_6_On the History of the Doctrine of Inspiration

Christ and the Apostles taught the verbal inspiration both of the Old and the New Testament, a fact we have repeatedly demonstrated in defining Christian theology and particularly in the chapters “Holy Scripture Identical with the Word of God” and “The Verbal Inspiration of Holy Scripture.” Rothe, too, whom many regard as a leader in establishing the modern, the “correct,” view of Scripture (Nitzsch-Stephan, p. 255 ff.), admits that the Apostles identified Scripture and the Word of God — though he stands sufficiently far toward the left to confess openly that he does not accept the opinion of the Apostles as authoritative.76 When Hofmann, following Schleiermacher, claims in his Schriftbeweis, 2d ed., I, 671 ff., that Christ and the Apostles did not appeal to “single statements” or “individual words,” but always only to “the whole of Scripture” or “the organic whole of Scripture,” hence did not teach Verbal Inspiration, Kliefoth, as already stated, correctly calls this an “inconceivable concept.” Hofmann’s assertion belongs to the class of absolute dicta that nonplus one because of their boldness. Every reader of the Gospels and the Epistles of the Apostles knows that the opposite is the fact (Matt. 4:4, 7, 10; John 10:35, etc. – Rom. 4:3, 6, 7; Gal. 3:16, etc.).

The Church Fathers, too, taught the Verbal Inspiration. That is so evident that Cremer raises the charge that “they have the same doctrine of inspiration as the older Protestant dogmaticians” (R. E., 2d ed., VI, 751). Among recent theologians Rudelbach furnishes the same proof with regard to the Church Fathers, not in a spirit of criticism, however, but of approval and praise.77

Regarding Luther and the dogmaticians, modem theology generally acknowledges and deplores that they have “identified” Scripture with the Word of God, thus taking over an evil heritage from the ancient Church and, unfortunately, passing it on, to the harm of the Church. (Ihmels, Zentralfragen, 2d ed., 56 ff. See above.) In order to gain a particeps criminis in nuce in the Reformer of the Church, most modern theologians insist that one finds here and there in Luther a tendency toward a “more liberal conception of Scripture.” (Thus also R. Seeberg, Dogmengeschichte, II, 285 ff.) This assertion is in conflict with the historical facts, as the next chapter will show. As to the Symbols of the Lutheran Church, it is generally admitted in our day that they presuppose Verbal Inspiration as an unquestionably established doctrine, since they use “Scripture” and “Word of the Holy Ghost” as synonymous terms. Augsburg Confession: “Why does Scripture so often prohibit to make, and to listen to, traditions? … Did the Holy Ghost in vain forewarn of those things?” (Trigl. 91, 49.) Apology: “Do they think that these words fell inconsiderately from the Holy Ghost?” (Op. cit., 153, 108.) “They have condemned several articles contrary to the manifest Scripture of the Holy Ghost” (op. cit., 101, 9). When those Lutherans who deny inspiration find comfort in the fact that the Lutheran Symbols indeed presuppose Verbal Inspiration as an undeniable truth, but contain no separate article which teaches it, neither logic nor psychology shows how there can be any comfort for them in this observation. — It cannot be denied that among the Lutheran dogmaticians George Calixt (d. 1656) gave up the Scriptural doctrine of inspiration; he limited inspiration to the chief matters and the things not previously known to the holy writers; in minor matters and in the things previously known to them he assumed only a preservation from error (Quenstedt, I, 100). It must also be admitted that John Musaeus (d. 1681) on occasion voiced the opinion that Verbal Inspiration was a hypothesis not yet sufficiently proved. Musaeus retracted this statement and declared that it did not express his view but that of the opponents.78

When rationalism, which wielded a mighty influence after the middle of the 18th century, discarded the Christian doctrine in general, namely, the satisfactio Christi vicaria, it also discarded the inspiration of Holy Scripture.79 The denial of the satisfactio vicaria is a surrender of the differentia specifica of Christianity and puts the Christian religion in a class with the pagan religion of works. What need is there after that of a God-inspired Holy Scripture? The whole theological activity of the rationalists consists in proving that Scripture, correctly understood, that is, interpreted according to reason, is nothing more than a sublime code of morals, exemplified in Jesus of Nazareth. “The Reformer of the Church of the 19th Century,” Schleiermacher, did not, like the Reformer of the 16th century, lead theology back into Scripture, but into the morass of emotional rationalism. To him the source and determining norm of theology are no longer Scripture, but the pious self-consciousness of the theologizing subject, the Christian experience, etc. It is a fact admitted by all that the entire modern theology, liberal and conservative, practices theology according to the method of Schleiermacher, though there are differences among them as to what belongs to the “pious self-consciousness.” Because it has not returned to the Scripture doctrine of the vicarious satisfaction of Christ, modern theology stands outside the sphere within which the Word of Christ, which we have in the Scriptures of the Apostles and Prophets, is recognized as Christ’s, that is, God’s Word. Whoever will not believe what Christ and the Apostles teach of the reconciliation of the world by the substitutional satisfaction of Christ will naturally also not believe what Christ and the Apostles say of Holy Scripture. Whoever rejects God’s thoughts and entertains his own thoughts on Gods’ reconciliation of sinful mankind will naturally also entertain his own thoughts on God’s Word, Holy Scripture, even to the extent of rejecting what God says regarding Scripture.80

We might summarize the position of modern theologians toward Scripture in these words: modern theologians refuse to believe what Scripture says of itself, but would determine the character of Scripture a posteriori, by way of human investigation and criticism.81 Applying this modus procedendi they reach the conclusion that the Scriptures are not God’s infallible Word, but a report, more or less divinely influenced, on God’s revelation by word (account of the revelation). In this historical report, which originates in part with the Holy Ghost and in part with men (“Urgemeinde” — primitive Church, hence “divine-human” report), errors are naturally not excluded. Hence it is said to be the office of modern theology, which possesses in a high degree a sense of “reality,” to subject Scripture, in its contents and wording, to criticism, even though it has not yet succeeded in defining the boundaries between truth and error in the Bible. But as to the chief point they are agreed: Scripture cannot be regarded as God’s infallible Word; Scripture, if regarded as the infallible Word of God, cannot produce “warm-blooded” Christianity; the natural consequence of the old conception of Scripture is “intellectualism.” When the modern theologians still speak of “inspiration,” they do not mean the unique divine act by which He breathed His Word into the holy writers and made it the foundation of faith for His Church unto the Last Day (Eph. 2:20; John 17:20), but they take it to mean merely an intensified spiritual enlightenment of a kind which all Christians possess. As the illumination possessed by all Christians does not include perfect inerrancy, so neither did the intensified illumination of the holy writers make them inerrant.

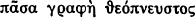

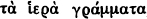

Another characteristic of modern theology is the claim of a majority of its representatives that “manifestly” degrees of the inspiration of Scripture must be assumed. But this assumption of degrees in inspiration has as little sense as the assumption of ranks in the Godhead. When the subordinationists call God’s Son God “in the secondary sense of the word,” they destroy the concept “God”; and when modern theologians speak of degrees of inspiration, they discard the Scriptural concept “inspiration.” Kahnis actually combines these two things, ranks in the Godhead and degrees in the divine inspiration of Holy Scripture. He assumes three degrees of inspiration, though he confesses not to be entirely sure of it. He writes (the quotation is given in Baier-Walther, I, p. 103): “Among these Prophetic and Apostolic writings we find differences, from the viewpoint of both origin and content. We cannot place Deuteronomy on the same level with the first four books. Among the Prophets, Obadiah and Jonah stand beneath Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. In the New Testament the Pastoral Epistles and the Epistle to Philemon stand in the second row. The word of revelation given within the kingdom of the Old and the New Covenant can be understood only in connection with its history. Accordingly the historical books of the Old and the New Covenant have their place in the canon, but only one of second rank. As their content is the combined activity of the divine and the human in the Kingdom of God, so also the sacred historical writers are not necessarily men who received revelations, but only men animated by the Spirit of the Kingdom of God. This class is made up in the Old Testament of the prophetic-historical books as of the first rank; the hagiographa Ruth, Ezra, Nehemiah as of the second rank; the books Esther and Chronicles as of the third rank. In the New Testament this second class includes the first three Gospels as of the first rank, the Acts of the Apostles as of the second rank. In the third class are the Old and New Testament hagiographa, the contents of which are neither revelation nor history of the Kingdom, but which depict the life in the Kingdom of God as it appears in the individuals. This class includes in the Old Testament the Psalms as of the first rank, the Proverbs of Solomon, Job, and the Lamentations of Jeremiah as of the second rank, the Song of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, and Daniel as of the third rank; in the New Testament the Epistle to the Hebrews and the Second and Third Epistles of John (which very probably but not positively are of Johannean origin and in addition are of a more personal nature) as of the first rank, the rest of the Catholic Epistles and the Apocalypse as of the second rank. While in the first class the person is of prime importance, the individual recedes in the second class, since here everything depends on the objective truth and the spirit in which things are presented. But it lies in the nature of the third class that here the subject becomes important. It is not immaterial whether a Psalm was written by David or not, whether the Proverbs were written by Solomon or others, whether Daniel is authentic or not, etc. But in the case of these Scriptures of the third rank one must guard well against giving authenticity too much weight. Faulty as this attempt to divide Scripture into three classes may be from the viewpoint of inspiration, nevertheless a distinction of degrees is in accordance with the sense of Scripture; it also has renowned authorities of ancient and modern times in its favor.” Manifestly this distinction is not in accordance with Scripture. Scripture says 2 Tim. 3:16  . This statement places all writings of the Old Testament (

. This statement places all writings of the Old Testament ( , v. 15) without any distinction into one class. Christ quotes John 10:34 from the Psalms (Ps.82:6; “Ye are gods”). But He does not add that this is a “third-class” word of Scripture, as Kahnis holds; rather He says: “The Scripture cannot be broken.”. This whole distinction of degrees of inspiration is a human fabrication, the purpose of which is to free the human theologizing subject from the irksome bond of the divine authority of Scripture.

, v. 15) without any distinction into one class. Christ quotes John 10:34 from the Psalms (Ps.82:6; “Ye are gods”). But He does not add that this is a “third-class” word of Scripture, as Kahnis holds; rather He says: “The Scripture cannot be broken.”. This whole distinction of degrees of inspiration is a human fabrication, the purpose of which is to free the human theologizing subject from the irksome bond of the divine authority of Scripture.

Sad to say, it is true what Nitzsch-Stephan says of the “present situation” (p. 258): “In our day the orthodox doctrine of inspiration has hardly any significance in dogmatics. It is, true enough, still being upheld by a few, e. g., Koelling and Noesgen, with some modifications… . The rest of the theologians, including the conservatives, reject the old doctrine.” Zoeckler mentions (Handbuch der theol. Wissenschaften, 2d ed., III, 149) as lonely defenders of the old doctrine: Kohlbruegge, Caussen, Kuyper, and, “among the Lutherans, Walther in St. Louis and with him the Missouri Synod.” Also most of the presentday Reformed theologians have given up the inspiration of Scripture.82 Well-known exceptions are Charles Hodge of Princeton; Wm. Shedd of Union Seminary, New York; Benj. B. Warfield of Princeton.83 Of the more widely known theologians in Germany it is only Philippi who in the last years of his life returned to the Scripture doctrine of inspiration.84

In the Roman Catholic Church some theologians of note have limited inspiration to the mysteries of faith or the chief matters; concerning other matters, however, they have assumed a mere preservation from error.85 A few others have gone further and expressly admitted the actual occurrence of errors.86

The Socinians and the Arminians assume errors in “minor matters.” 87 — This would be the place to advert to the essential agreement of the ancient and modern “enthusiasts,” the Quakers, and the like, with modern theology. Just like the modern theologians, the “enthusiasts” refuse, in the interest of their “inner life” or their “immediate revelation,” to “identify” Scripture with the Word of God. Their talk of “spirit,” of “inner light,” of “immediate revelation,” lies on the same plane as the talk of modern theologians about a “self-certainty” of Christianity and its religion, a certainty which does not depend on Holy Scripture, but “rests in itself and is immediate truth” (Erlangen theology). Again, when the “enthusiasts” declare the “spirit,” or the “inner light,” etc., to be the “chief source” or the “real source of the truth” and acknowledge Scripture only as a “subordinate norm,” this corresponds exactly to the position of modern theology, which likewise turns everything topsy-turvy in the Christian Church by casting aside Scripture as the source and norm of doctrine, withdrawing into the “pious self-consciousness” of the theologian, the “experience,” as constituting the allegedly “impregnable fortress,” and from this vantage point correcting Scripture.88

Calvin’s position toward Scripture has been also much debated in recent times. Seeberg says (Dogmengeschichte II, 385): “Calvin, then, is the creator of the so-called old dogmatical theory of inspiration”; and to prove his assertion, he shows that Calvin not only calls the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments God’s “oracles,” but also expressly states that the Scriptures, including the historical parts (historiae), were written dictante Spiritu Sancto (Inst. IV, 8, 6), and the holy writers were His amanuenses (Inst. IV, 8, 9). Seeberg also points to the fact that Calvin called the critics who asked: “How do we know that Moses and the Prophets wrote the books which now bear their name?” and who even dared to question whether there ever was a Moses, “nebulones” (miscreants) and their wisdom “insania” (Inst. I, 8, 9). Seeberg declares that he does not agree with Heppe, who says (Die Dogmatik der ev.-ref. Kirche, 1861, p. 16 f.): “There is [here in Calvin] no thought of a real inspiration of the recording.” — It will have to be admitted, however, that Calvin, contradicting his direct statements that Scripture is written dictante Spiritu Sancto and that the holy writers must be called Spiritus Sancti amanuenses, occasionally speaks of the Evangelists as incorrectly quoting from the Old Testament.89 Here, then, there is an inconsistency on the part of Calvin.

And, what is worse, it has little practical value when the older and the more recent Calvinists (Hodge, Shedd, Boehl, etc.) teach Verbal Inspiration and at the same time teach the doctrine peculiar to Calvinism. Calvinism teaches that the redemption which is in Christ Jesus does not extend over all men, but only over a part of mankind. It teaches with Calvin that the purpose of the written Word is not to lead all men to faith and salvation, but to harden the hearts of the majority of the hearers. Calvin teaches (Inst. III, 24, 12): “Those, therefore, whom He has created to a life of shame and a death of destruction, that they might be the instruments of His wrath and examples of His severity, He causes to reach their appointed end, sometimes depriving them of the opportunity of hearing the Word, sometimes, by the preaching of it, increasing their blindness and stupidity.” Furthermore, the old and the more recent Calvinists teach that those who are actually illuminated unto faith and salvation do not receive this illumination through the external Word, the Scriptures, but receive it without this Word, through an immediate illumination of the Holy Ghost. It is obvious that such teaching makes the truth that Scripture is God’s inspired Word entirely worthless for practical purposes. Calvinists must become, as has been pointed out by men in their own midst, Lutherans in practice, that is, they must forget their gratia particularis and their immediata Spintus Sancti operatio if, terrified by the Law, they desire to derive any consolation from the written Word as the Word of God. And the grace of God leads many a Calvinist to forget his Calvinism in the time of need.90

The synergists, too — those that still teach the inspiration of Scripture—make this doctrine practically worthless. Because the synergists make the obtaining of God’s grace dependent on an achievement of man (self-decision, self-determination, “different conduct,” lesser guilt in comparison with others), and because this required achievement is found in no man (Rom. 3:19: “That all the world become guilty before God”; v. 22: “There is no difference”), by their obstruction of the sola gratia raise as strong a barrier against the obtaining of God’s grace as do the Calvinists by their obstruction of the universalis gratia. The Christian faith which is counted by God for righteousness is convinced that God “justifieth the ungodly” (Rom. 4:5). Whoever considers himself as being better before God, or less guilty than other men, is eo ipso excluding himself from grace (Luke 18:9-14; Rom. 11:22). A synergist can be saved, just like the Calvinist, only if he becomes inconsistent. As the Calvinists must forget their limitation of the universalis gratia, so the synergists must forget their limitation of the sola gratia if the truth that the Scriptures are God’s own Word is to be of any practical value for them. And here, too, this forgetting, no doubt, occurs in many instances. It is solely the grace of God which saves from an error which is fatal in itself.91

It goes without saying that the Romish theologians, too, completely destroy the practical value of their profession of the inspiration of Scripture by assigning the authoritative interpretation of Scripture to the Pope. The result of this exegetical method is that it is no longer God who through His Word, the Holy Scriptures, speaks to men, instructs, and rules them, but that the Pope — pretending to speak in the name of Scripture — subjects the Church and the State to his papal Ego. Luther is right in declaring that the principle of the “Romanists” that “the interpretation of Scripture belongs to no one except the Pope” is one of the “three walls” behind which the Papacy has entrenched itself and seeks to set up and maintain its rule. (An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation, St. L. X:269 f.)