essence into three Persons. If in the realm of creation, that is, outside the Trinity [ad extra] I were to ascribe to each Person a specific work in which the other two would not share, then I would divide the one Godhead and posit three gods or creators. That is wrong. And again, if within the Deity, or outside and beyond creation [ad intra] I do not ascribe to each Person a distinct characteristic which cannot be said of the other two, then I have confounded the three Persons into one Person, and that, too, is wrong. St. Augustine’s rule, therefore, applies: Opera trinitatis ad extra sunt indivisa. The divine works performed by God outside the Deity cannot be divided. In other words, the Persons dare not be divided according to their works, nor dare their specific work from without [ad extra] be ascribed to each Person. Within the Godhead [ad intra] the Person must be distinguished. But every work outside the Godhead must be assigned to all three Persons without distinction. For example: The Father is your and my God and Creator. But the Son has done the same work, and He also is your and my God and Creator as well as the Father. The Holy Spirit has also performed the same work which has brought you and me into existence and is therefore your and my God and Creator just as well as the Father and the Son. And yet there are not three gods, three creators, but only one God and Creator, who has made both you and me. This my confession is my bulwark against the Arian heresy which divides the divine essence into three gods and creators, whereas I confess that there is no more than one God and Creator. — On the other hand, when I step outside creation and into the inner, infinite being of the divine God, then — following Scripture and not reason — I find that in this one indivisible eternal Deity the Father is an entirely different Person from the Son. His distinctive property is that He is Father and therefore does not receive the deity from the Son nor from another. The Son is a Person distinct from the Father in the one divine Godhead of the Father. His distinctive personal attribute is that He is a Son, that He possesses the deity not from Himself, but only from the Father through the eternal generation. The Holy Spirit is a Person distinct from the Father and the Son in the same one Godhead. His personal attribute is that He proceeds from the Father and the Son and has the deity from no one but the Father and the Son. This relation is unchangeable from eternity to eternity.54 And with this my confession (of my faith in the three distinct Persons) I take my stand against the Sabellian heresy, against Jews and Mohammedans, and all who would be wiser than God. I do not confound the Persons into one Person, but in the true Christian faith I retain three distinct Persons in the one, divine, eternal essence, even though these three Persons in their relation to us and to the entire creation [ad extra] are one God and Creator. This distinction may be too subtle and academic for us Germans and should be confined to the schools. Nevertheless, it is necessary to discuss this doctrine in theological terminology. We see that in these last times the devil switches his tail,55 as though he would incite to all manner of new heresies. We hear how the world in its folly itches to hear something new, loathes sound doctrines (2 Tim. 4:3), and thus opens wide the door to the devil to introduce whatever he wills. It is therefore beneficial, yes, necessary, that there are more, both among the laity and especially among the clergy, who can present these articles of our faith in clear and precise terminology. Let him who finds this too difficult stay with the children’s catechism and pray against Satan and his heretics, against the Jews and Mohammedans, that they may not lead him into temptation.” Chemnitz presents the same views (Loci I, 40sq.): As to the rule Opera Trinitatis ad extra sunt indivisa, he shows that Scripture teaches it. “Because Scripture says: ‘Let us make’ (Gen. 1:26) and John 5:19: ‘What things soever He [the Father] doeth, these also doeth the Son likewise’; John 14:10: ‘the Father that dwelleth in Me, He doeth the works’; and again, John 5:17: ‘My Father worketh hitherto, and I work’; John 16:15: ‘All things that the Father hath are Mine… . He [the Spirit] shall take of Mine and shall show it unto you.’ These passages show in a fine way how the opera ad extra are common to all three Persons.” As to the value of the Augustinian rule Opera Trinitatis ad intra sunt divisa, etc., Chemnitz points out that the formulations are not merely academic niceties and erudite distinctions. Since God wants to be known, invoked, and proclaimed only as He has revealed Himself, we must make every effort that our thoughts concerning these mysteries are pious and our words reverent. We should therefore studiously emulate the care of the ancient Fathers in their controversy with the anti-Trinitarians and take to heart Jerome’s words: “From inexact speech springs heresy.”

But has the Church consistently observed the Augustinian rule: Opera ad extra indivisa sunt? Does not the Apostles’ Creed ascribe to each Person a special opus divinum ad extra: to the Father, creation; to the Son, redemption; to the Holy Spirit, sanctification? Does not the second part of Luther’s Small Catechism actually mislead Christian people to a “naive tritheism” by dividing the divine works among the three Persons? 56 This objection to the Church’s terminology does not rest on fact. In the first place, no orthodox teacher speaks of a division and distribution of the opera ad extra unless the tongue or the pen has slipped. Furthermore, while the Church uses the terms attribution and appropriation, it does not use the term distribution. The former terms have Scriptural basis because Scripture attributes the work of creation especially to the Father. This is clearly taught in those passages which state that the Father created the world through the Son (Col. 1:15-16; Heb. 1:2); and through the Holy Ghost (Ps. 33:6). This is evident from all those passages which tell us that the Son became man, gave Himself for us, redeemed us from the curse of the Law (John 1:14; 1 Tim. 2:6; Gal. 3:13). Scripture attributes the work of redemption especially to the Son. And whenever the Scriptures say that the Holy Spirit convicts the world (John 16:8-11), that He glorifies Christ (v. 14), that He guides into all truth (v. 13), that He is the Spirit of adoption (Rom. 8:15-16), Scripture ascribes the work of sanctification especially to the Holy Ghost.

In other passages, however, Scripture teaches just as clearly that the three works are common to all three Persons. The work of creation is also the work of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. This becomes evident from such passages as speak of the world being created by the Son and by the Spirit (Ps.33:6; Col. 1:16; John 1:3), and especially from those references where the work of creation is attributed to the Son and the Holy Ghost directly (Heb. 1:10; Job 33:4). Likewise the work of redemption is attributed also to the Father, because He gave His only-begotten Son and reconciled the world (John 3:16; 2 Cor. 5: 18-19); and also to the Holy Ghost, because Christ, according to His human nature, was conceived of the Holy Ghost (Matt. 1:20) and because the Holy Spirit rested upon Christ (Is. 61:1; Luke 4:18). Finally, the work of sanctification is also the work of the Father, and of the Son, for both sent the Spirit (John 14:16, 26; 16:7; 15:26; Acts 2:33); the Father has elected us unto sanctification (2 Thess. 2:13), and the Son sanctifies us through His Word (John 17:19), and He is made unto us sanctification (1 Cor. 1:2, 30). Scripture therefore teaches the twofold truth: 1) That each of the opera ad extra (creation, redemption, sanctification) must be attributed to one Person in particular; 2) that the same works must be ascribed to all Persons (opera tribus personis communi ).

).

The opera ad extra are common to all three Persons because each of the Persons has the divine essence entirely and indivisibly. In relation to the creatures (ad extra) each Person has the same attributes and the selfsame works. The fact that Scripture, on the one hand, attributes the opera ad extra to each of the Persons, and, on the other hand, makes them common to the three Persons, is another proof (Luther would say “revelation”) of the ontological, or essential Trinity. Luther treats this point at great length, though he realizes that this matter is profound and difficult. He raises the question: “Why does Scripture teach us to say, ‘I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker,’ etc., and does not teach us to call the Son the Maker? Why, ‘And in Jesus Christ, conceived by the Holy Ghost’? Why, ‘I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Giver of Life, who spake by the Prophets’? In these words of the Creeds we ascribe to each Person externally [ad extra] a special and distinct work, even as the Persons are distinct, internally [ad intra].” (St. L. III:1923.) To make his point clear, Luther distinguishes between an “absolute” and a “relative” study of creation. Viewed absolutely, the works of creation tell us nothing of a Triune God because every work is the work of the one God. But we must study God’s works also relatively, that is, in their relation to us, for in such study of His creatures God intends to illustrate the Trinity to us. God employs the dove to picture and reveal the Holy Spirit as an externally distinct Person. The dove may never be used as a picture of the Father or of the Son, but only of the Holy Spirit, in order to assure us that the eternal essence exists in three distinct Persons from all eternity (Luke 3:22). The Son is revealed to us in the form of man, a humble and obedient man (Phil. 2:7). Though the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit have created this humanity, this specific creation, according to God’s good pleasure, is the means to reveal in a specific way the Son. By coming in the fashion of man, the Son made Himself known as a distinct Person. Again, the Father has revealed Himself as a distinct Person in the voice, a revelation restricted to the Father. To illustrate his point, Luther refers to the analogy employed by such men as Bonaventura: If three girls put a dress on one of the three, each one would have a part in putting on the dress, and yet only the third one is actually being clothed. In like manner we must understand that all Persons in God, one in essential unity, have created a unique human nature and united it with the Son in His Person, but in such a manner that only the Son actually assumed the human nature. Likewise the dove and the voice are adopted by the Holy Spirit and the Father respectively as the means of the revelation. When we confess in the Creed, “I believe in God the Father,” etc., we do not mean to say that only the Father is almighty, the Creator, because we believe that also the Son and the Holy Spirit are the Creator. Yet there are not three Almighties, as little as there are three Saviors, or three Sanctifiers, though the Father and the Holy Spirit are also our Redeemer, and the Father and the Son are also our Sanctifier. Opera ad extra indivisa sunt, sic cultus Trinitatis indivisa est. We must, therefore, accept and believe the three Persons in the one divine essence, neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the essence. (St. L. III: 1923–1929.)57

In this connection two specific questions must be answered:

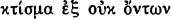

1. Is the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father (John 15:26),  , temporal or eternal, or both? — Luther and the Lutheran dogmaticians consider it practically self-evident that John 15:26 teaches not the temporal, economic, but the eternal (ontological, Trinitarian) procession from the Father. The Athanasian Creed defines the

, temporal or eternal, or both? — Luther and the Lutheran dogmaticians consider it practically self-evident that John 15:26 teaches not the temporal, economic, but the eternal (ontological, Trinitarian) procession from the Father. The Athanasian Creed defines the  as the eternal procession. Hofmann, Meyer, Luthardt, Klostermann, say that the procession in John 15:26 refers only to temporal procession, while Olshausen, Stier, Lange, and Godet restrict it to eternal or inter-Trinitarian. De Wette’s comments on this passage are entirely misleading and emanate from his false view of the Trinity. He says that the words “proceeded from the Father” do not pertain to the Spirit’s essence, but only to His appearance in His activity within the Christian Church. De Wette’s view, however, is false, for the words “whom I will send” speak of the temporal appearance, while the subordinate clause “which proceedeth,” etc., clearly and definitely speaks of the eternal and essential relation of the Holy Spirit to the Father. Luthardt contradicts himself in his attempt to restrict the words “who proceedeth,” etc., to the economic and temporal procession. He says that the statement “who proceedeth,” etc., and “whom I will send” are parallel because in both instances the words “from the Father” are added. True, but we note that the tense changes:

as the eternal procession. Hofmann, Meyer, Luthardt, Klostermann, say that the procession in John 15:26 refers only to temporal procession, while Olshausen, Stier, Lange, and Godet restrict it to eternal or inter-Trinitarian. De Wette’s comments on this passage are entirely misleading and emanate from his false view of the Trinity. He says that the words “proceeded from the Father” do not pertain to the Spirit’s essence, but only to His appearance in His activity within the Christian Church. De Wette’s view, however, is false, for the words “whom I will send” speak of the temporal appearance, while the subordinate clause “which proceedeth,” etc., clearly and definitely speaks of the eternal and essential relation of the Holy Spirit to the Father. Luthardt contradicts himself in his attempt to restrict the words “who proceedeth,” etc., to the economic and temporal procession. He says that the statement “who proceedeth,” etc., and “whom I will send” are parallel because in both instances the words “from the Father” are added. True, but we note that the tense changes:  , future;

, future;  , present tense. When the Savior uses the future tense, He clearly and unmistakably is speaking of the economic and temporal activity, which the Holy Spirit would initiate after Christ’s ascension. The same is true of

, present tense. When the Savior uses the future tense, He clearly and unmistakably is speaking of the economic and temporal activity, which the Holy Spirit would initiate after Christ’s ascension. The same is true of  , “He will testify of Me.” It is significant that the phrase in the present tense, “who proceedeth,” is placed between the two phrases with the future tense. This change of tense prevents us from co-ordinating temporally the procession with the sending and testifying. On the contrary, we are compelled to accept the procession as an eternal and timeless act. If the procession referred only to the Spirit’s activity, then the Savior would have used the future:

, “He will testify of Me.” It is significant that the phrase in the present tense, “who proceedeth,” is placed between the two phrases with the future tense. This change of tense prevents us from co-ordinating temporally the procession with the sending and testifying. On the contrary, we are compelled to accept the procession as an eternal and timeless act. If the procession referred only to the Spirit’s activity, then the Savior would have used the future:  .58

.58

2. As modern theologians appeal to Luther in defense of their denial of Inspiration, they also appeal to Luther with regard to their rejection of the terminology of the ancient Church. Did Luther subscribe ex animo to the ancient terminology, especially the terms trinitas and  ? — This question is in order because Luther appears to speak quite disparagingly of these terms. We have already discussed Luther’s attitude toward the term Trinity (Dreifaltigkeit). In his treatise against Latomus (1521) Luther says that “his soul loathed the word

? — This question is in order because Luther appears to speak quite disparagingly of these terms. We have already discussed Luther’s attitude toward the term Trinity (Dreifaltigkeit). In his treatise against Latomus (1521) Luther says that “his soul loathed the word  ” (St. L. XVIII:1182). The reference reads: “Assuming the case (quod si) that my soul loathes the word

” (St. L. XVIII:1182). The reference reads: “Assuming the case (quod si) that my soul loathes the word  and that I would not want to employ it, I would not thereby become a heretic, for who can compel me to use this term as long as I accept the doctrine which the Council [at Nicaea] formulated on the basis of God’s Word?” Luther speaks conditionally, and his statement is no more than a protest against the substitution of human terminology for the clear Word of God. Under the same or similar conditions, we, too, would use similar language. As Philippi points out (Glaubenslehre, 2d ed., II, 156 f.), ecclesiastical terminology has only a hypothetical and relative, not an absolute, necessity. This was Luther’s position to the end of his life. As late as 1543 he advised those who find the ecclesiastical terminology too difficult simply to retain the simple Catechism truths. (St. L. III:1920 f.) But in his condemnation of Arianism, Luther unequivocally accepted the term homoousios, as is evident from his treatise Of Councils and Churches. Luther says: “When they [the Church Fathers in their opposition to Arius] came to the heart of the matter, namely, that Christ is homoousios with the Father, the Arians could no longer find any trick or loophole or ruse or wile, for the plain fact is that the term homoousios adopted by the Fathers at Nicaea means, ‘of one and the same essence, or nature,’ and not, ‘of two natures.’ Christ is consubstantialis (so the Latin Creed), or coexisientialis and coessentialis (thus some of the Fathers). At Nicaea the Arians had accepted the term homoousios and employed it when they discussed the doctrine of the Trinity in the presence of the emperor and the Church Fathers. But in their own schools they attacked the word vehemently, their argument being that the word is not found in the Scriptures. They convened many councils, even as late as in the reign of Constantine, with the one design to weaken and undermine the Nicene Council. Their maneuvers caused untold confusion and so alarmed the men of our party that even Jerome in his perplexity petitioned Damason, bishop of Rome, to delete the word homoousios. ‘I have no idea,’ says Jerome, ‘what kind of poison is in this word which makes it so objectionable to the Arians.’ A dialog has come down to us in which Athanasius and Arius disputed about the word homoousios before an official named Probus. When Arius insisted that the word is not in Scripture, Athanasius turned the tables on him and caught him in his own trap. ‘Neither does Scripture contain the words innascibilis, ingenitus Deus.’ And yet the Arians use these words to prove that Christ cannot be God because He was born, while God cannot be born. Probus decided against Arius. It is true, indeed, that in divine things we dare not teach anything outside the Scripture. This, however, does not mean that one dare not use more or other words than Scripture uses, especially in controversies when heretics employ subterfuges to distort the doctrine and to pervert Scripture. The Arians played a double game: In their own schools they perverted Scriptures by adding false comments, but before the emperor and the Council they would quote these passages without any comment. Therefore it became necessary to summarize the teaching of Scripture in one watchword and to ask the Arians whether they accepted Christ homoousios as the Scriptures so plainly teach in many instances. It is the same as when the Pelagians wanted to drive us into a corner because we employed the term ‘original sin’ or ‘Adam’s malady,’ since these terms do not occur in Scripture. But Scripture mightily teaches what these terms designate when it says that we were conceived in sin (Ps. 51:5), are by nature the children of wrath (Eph. 2:3), and are all sinners by one man’s transgression (Rom. 5:12).” (St. L. XVI:2211 f.)

and that I would not want to employ it, I would not thereby become a heretic, for who can compel me to use this term as long as I accept the doctrine which the Council [at Nicaea] formulated on the basis of God’s Word?” Luther speaks conditionally, and his statement is no more than a protest against the substitution of human terminology for the clear Word of God. Under the same or similar conditions, we, too, would use similar language. As Philippi points out (Glaubenslehre, 2d ed., II, 156 f.), ecclesiastical terminology has only a hypothetical and relative, not an absolute, necessity. This was Luther’s position to the end of his life. As late as 1543 he advised those who find the ecclesiastical terminology too difficult simply to retain the simple Catechism truths. (St. L. III:1920 f.) But in his condemnation of Arianism, Luther unequivocally accepted the term homoousios, as is evident from his treatise Of Councils and Churches. Luther says: “When they [the Church Fathers in their opposition to Arius] came to the heart of the matter, namely, that Christ is homoousios with the Father, the Arians could no longer find any trick or loophole or ruse or wile, for the plain fact is that the term homoousios adopted by the Fathers at Nicaea means, ‘of one and the same essence, or nature,’ and not, ‘of two natures.’ Christ is consubstantialis (so the Latin Creed), or coexisientialis and coessentialis (thus some of the Fathers). At Nicaea the Arians had accepted the term homoousios and employed it when they discussed the doctrine of the Trinity in the presence of the emperor and the Church Fathers. But in their own schools they attacked the word vehemently, their argument being that the word is not found in the Scriptures. They convened many councils, even as late as in the reign of Constantine, with the one design to weaken and undermine the Nicene Council. Their maneuvers caused untold confusion and so alarmed the men of our party that even Jerome in his perplexity petitioned Damason, bishop of Rome, to delete the word homoousios. ‘I have no idea,’ says Jerome, ‘what kind of poison is in this word which makes it so objectionable to the Arians.’ A dialog has come down to us in which Athanasius and Arius disputed about the word homoousios before an official named Probus. When Arius insisted that the word is not in Scripture, Athanasius turned the tables on him and caught him in his own trap. ‘Neither does Scripture contain the words innascibilis, ingenitus Deus.’ And yet the Arians use these words to prove that Christ cannot be God because He was born, while God cannot be born. Probus decided against Arius. It is true, indeed, that in divine things we dare not teach anything outside the Scripture. This, however, does not mean that one dare not use more or other words than Scripture uses, especially in controversies when heretics employ subterfuges to distort the doctrine and to pervert Scripture. The Arians played a double game: In their own schools they perverted Scriptures by adding false comments, but before the emperor and the Council they would quote these passages without any comment. Therefore it became necessary to summarize the teaching of Scripture in one watchword and to ask the Arians whether they accepted Christ homoousios as the Scriptures so plainly teach in many instances. It is the same as when the Pelagians wanted to drive us into a corner because we employed the term ‘original sin’ or ‘Adam’s malady,’ since these terms do not occur in Scripture. But Scripture mightily teaches what these terms designate when it says that we were conceived in sin (Ps. 51:5), are by nature the children of wrath (Eph. 2:3), and are all sinners by one man’s transgression (Rom. 5:12).” (St. L. XVI:2211 f.)