_5_The Cause of the Divisions Within Visible Christendom

It is nothing strange that the non-Christian religions, which seek to reconcile God through human works, appear in well-nigh countless and diverse forms. For these works do not bring peace to the Conscience, and the inevitable result is that men keep on devising new works and new forms of worship. That accounts, say the Lutheran Confessions, for the multiplicity and diversity of the religions of the Law. The Apology states: “And because no works pacify the conscience, new works, in addition to God’s commands, were from time to time devised” (Trigl. 177, 87).

But it is a strange thing that diversities and divisions should appear within Christendom. For the Christian Church has only one principle of cognition, namely, the Word of Christ, given by Christ to the Church through His Apostles and Prophets,31 only one source of the saving knowledge, therefore only one doctrine, one faith. Moreover, this Word of Christ rejects and condemns in the strongest terms the causes of divisions, namely, the religion of works (Gal. 2:16: “By the works of the Law shall no flesh be justified”; 3:10: “As many as are of the works of the Law are under the curse”), and, on the other hand, teaches most clearly that remission of sins is obtained without the works of the Law, by faith in Christ, whose redemptive work has fully and completely reconciled God with the world (Rom. 3:28: “A man is justified by faith without the deeds of the Law”; Gal. 2:16: “Knowing that a man is not justified by the works of the Law, but by the faith of Jesus Christ”). Furthermore, all Christians experience that faith in the reconciliation accomplished by Christ brings peace to the conscience. “Therefore being justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” (Rom. 5:1). “We are complete in Him [Christ]” (Col. 2:10). Christians therefore have no need to look about for other means of reconciliation. Finally, Scripture expressly prohibits factions within the Church (“that there be no divisions among you,” 1 Cor. 1:10). In view of this, one would certainly expect to find the Christian Church to be free from divisions and factions.

History, however, presents an entirely different picture. Already in the days of the Apostles the Church was troubled with divisions.

What, then, causes the divisions in the Church? They are not the result of climatic influences, as some say, nor of racial differences, as others say.32 They are due solely to the fact that men arose within the Church and gained a following who did not continue in the Word of Christ’s Apostles and Prophets, but proclaimed their own word and as a natural consequence impaired, or even wiped out, the differentia specifica of the Christian religion, justification by faith, without the deeds of the Law. Divisions in the Apostolic Church arose because men refused to recognize the Word of the Apostles as the Word of God and offered the Church in place of the Word of God their own human notions. That is clearly stated by Paul in Rom. 16:17: “Now I beseech you, brethren, mark them which cause divisions and offenses contrary to the doctrine which ye have learned; and avoid them.” In the church at Corinth men engaged in the same business. They regarded themselves as “prophets” and “spiritual,” but in spite of this, rather for this very reason, they denied the divine authority of the Word of the Apostles and thus compelled Paul to utter the strong words: “If any man think himself to be a prophet, or spiritual, let him acknowledge that the things that I write unto you are the commandments of the Lord” (1 Cor. 14:37). At the same time these men made it their business to supplant the doctrine of salvation by grace with the religion of works. That is evident from the words in which Paul expresses his amazement over the apostasy of the Galatians: “I marvel that ye are so soon removed from Him that called you into the grace of Christ unto another Gospel” (Gal. 1:6), and from his sharp polemics against the advocates of the gospel of works: “Though we, or an angel from heaven, preach any other gospel unto you … let him be accursed” (1:8), and: “I would they were even cut off which trouble you” (5:12). The attempt to get rid of the Word of the Apostles and of the central teaching of Christianity, the doctrine of salvation by grace, has been and still is the sole cause of the divisions in the Christian Church.

This will become evident as we examine the formal and the material principle of the major divisions that disrupt the Church today, the Roman Catholic body, the Reformed communions, the factions within the Lutheran Church, and the modernistic schools. — We here submit in a condensed form what will be more fully presented when we discuss the individual doctrines in detail, thetically and antithetically.33

1. The Roman Catholic body, the largest in Christendom, acknowledges in principle the divine authority of Scripture. But it sets Scripture aside by insisting that its sense can be ascertained only through the interpretation given by the Roman Catholic Church, the sancta mater ecclesia, that is, in the last analysis, by the Pope. “It (the holy and sacred synod) decrees that no one, relying on his own skill, shall in matters of faith and of morals pertaining to the edification of Christian doctrine, wresting the sacred Scripture to his own senses, presume to interpret the Sacred Scripture contrary to that sense which holy mother church, whose it is to judge of the true sense and interpretation of Holy Scripture, hath held and doth hold.” (Tridentinum, Sess. IV, Decretum de editione et usu sacrorum librorum.) The inevitable result of thus interpreting Scripture according to the sense of “holy mother church,” that is to say, of the Pope, is that the Romish Church expressly and emphatically anathematizes the central doctrine of the Christian religion, the doctrine of justification by faith in the Gospel of grace without the deeds of the Law.34 There are indeed Christians among Roman Catholics, for there are those who in spiritual distress cast aside their good works and, in spite of the interdict of “the Church,” put their trust solely in the grace of God in Christ and are true members of the Holy Christian Church.35 Nevertheless, the fact remains that the Roman Catholic Church as such is a separate body destructive of true Christianity, because, in the first place, its formal principle is unchristian. By making the decrees of sancta mater ecclesia, that is, of the Pope, the source and basis of religious knowledge it suppresses the Word of Christ, the Word of the Prophets and Apostles, Holy Scripture. Luther gives an exact description of the situation when he says in the Smalcald Articles: “The Pope boasts that all rights exist in the shrine of his heart, and whatever he decides and commands with (in) his church is spirit and right, even though it is above and contrary to Scripture and the spoken Word” (Trigl. 495, 4). Secondly, its material principle is unchristian, for in thus setting aside Scripture, Roman Catholicism in fact proscribes the Christian doctrine of grace. The whole colossal machinery of Romanism is geared to establish the absolute authority of the Pope and to serve the religion of works. Remove these two factors, and the Romish group would disappear from visible Christendom.

2. The Reformed denominations likewise acknowledge in principle the divine authority of the divinely inspired Scriptures. The inspiration of Scripture has found valiant champions among the Reformed theologians not only in the past, but also today.36 But in practice Reformed theology forsakes the Scripture principle. It has become the fashion to say that the difference between the Reformed and the Lutheran Church consists in this, that the Reformed Church “more exclusively” makes Scripture the source of the Christian doctrine, while the Lutheran Church, being more deeply “rooted in the past” and of a more “conservative” nature, accepts not only Scripture, but also tradition as authoritative.37 But this is not in accord with the facts. The history of dogma tells this story: In those doctrines in which it differs from the Lutheran Church and for the sake of which it has established itself as a separate body within visible Christendom, the Reformed Church, as far as it follows in the footsteps of Zwingli and Calvin, sets aside the Scripture principle and operates instead with rationalistic axioms. The Reformed theologians frankly state that reason must have a voice in determining Christian doctrine.

a. Rationalistic considerations have produced, first, the Reformed doctrine of the means of grace. While Scripture teaches that God offers and gives the forgiveness of sins which Christ gained and creates and sustains faith through external means ordained by Him (the Word of the Gospel, Baptism, and the Lord’s Supper),38 Zwingli and Calvin argue that it does not befit the Holy Ghost to make use of external means for the revelation and operation of His grace, that He does not need such external means, and that He does not, in fact, use them where His saving grace operates.39 Modern Calvinists take the same position. And this “holy spirit,” which severed the Holy Spirit from the means of grace, caused the division in the Protestant camp at the time of the Reformation; it raised the charge against Luther that he did not understand the Gospel, for by his clinging to the means of grace he showed that he was still in “the flesh.”40

Separating the revelation and operation of grace from the means of grace is, in effect, a reversion to the Romish “infused grace” (gratia infusa) and therefore a defection from the Christian doctrine of justification. For when men set aside the external means of grace, they can no longer base their confidence in God on God’s gracious disposition (favor Dei propter Christum), i.e., on the forgiveness of sin for Christ’s sake, which the grace of God offers in the Gospel promise and which is to be believed on the basis of this objective promise and offer; they necessarily base their confidence in God on an inward transformation, illumination, and renewal, which allegedly is effected by an immediate operation. This reduces grace in the final analysis to a good quality in man. Since the Holy Ghost will not deal in such immediate operations, all those who follow Zwingli’s and Calvin’s instructions and seek an immediate illumination and renewal necessarily substitute for the genuine operation of the Spirit their own human product. — Luther said repeatedly: “Papist and ‘enthusiast’ are one.” That judgment was not an outburst of “the immoderate polemics in the 16th century,” but is based on facts.

The fact that despite the Reformed repudiation of the means of grace many Christians are found in the Reformed denominations is due to an inconsistency, to which Luther points frequently, particularly in the Smalcald Articles. If the Reformed would translate their theory concerning the supposed immediate operation of the Spirit into practice, they would have to refrain from proclaiming the Gospel by the printed or spoken word and keep silence lest they interfere with the operation of the Spirit. But they refuse to do this, and in as far as they teach the Gospel of the Savior crucified for the sins of the world, they give the Holy Ghost the opportunity to create and sustain faith in Christ, not without the Word and alongside the Word, but through the Word, mediately.

b. Again, when the Reformed deny the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Lord’s Supper, they are repudiating the Word of God because of rationalistic considerations. They admit, directly and indirectly, that the Scriptural statements on the Lord’s Supper indicate prima facie not the absence, but the presence of the body and blood of Christ. But, they say, the words of institution must be so interpreted that they agree with “faith.” And when they are asked what this “faith” is which must interpret Scripture, the Reformed theologians of all times do not adduce Scripture but a rationalistic axiom. They insist that since every human body occupies space and is visible, the body of Christ, too, can have only a visible and local mode of presence (visibilis et localis praesentia); else it would not be a true human body. The presence of Christ’s human nature, says Calvin, cannot extend beyond the natural dimensions of the body of Christ (dimensio corporis, mensura corporis), beyond about six feet, and consequently cannot suffice for the simultaneous celebration of the Lord’s Supper at many places in the world. Carlstadt and Zwingli, and Calvin, too, deny the Real Presence, clearly taught in the words of institution, on the strength of the rationalistic canon that wherever the body of Christ is, it must necessarily occupy space and be visible.41 The Reformed denial of the Real Presence is thus based not on what Scripture says, but on what reason dictates; a human judgment counts more than the Scripture statement. Calvin accepts Luther’s definition of the status controversiae:” Their whole case rests on this, that Christ’s body must be at one place only, in a local and tangible manner.” The motive for the Reformed denial of the Real Presence is fully discussed in Vol. III.

c. The false principle, both the formal and the material, of the Calvinistic theologians is evident particularly in their answer to the question: Is the grace of God in Christ universal (gratia universalis) or particular (gratia particularis)? The Calvinistic Reformed will not permit Scripture to answer the question, though in many passages it teaches the gratia universalis (John 1:29; 3:16 ff.; 1 John 2:2; 1 Tim. 2:4-6, etc.); they find the answer in the historical “result” or the historical “experience.” Hodge: “We must assume that the result is the interpretation of the purposes of God” (Syst. Theol. II, 323).42 The Reformed argue: Since actually not all men are saved, we must conclude that Christ’s merit and God’s will of grace do not extend over all men; to say that God wills something (the salvation of all men) which is only partially accomplished is to make sport of God’s wisdom, power, and majesty.43 The rationalistic conclusions nullify the declarations of Scripture.

In a very pronounced way Calvin rejects the Scripture principle in favor of speculative rationalism when he denies that Matt. 23:37, Luke 19:41 ff., Is. 65:2, and Rom. 10:21 prove that God seriously wills the salvation of all. It would be ridiculous, he contends, to take seriously the plaint and tears of Jesus and the “hands stretched forth” to the people and thus to “transfer to God what is peculiar to man.” (Inst. III, ch. 24, 17.) It will be seen that Calvin is so obsessed with his rationalistic speculations about the absolute God that he becomes the bitter enemy of all Scripture statements that teach universal grace.

The inevitable result of eliminating the gratia universalis is that the Gospel is, in effect, paralyzed. The stricken sinner does not believe in the Savior of sinners if he is really convinced that Jesus is the Savior of only some of the sinners (gratia particularis). The children of God within the Calvinistic Reformed Church rejoice in the salvation gained for them by Christ only because they never believed in the gratia particularis; or if they have accepted it intellectually, they comfort themselves in the terrores conscientiae with the gratia universalis. — When Reformed theologians, contrary to their own principle, direct the despairing sinner to the gratia universalis, they themselves condemn their partisanship for the gratia particularis.44

The Arminian section of the Reformed Church makes much of the gratia universalis, but does so at the expense of the sola gratia. Arminianism stands for a human co-operation in conversion.45 But in thus “limiting” the sola gratia it has abandoned the Scripture principle, for Scripture ascribes the conversion and salvation of man to the monergism of God (Eph. 1:19: “who believe according to the working of His mighty power”; Phil. 1:29; 1 Cor. 2:14; 1:23).46— At the same time this Arminian faith, which is in part the work of man, strikes at the heart of the Christian doctrine of justification  , without the Law, not by works. When Erasmus declared that the facultas se applicandi ad gratiam, the co-operation of man, is needed to bring about conversion, Luther said: “Du bist mir an die Kehle gefahren” (“iugulum petisti,” “you have me by the throat”), “You have attacked the vital part at once” (St. Louis XVIII: 1967. Opp. v. a. VII, 367).

, without the Law, not by works. When Erasmus declared that the facultas se applicandi ad gratiam, the co-operation of man, is needed to bring about conversion, Luther said: “Du bist mir an die Kehle gefahren” (“iugulum petisti,” “you have me by the throat”), “You have attacked the vital part at once” (St. Louis XVIII: 1967. Opp. v. a. VII, 367).

3. This criticism applies, of course, also to the synergistic Lutherans. Synergism teaches that man’s conversion and salvation depend on his “right conduct,” “self-assertion,” “self-determination,” “lesser guilt in comparison with others,” etc. — that is the same as the Arminian “co-operation” — and thus blocks the entrance of saving faith into the heart. Faith finds entrance only in crushed hearts,47 and it is the very nature of the Christian faith to rest on the sola gratia.48 A consistent synergist cannot be a believer. Those synergists who really believe in the sola gratia do so because in their private prayer life they do not believe their own doctrine. Frank is certainly right in maintaining that Melanchthon never really believed his synergistic theory.49 But that cannot undo the evil effects of his synergistic teaching. From his day to the present, synergism has been creating factions and divisions in the Christian Church.

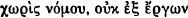

4. At the present time the dissensions and divisions outside and within the visible Church are due to the brazen denial of the divine authority of Scripture on the part of most of the leading theologians. Denying that Holy Scripture is Cod’s own infallible Word, these men naturally discard Scripture as the sole source and norm of the Christian doctrine, and thus they eo ipso do away with the principle of unity in the Christian Church. The unity of the Church is a unity in the truth, but only those know the truth who continue in the Word of Christ (John 8:31-32). And as Paul, Christ’s Apostle, assures us, he who does not consent to the wholesome words of our Lord Jesus Christ “is proud, knowing nothing” (1 Tim. 6:3 ff.). But our modern theologians, the so-called “positive” theologians no less than the liberals, refuse to accept Scripture as the principle of knowledge, the source and norm of doctrine (formal principle), substituting for it the “experience,” or “Erlebnis,” of the “theologizing individual,” also called “faith consciousness,” “Christian consciousness,” the “regenerate I,” etc. Concerning this theological method there is great unanimity. But it cannot produce unity in the Christian Church. — Nitzsch-Stephan declares that no one bases his dogmatics on the norma normans, the Bible, as was the fashion among the Old Protestants (Eν. Dogm., p. 15). But there the unanimity ends. “In the application of these principles,” the same writer tells us (op. cit., p. IX), “there are uncounted divergencies, these divergencies being due to the differences in the religious individualities of the dogmaticians or in the degree of their scientific consistency.” But at one point the moderns meet again. As with great unanimity they have discarded Holy Scripture as the only source and standard of the Christian doctrine, so with great unanimity they repudiate the Scripture doctrine of the satisfactio vicaria and so necessarily also the Scripture doctrine of justification by faith, “without the deeds of the Law” ( ).50

).50

The question arises here whether the Christian faith can exist side by side with the refusal to accept Scripture as the Word of God and with the denial of the satisfactio vicaria. The answer is: No — not if men reduce their teaching to practice. If men refuse to believe Christ and His Apostles when they declare that Scripture is the inviolable Word of God (John 10:35: “The Scripture cannot be broken”; 2 Tim. 3:16: “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God”; 1 Pet. 1:10-12), will they not also, to remain consistent, refuse to believe what Christ and His Apostles teach concerning the Saviorship of Christ (John 3:16; Matt. 20:28: “give His life a ransom for many”; John 1:29; 1 John 1:9; Rom. 3:28; etc.)? It can happen, however, and it has happened, that a person who in theory has denied the inspiration of Scripture and the vicarious satisfaction of Christ does by faith accept the remission of his sins in the hour of affliction and in the agony of death — basing his faith on the Word of Scripture and on the vicarious atonement of Christ. But thereby he relinquishes and disavows his former sectarian belief, by which he had separated himself from the Church, and returns to the one faith of the Christian Church, which continues in the words of Christ and knows of no other foundation for the assurance of God’s grace than the redemption ( ) wrought by Christ Jesus.

) wrought by Christ Jesus.

As our examination of the major divisions in the Church has shown, there is but one cause of the divisions within the visible Church: the refusal to abide by Scripture as the only source and standard of Christian doctrine and, in consequence of this, substitution, in one form or another, of the doctrine of works for the Christian doctrine of salvation by grace.

At this point we must answer the question whether the Lutheran Church should be numbered with the “divisions,” “factions,” “sects.” There are those who insist that the Lutheran Church is a sect like all the others. The discussion of this matter will have no point until we are agreed on the meaning of the terms “Lutheran Church” and “sect.” By “Lutheran Church” we do not mean all church bodies that call themselves Lutheran, but only those that actually teach and confess the Lutheran doctrine as it is taught and confessed in the Confessions of the Lutheran Church. And by “sects” we mean church bodies which have established themselves as separate organizations on the basis of unscriptural doctrines. The terms being thus understood, the Lutheran Church is certainly not a sect, since it does not stand for doctrines of its own, but simply confesses and teaches that which according to God’s will and order all Christians should confess and teach. This is the ecumenical character of the Church of the Reformation. On the one hand, the Lutheran Church does not set itself up as the una sancta, but acknowledges that there are children of God also in those denominations in which, besides the doctrines of men, enough Gospel is still proclaimed to produce faith in Christ as the only Redeemer. On the other hand, the Lutheran Church claims to be the Church of the pure doctrine, i. e., it claims that its doctrine agrees in all points with Holy Scripture and should according to God’s will be believed and accepted by all. The proof for this ecumenical character of the Lutheran Church, of course, must and can be furnished by way of induction, by submitting every one of its doctrines to the test of Scripture. Luther followed that method. In his confession of faith of 1529 he says: “If after my death anyone should say: ‘If Dr. Luther were living now, he would hold this or that article differently, for he did not sufficiently consider it,’ against this I say now as then, and then as now, that, by God’s grace, I have most diligently compared all these articles with the Scriptures time and again and often gone over them, and would defend them as confidently as I have now defended the Sacrament of the Altar.” 51

We should here like to call attention to the fact that the Lutheran Church has proved its unwavering adherence to the sola Scriptura in a matter in which the great majority of theologians from Augustine down to our day have under the stress of rationalistic considerations abandoned the Scripture principle. We refer to what is known as the crux theologorum. The question: Are you willing to maintain both the universalis gratia and the sola gratia? forces men to disclose whether Scripture or reason rules their theology. The Calvinists cannot pass this final examination. They insist, as we have seen, that if the is to be saved, the gratia universalis must be sacrificed. And the synergists, too, fail in this final test; they demand that in order to save the gratia universalis, the sola gratia must be surrendered. Both, says reason, cannot be maintained at the same time. The Lutheran Church is fully conscious of the difficulty which the human mind here encounters. But our Church maintains both the universalis gratia and the sola gratia, fully and without any restrictions, because both doctrines are clearly revealed in Scripture. It leaves the intellectual difficulty unsolved for the present; it awaits the solution in yonder life.52

The divisions and factions in the Christian Church are the result of a departure from Scripture doctrine. It is only natural to seek the underlying causes for this abnormal condition. Modern theologians of all shades not only assume a number of noble motives, such as the quest for truth, the scientific spirit, for the deviation from the Scripture doctrine and the incident formation of sects, but even assert that “these divergent trends have been designed by God and are beneficial to the Church.” But Scripture states the very opposite and states it most emphatically: that the motives actuating those responsible for this abnormal phenomenon in Christendom are carnal, not noble. As it often and earnestly warns against departing from the doctrine of the Apostles, which is Christ’s own doctrine (Rom. 16:17: “Mark them which cause divisions … and avoid them”), so it spares no words in condemning the motives behind this sorry business. Those who depart from the teaching of Christ and the Apostles are actuated by self-interest (Rom. 16:18: “They that are such serve not our Lord Jesus Christ, but their own belly”) as it shows itself in self-conceit (1 Tim. 6:3 f.: “He is proud”; R. V., “puffed up”); greed for honor (John 5:44); refusal to bear the cross (Gal. 6:12); envy (Matt. 27:18). Nor is it complimentary when Scripture uses the term “ignorance” in this connection (1 Tim. 6:4: “knowing nothing”; John 16:3; 1 Tim. 1:13). — Church history confirms this judgment of Scripture. Novatian would hardly have originated Novatianism and the Novatian schism if he, and not Cornelius, had been elected bishop of Rome.53 And one reason why Zwingli claimed to be the Reformer independent of, and in opposition to, Luther may have been jealousy of Luther’s leading position; Luther, he said, is only “one honest Ajax or Diomedes among many Nestors, Ulysseses, Meneläuses.” (See St. L. XX: 1134.)

It does not go beyond the province of a dogmatics if we point out very emphatically that the evil disposition which impels men to depart from Scripture and to create divisions, as exemplified by Novatian, Zwingli, and the founders of sects in the Apostolic period, inheres in every one of us and is ever active. Carnal ambition, envy, personal likes and dislikes, are continually threatening to cause factions and divisions in the local churches, in the synods, and in the church federations. Multae in ecclesia haereses ortae sunt tantum odio doctorum (Apol., Trigl., 186, 121). It is clear, therefore, that the unity in the Christian doctrine is in no wise the result of our power, wisdom, and skill; the grace and power of God alone can establish and preserve it. That is what Scripture states (John 17:11, 12, 15, 20, 21; Ps. 86:11, etc.) and what the Church confesses in the liturgy.54