_3_The Verbal Inspiration of Holy Scripture

The Scriptures not only tell us that they are the Word of God, but they also teach very clearly why they are the Word of God, namely, because they were inspired, or breathed into the writers, by God. 2 Tim. 3:16: “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God.” 2 Pet. 1:21: “Holy men of God spake as they were moved by the Holy Ghost.” This divine act of inspiration establishes the fact that the Holy Scriptures, though written by men, are the Word of God. The Scripture passages speaking of inspiration contain the following truths:

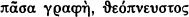

1. Inspiration does not consist in the so-called subject inspiration (Realinspiration), inspiration of the matter merely, nor in the so-called inspiration of persons (Personalinspiration), but it is verbal inspiration, suggestio verborum, since the Scriptures, which are said to be inspired, do not consist of things or persons, but of written words. As surely as 2 Tim. 3:16 predicates the  of the

of the  as subject, so certainly Verbal Inspiration is not a “subtle theory” of the old dogmaticians, but the plain teaching of Scripture itself. 2 Pet. 1:21 teaches the same thing. According to this passage, the holy men of God, being moved by the Holy Ghost, did not merely think or meditate, but they “spake,” that is, uttered words. And the preceding verse (v. 20) expressly states that the reference is to the written words of Holy Scripture; the words uttered by the holy men are defined as the “prophecy of the Scripture.” And, according to 1 Cor. 14:37, the Apostle Paul did not merely think or meditate in his heart on the commandments of the Lord, but wrote them to the Corinthians: “The things that I write unto you are the commandments of the Lord.” When Hastings says: 25 “Inspiration applies to men, not to written words,” he is asserting the very opposite of what Scripture teaches concerning inspiration. Hiley, as quoted by Gaussen,26 has the correct view: “The miraculous operation of the Holy Ghost [namely, the divine act of inspiration] had not the writers themselves for its object — these were only His instruments, and were soon to pass away — its objects were the holy books themselves.” Whoever rejects Verbal Inspiration and will accept only an inspiration of general ideas or of persons, thereby denies — from dogmatic bias — the Scripture doctrine of inspiration. To repeat, Scripture affirms of Scripture, which admittedly consists of words (verba), that it is inspired. Quenstedt (I, 107): “The Apostle does not say: ‘Everything in Scripture,

as subject, so certainly Verbal Inspiration is not a “subtle theory” of the old dogmaticians, but the plain teaching of Scripture itself. 2 Pet. 1:21 teaches the same thing. According to this passage, the holy men of God, being moved by the Holy Ghost, did not merely think or meditate, but they “spake,” that is, uttered words. And the preceding verse (v. 20) expressly states that the reference is to the written words of Holy Scripture; the words uttered by the holy men are defined as the “prophecy of the Scripture.” And, according to 1 Cor. 14:37, the Apostle Paul did not merely think or meditate in his heart on the commandments of the Lord, but wrote them to the Corinthians: “The things that I write unto you are the commandments of the Lord.” When Hastings says: 25 “Inspiration applies to men, not to written words,” he is asserting the very opposite of what Scripture teaches concerning inspiration. Hiley, as quoted by Gaussen,26 has the correct view: “The miraculous operation of the Holy Ghost [namely, the divine act of inspiration] had not the writers themselves for its object — these were only His instruments, and were soon to pass away — its objects were the holy books themselves.” Whoever rejects Verbal Inspiration and will accept only an inspiration of general ideas or of persons, thereby denies — from dogmatic bias — the Scripture doctrine of inspiration. To repeat, Scripture affirms of Scripture, which admittedly consists of words (verba), that it is inspired. Quenstedt (I, 107): “The Apostle does not say: ‘Everything in Scripture,  ).

).  ,’ but ‘All Scripture,

,’ but ‘All Scripture,  ,’ in order to show that not only the things written about, but also the writing itself is

,’ in order to show that not only the things written about, but also the writing itself is  . And whatever is said of the whole Scripture must of necessity be understood also of the words, not the most insignificant part of Scripture. For if one little word occurred in Scripture that is not suggested or divinely inspired, it could not be said that ‘All Scripture is given by inspiration of God.’ ” 27

. And whatever is said of the whole Scripture must of necessity be understood also of the words, not the most insignificant part of Scripture. For if one little word occurred in Scripture that is not suggested or divinely inspired, it could not be said that ‘All Scripture is given by inspiration of God.’ ” 27

We are unable to see that the rejection of Verbal Inspiration, while the inspiration of the subjects or of the thoughts is assumed, is based on sound thinking. We can get at the thoughts contained in a book only by means of the words it contains. The situation is the same in a book as in the case of a speech. We get at the thoughts of the speaker only by means of the words he uses, so far as the speaker is able and willing to clothe his thoughts in words. In the same manner we discover the thoughts of the author of a book only by means of the words he uses in that book, so far as the author is able and willing to express his thoughts in the written words. The same thing applies to God’s speech and God’s Scripture. Presupposing that God wants to deal with men by word of mouth, men have to take note of God’s words. Presupposing that God wants to deal with men by the written Word, men must take note of the written words. And since God is the Author of Scripture, we have the great advantage that He is perfectly capable and willing to clothe His thoughts in fully adequate words. Therefore Luther so consistently urges upon every Christian and every theologian to adhere to the exact wording of Scripture. He felt as if every passage of Scripture made the world too narrow for him (St. L. XX:788). He therefore gives the advice, as we have already heard, to cling to the words of Scripture as we cling with our hand to a wall or a tree. But why talk of Luther? Christ Himself has directed us to the words of Scripture. In His temptation He thrice opposes Satan with the words of Scripture and obtains the victory. Furthermore, referring to an individual word of Scripture (elohim,  , gods, John 10), He says that Scripture cannot be broken. And He binds us to His own words when He says (John 8): “If ye continue in My Word, then … ye shall know the truth.” But Christ’s words — we have to call attention to this truth again and again — we have in the words of His Apostles, as He expressly says in His high-priestly prayer (John 17) that all Christians to the end of time will believe on Him through their Word, through the Apostles’ Word. And the Apostle Paul says (1 Tim. 6:3) of all teachers who do not consent to the wholesome words of our Lord Jesus that they are proud and know nothing and only cause pernicious dispute and strife in the Church. The denial of Verbal Inspiration is unscriptural, foolish, and harmful.

, gods, John 10), He says that Scripture cannot be broken. And He binds us to His own words when He says (John 8): “If ye continue in My Word, then … ye shall know the truth.” But Christ’s words — we have to call attention to this truth again and again — we have in the words of His Apostles, as He expressly says in His high-priestly prayer (John 17) that all Christians to the end of time will believe on Him through their Word, through the Apostles’ Word. And the Apostle Paul says (1 Tim. 6:3) of all teachers who do not consent to the wholesome words of our Lord Jesus that they are proud and know nothing and only cause pernicious dispute and strife in the Church. The denial of Verbal Inspiration is unscriptural, foolish, and harmful.

2. Inspiration does not consist in mere divine guidance and protection against error (assistentia, directio, or gubernatio divina), but is a divine supplying or divine giving of the very words that constitute Scripture. The predicate  , applied to Scripture, teaches unmistakably that God not merely directed the writing of Scripture, but inspired the Scriptures. Within the Lutheran Church the Helmstedt theologian George Calixt (d. 1656) held that in regard to facts already familiar to the holy writers or to facts of less importance the Holy Ghost merely guided and protected the writers against error. Calixt’s doctrine was justly rejected by his Lutheran contemporaries as unscriptural, because “guided and directed by God” and “

, applied to Scripture, teaches unmistakably that God not merely directed the writing of Scripture, but inspired the Scriptures. Within the Lutheran Church the Helmstedt theologian George Calixt (d. 1656) held that in regard to facts already familiar to the holy writers or to facts of less importance the Holy Ghost merely guided and protected the writers against error. Calixt’s doctrine was justly rejected by his Lutheran contemporaries as unscriptural, because “guided and directed by God” and “ — given by inspiration of God” are two entirely different concepts. And it is of great practical importance that we permit no one to substitute a mere guidance and preservation from error for the

— given by inspiration of God” are two entirely different concepts. And it is of great practical importance that we permit no one to substitute a mere guidance and preservation from error for the  . This substitute would at best make Scripture an errorless human word, but never the living, majestic Word of God, throbbing with divine power. Scripture is God’s own Word only because of inspiration. Quenstedt (I, 98 sq.) writes against Calixt and some Romanists (Bellarmine): “One must distinguish between mere divine assistance and direction by which the holy writers in speaking and writing were only prevented from departing from the truth, and divine assistance and direction which included the inspiration and the dictation of the Holy Ghost. Not the former, but the latter makes the Bible

. This substitute would at best make Scripture an errorless human word, but never the living, majestic Word of God, throbbing with divine power. Scripture is God’s own Word only because of inspiration. Quenstedt (I, 98 sq.) writes against Calixt and some Romanists (Bellarmine): “One must distinguish between mere divine assistance and direction by which the holy writers in speaking and writing were only prevented from departing from the truth, and divine assistance and direction which included the inspiration and the dictation of the Holy Ghost. Not the former, but the latter makes the Bible  .”

.”

3. Inspiration covers not only a part of Scripture, e. g., the chief matters, the doctrines, and such things as were before unknown to the writers, etc., but the entire Scriptures. Every part of Scripture is inspired. That, and nothing less, is the meaning of “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God.” We would be doing violence to this statement of God if we excepted from inspiration those parts of Scripture that contain historical, geographical, scientific, etc., information or relate matters well known to the holy writers. It is by no means a clever objection to the inspiration of Holy Scripture when modern theologians remark that the Bible is no textbook of history or geography or natural science and that for that reason inspiration could not pertain to the historical, geographical, and scientific data.28 Of course, it is not the chief purpose of Scripture to give information on such points. The real purpose of Scripture is indicated in passages like John 5:39; 2 Tim. 3:15 ff.; 1 John 1:4. Scripture is to bring us human beings to the knowledge of Christ and thus to salvation. But also the historical data which are found in Scripture (for with His Word God has entered the history of mankind), though mentioned only incidentally, are inspired and infallible, because they are a part of Scripture. More about this later. Quenstedt (I, 98) does not go beyond 2 Tim. 3:16 when he says: “In the manner of inspiration we acknowledge no distinction (among the matters in Holy Scripture) and assert that the divinity inheres uniformly in the entire Scriptures… . The Scriptural matters differ in three ways: 1) Some were naturally utterly unknown to the sacred writers, either because of their sublimity, like the mysteries of faith, or because of non-existence, like contingent future events, or because of their being imperceptible to the senses, like the secrets of the heart. 2) Some were naturally indeed knowable, but actually unknown to the sacred writers, because of the antiquity and remoteness of the times and places, unless they accidentally became known to them in some other way, either by rumor, or by tradition, or by some human writing, like the history of the Deluge… . 3) Some were not only knowable, but were also naturally known to the public notaries of God through the proper search (historical research of Luke, ch. 1:1 ff.) and by their own observation, as the exodus of Israel from Egypt and the journey in the desert were known to Moses, the history of the Judges to Samuel, the life and deeds of Christ to the Evangelists and Apostles. Certainly not only first-class matters, but also second- and third-class matters were in the very act of writing immediately dictated and breathed into the holy amanuenses by the Holy Spirit, so that they would be attested by these and no other circumstances, in this and no other mode or order.”

4. The statement of Scripture that inspiration extends not merely to a part, but to the entire Scriptures, together with the fact that Scripture does not consist of persons or things, but of words, declares at the same time that Scripture is perfectly inerrant in all its words and in every one of its words. That is the meaning of Christ’s testimony to the Scriptures when He declares (John 10:35) concerning the use of a single word (Ps. 82:6;  ): “The Scripture cannot be broken.” Stoeckhardt is entirely right in saying: 29 “When Christ and the Apostles appeal to Scripture, they adduce not merely general Scripture thoughts, they are not even satisfied to quote single passages, but they often lay their finger on a single word of Scripture to prove their point. Paul writes Gal. 3:16: ‘Now to Abraham and his Seed were the promises made. He saith not, And to seeds, as of many, but as of one, And to thy Seed, which is Christ.’ To this single word: ‘And to thy Seed’ (Gen. 22:18), the singular of this noun, he attaches all weight and proves by it that Christ was already promised to Abraham, and he declares that God chose this term intentionally. In Matt. 22:43-44 Christ attests and proves to the Pharisees His deity from Ps. 110, and note that He proves it from the single word: ‘my Lord.’ In John 10:35 the entire emphasis lies on the term

): “The Scripture cannot be broken.” Stoeckhardt is entirely right in saying: 29 “When Christ and the Apostles appeal to Scripture, they adduce not merely general Scripture thoughts, they are not even satisfied to quote single passages, but they often lay their finger on a single word of Scripture to prove their point. Paul writes Gal. 3:16: ‘Now to Abraham and his Seed were the promises made. He saith not, And to seeds, as of many, but as of one, And to thy Seed, which is Christ.’ To this single word: ‘And to thy Seed’ (Gen. 22:18), the singular of this noun, he attaches all weight and proves by it that Christ was already promised to Abraham, and he declares that God chose this term intentionally. In Matt. 22:43-44 Christ attests and proves to the Pharisees His deity from Ps. 110, and note that He proves it from the single word: ‘my Lord.’ In John 10:35 the entire emphasis lies on the term  , elohim, ‘gods,’ that being the title given by Psalm 82 to the government… . If even the government officials are entitled to this name, how much more He whom the Father has sanctified and sent into the world! For Christ and the Apostles every sentence, every word they found and read in Scripture, was God’s Word in the strictest sense of the term. — Verbal Inspiration, which is so defamed in our day and is called ‘an invention’ of the dogmaticians,30 has a firm basis and support in Scripture. Every word of Scripture is an inviolable sanctuary, is the infallible, unchangeable Word of God. Scripture insists on that… . Scripture contains the earnest warning not to add to, nor to take away from, what God has commanded and spoken (Deut. 4:2; 12:32; Prov. 30:5-6; Rev. 22:18-19). Every addition is a sacrilege, since it dilutes God’s Word with the word of men. And the warning has the threat attached: ‘Add thou not unto His words, lest He reprove thee’ (Prov. 30:6)… . Christ raises His voice and declares: ‘I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill. For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the Law, till all be fulfilled. Whosoever therefore shall break one of these least commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven; but whosoever shall do and teach them, the same shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven.’ (Matt. 5:17-19.) Cp. Luke 16:17. We take Christ’s warning to heart and confess with Paul: ‘I believe all things which are written in the Law and in the Prophets’ (Acts 24:14).” Likewise Luther confesses: “The Scriptures have never erred” (St. L. XV:1481) and “One little point of doctrine is of more value than heaven and earth; and therefore we cannot abide to have the least jot thereof corrupted” (St. L. IX:650). The context shows that Luther has in mind every tittle of doctrine, inasmuch as the doctrine is expressed in the definite, inviolable words of Scripture. The point at issue over against the Sacramentarians was the words of the institution of the Lord’s Supper, and Luther adds: “If they believed that the Word is God’s, they would not play with it in such a manner, but would hold it in highest esteem and without any dispute or doubt regard it as credible, and would know that one word of God is all words of God and all words of God are one word of God.” Quenstedt has made statements with regard to the infallibility of the words of Scripture at which the camp of modern theologians throws up its hands in horror. And yet Quenstedt does not say one whit more than what the Scriptures say of themselves. He writes (Systema I, 112): “The canonical Holy Scriptures in the original text are the infallible truth and free from every error, or, in other words, in the canonical Holy Scriptures there is found no lie, no falsity, no error, whether in the things or in the words; but all things, and each single one, that are handed down in them are the most true, whether they pertain to doctrine or morals or history, chronology, topography, or nomenclature; no ignorance, no thoughtlessness or forgetfulness, no lapse of memory, can or dare be ascribed to the amanuenses of the Holy Ghost in their penning of the sacred writings.” Likewise Calov (Systema I, 551) says: “No error, even in unimportant matters, no lapse of memory, not to say untruth, can have place in the whole of Scripture.”

, elohim, ‘gods,’ that being the title given by Psalm 82 to the government… . If even the government officials are entitled to this name, how much more He whom the Father has sanctified and sent into the world! For Christ and the Apostles every sentence, every word they found and read in Scripture, was God’s Word in the strictest sense of the term. — Verbal Inspiration, which is so defamed in our day and is called ‘an invention’ of the dogmaticians,30 has a firm basis and support in Scripture. Every word of Scripture is an inviolable sanctuary, is the infallible, unchangeable Word of God. Scripture insists on that… . Scripture contains the earnest warning not to add to, nor to take away from, what God has commanded and spoken (Deut. 4:2; 12:32; Prov. 30:5-6; Rev. 22:18-19). Every addition is a sacrilege, since it dilutes God’s Word with the word of men. And the warning has the threat attached: ‘Add thou not unto His words, lest He reprove thee’ (Prov. 30:6)… . Christ raises His voice and declares: ‘I am not come to destroy, but to fulfill. For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the Law, till all be fulfilled. Whosoever therefore shall break one of these least commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven; but whosoever shall do and teach them, the same shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven.’ (Matt. 5:17-19.) Cp. Luke 16:17. We take Christ’s warning to heart and confess with Paul: ‘I believe all things which are written in the Law and in the Prophets’ (Acts 24:14).” Likewise Luther confesses: “The Scriptures have never erred” (St. L. XV:1481) and “One little point of doctrine is of more value than heaven and earth; and therefore we cannot abide to have the least jot thereof corrupted” (St. L. IX:650). The context shows that Luther has in mind every tittle of doctrine, inasmuch as the doctrine is expressed in the definite, inviolable words of Scripture. The point at issue over against the Sacramentarians was the words of the institution of the Lord’s Supper, and Luther adds: “If they believed that the Word is God’s, they would not play with it in such a manner, but would hold it in highest esteem and without any dispute or doubt regard it as credible, and would know that one word of God is all words of God and all words of God are one word of God.” Quenstedt has made statements with regard to the infallibility of the words of Scripture at which the camp of modern theologians throws up its hands in horror. And yet Quenstedt does not say one whit more than what the Scriptures say of themselves. He writes (Systema I, 112): “The canonical Holy Scriptures in the original text are the infallible truth and free from every error, or, in other words, in the canonical Holy Scriptures there is found no lie, no falsity, no error, whether in the things or in the words; but all things, and each single one, that are handed down in them are the most true, whether they pertain to doctrine or morals or history, chronology, topography, or nomenclature; no ignorance, no thoughtlessness or forgetfulness, no lapse of memory, can or dare be ascribed to the amanuenses of the Holy Ghost in their penning of the sacred writings.” Likewise Calov (Systema I, 551) says: “No error, even in unimportant matters, no lapse of memory, not to say untruth, can have place in the whole of Scripture.”

These words of Quenstedt and Calov have sounded so strange to even a man like Philippi that he felt constrained to express his dissent from them. He wrote in the first edition of his Kirchliche Glaubenslehre (I, 1st ed., p. 208 f.) that one should not at the outset exclude the possibility that some few minor discrepancies actually are present, that there is here a territory of unimportant accidents, just as the resemblance of a portrait does not depend on the exactly corresponding length of the fingernails or the hair, that the question how far inspiration has overcome human weakness can be decided not a priori, on the basis of what Scripture says of itself, but only a posteriori, on the basis of human investigation, and that “we therefore would not like to declare with Calov, at least not a priori: ‘No error, even in unimportant matters, no lapse of memory, … can have place in the whole of Scripture.’ ” But Philippi did not feel at ease in admitting this possibility of errors in unimportant details in Holy Scripture. He remarks that experience has shown it to be a rash assumption when in a concrete case this or that difference had been regarded as absolutely unsolvable, that (on page 197) the corrosive poison of subjectivism has eaten into the spiritual marrow and bone of faith to such a degree that it appears a trifling thing to us to break the objective, infallible, and eternal Word of God, that the truthfulness and certainty of the revelation of Scripture in no wise depends on the success of the attempts to harmonize Scripture and the natural sciences, so that the believing theologian should not rejoice so much when the scientific hypotheses agree with Scripture and not grieve so much when they do not agree: “The actually assured results do not contradict Scripture, and the hypotheses are but hypotheses.” One of the strongest indications of Philippi’s perplexity is this, that he felt impelled to make the senseless distinction between “Wortinspiration” and “Woerterinspiration” and was ready to accept the former and to reject the latter (pp. 184, 191) — a distinction which called forth much derision even among the neologists. But no sane person ever taught a “Woertennspiration,” least of all the Lutheran dogmaticians. Dr. Ebeling correctly remarks: ‘The Bible does not contain ‘Woerter’ (disconnected words) like a dictionary, but ‘Worte’ in a certain connection and sense.” 31 Philippi finally saw his error, and in the third edition of his dogmatics (3d ed., I, p. 279) he expressly retracted his former opinion that in minor matters an error is possible. These are his words: “I am now ready to admit that according to my own theory of inspiration even the possibility of errors in Scripture in minor matters and unimportant accidentals must be denied a priori.” Modern theologians were glad to take notice of Philippi’s former position. Thus Grimm wrote: “Philippi, if we correctly understand him, teaches that the manner and form of the diction, not, however, the single words, are due to the Holy Spirit [Wortinspiration, not Woerterinspiration]; also he concedes discrepancies of very slight importance in the narrations.”32 We do not find the same eagerness to report Philippi’s retraction, even after it had become known. In 1912 Nitzsch-Stephan still talks of Philippi as though there had been no change from his former position (Ev. Dogmatik, 3d ed., 1912, p. 253).

5. The inspiration of Scripture self-evidently includes also the impulse and command to write (impulsum et mandatum scribendi). When Roman theologians, on the one hand, are ready to admit that the Evangelists and Apostles wrote according to God’s will and by God’s inspiration (Deo volente et inspirante), but, on the other hand, claim that a command (mandatum) to write cannot be found, this claim amounts to a self-contradiction.33 Quenstedt correctly says: “They [the Roman theologians] are perpetrating a joke (nugantur).” If God willed that the Evangelists and Apostles should write and at the same time inspired what they wrote, this act of inspiration constituted also the impulse and command to write. The Lutheran theologians therefore say: “Inspiration itself, by which the things were suggested that were to be set down in writing, implies the impulse of executing the act of writing” (Baier-Walther, I, 99). Quenstedt (I, 96): “The inspiration of the things to be written and the inner impulse to write amount to the same thing. It involves a contradictio in adiecto to say that the Apostles wrote by the will and inspiration and suggestion of God and nevertheless not by His command.” The reason why the Roman theologians burden themselves with this self-contradiction is manifest. They bring this sacrificium intellectus in the interest of supreme authority of the Pope, ad summam papae potestatem stabiliendam. The claim that the Gospels and the Apostolic Epistles are indeed inspired, the inspired Word of God, but were not written by the express divine command, is meant to lower the value and necessity of the Holy Scriptures and, per contra, to exalt the value and necessity of the “unwritten Word of God,” which under the name of “tradition” is administered, controlled, and manufactured by the Pope (Luther: “the magician’s bag, Gauckelsack,” of the Pope). According to the Roman doctrine the written Word of God, Holy Scripture, is not a complete standard of faith and life, but needs to be supplemented by tradition, which is to be “received and to be venerated with an equal affection of piety and reverence.”34 The “equal affection of piety and reverence” naturally, however, changes into an unequal affection of piety and reverence, and tradition is to be placed above Scripture if the Evangelists and Apostles have written without a divine mandate. Then the matter assumes this aspect: The Holy Scriptures are really not a divine institution, since the mandatum scribendi is lacking. But the holy father Pope, as the visible head of the Church appointed by Christ, is a divine institution in the eminent sense, and thus the supreme authority in the Church rests in the Pope, respectively in the tradition controlled by the Pope. These views are expressed in such dicta of Romish theologians as the following: the Christian doctrine is preserved purer by tradition than by Holy Scripture; the Church could exist very well without Holy Scripture, but not without tradition; Christ did not want to make His Church dependent on a paper Scripture or a lifeless parchment; they went so far as to say that the Scriptures are, because of the human weaknesses clinging to them, not at all a dependable guide and the Church would have been served better if there had been no Scripture at all.35 This explains the interest Roman theologians have in denying the mandatum scribendi and in speaking as though the Evangelists had written merely “by accident,” “for accidental reasons,” etc. Their concern is to have the Ego of the Pope acknowledged as the supreme authority of the Church.

The close relation of modern theology to the theological principle of Rome will be seen at once. Although the modern theologians deny the inspiration of Holy Scripture, they are nevertheless ready to admit that God’s Word is in Scripture. Even radical neologists still concede that the Apostles in their writings “stand closer” to the divine revelation than the later generations. But what they strongly protest against, just like Rome, is that the divine revelation is to be restricted to the “book revelation” of Holy Scripture, to a “paper Pope,” to a codex of dogmas fallen from heaven. — Modern theology has the same interest as Rome. According to its own declaration it desires freedom from Scripture as the only source and standard of theology and in place of Scripture would make the decisive factor in the Church, indeed not the Ego of the Pope, but the “experience” or — what amounts to the same thing —“the pious self-consciousness,” the Ego of the theologizing subject. When Theodor Kaftan says: 36 “The modern theology that I stand for bows to no mere external authority,” he means by that “external authority” to which he will not bow Holy Scripture, the written Word of the Apostles and the Prophets. And when he adds that he bows to “God’s Word” “as to an authority that has proved itself, and maintains itself, in its own power,” he means to say that he will accept only so much of Scripture as valid as has given satisfactory proof of being the truth before the judgment seat of his “experience” or his “pious self-consciousness.” Ihmels means the same thing when he calls it a “fatal mistake” that the Early Church, the Church of the Reformation, and the old dogmaticians retreated into Scripture as the sole source and norm of the Christian doctrine and when he sees in Schleiermacher’s theology, and particularly in the Erlangen theology, an “immense advance” in the right direction, because this theology has brought to the fore the “experience” or the “Christian Ego.” (Zentralfragen, 2d ed., p. 56 ff.) What we get is this: Rome is concerned with the Ego of the Pope, modern theology is concerned with the Ego of the theologizing individual.

Scripture has already ended the whole dispute by stating that the Christian Church is built to no extent whatever upon the pious Ego whether of the Pope or of other theologizing individuals, but to the Day of Judgment is built solely on the foundation of the Apostles and Prophets, i. e., the Word of Scripture. We have already seen that Christ directs His Church and all the world to the Word of His Apostles, that the Apostles point to their written Word over against all spurious sources of knowledge and all spurious norms, that the Apostles knew that they had taught all of Christ’s Word, and that they accordingly instruct all Christians to deny Church fellowship to all who depart from the doctrine of the Apostles. We have also noted that the Apostles claimed not only temporary and local, but permanent validity for what they wrote, even when their writing was prompted “by accidental reasons” (1 Cor. 1:11). Luther discusses this point in dealing with a Roman opponent who would grant only temporary and local validity for the Lord’s Supper sub utraque specie; in this connection he insists most emphatically that the epistles of Paul are binding on all Christians, of all times, and of all places. He writes: “What could be more ridiculous and more worthy of this friar’s brain 37 than this saying that the Apostle wrote these words and gave this permission (namely, to celebrate the Lord’s Supper under both kinds) to a particular church, i. e., the Corinthian and not to the Church Universal? Where does he get his proof? Out of his usual storehouse, namely, out of his impious head. If we admit that any epistle, or any part of any epistle, of Paul does not apply to the Church Universal, then the whole authority of Paul falls to the ground. Then the Corinthians will say that what he teaches about faith in the Epistle to the Romans does not apply to them. What greater blasphemy and madness can be imagined than this? God forbid that there should be one jot or tittle in all of Paul which the whole Church Universal is not bound to follow and keep! Not so did the Fathers hold, down to these perilous times, in which, as Paul foretold, there would be blasphemers and blind and insensate men, of whom this brother is one, nay, the chief.” (St. L. XIX, 19 f.) 38