_21_The Attainment of Theological Aptitude

Luther writes in the preface to the first part of his German books in 1539 (St. L. XIV:434 ff.): “Let me show you a right method for studying theology, the one that I have used. If you adopt it, you will become so learned that if it were necessary, you yourself would be qualified to produce books just as good as those of the Fathers and the church councils. Even as I dare to be so bold in God as to pride myself, without arrogance or lying, as not being greatly behind some of the Fathers in the matter of making books; as to my life, I am far from being their equal.254 This method is the one which the pious king David teaches in the 119th Psalm and which, no doubt, was practiced by all the Patriarchs and Prophets. In the 119th Psalm you will find three rules, which are abundantly expounded throughout the entire Psalm. They are called: Oratio, Meditatio, Tentatio.” Matthias Hafenreffer, professor of theology and chancellor of the university of Tuebingen (d. 1619), places this axiom of Luther at the head of his dogmatics,255 at the same time expanding it on the basis of Scripture and applying it to conditions of his day. Among the theologians of the last century Rudelbach (d. 1862) had this to say in an address on Luther’s instruction as to the study of theology: “You are familiar with the great word of Luther: Oratio, meditatio, tentatio faciunt theologum. This word comprises our entire theological methodology. Here, just as is the case with every thought sealed by the Spirit of God, there is nothing to add, nothing to subtract.” 256 There can be no doubt that the distressing lack of true teachers would be quickly ended if Luther’s methodology were observed everywhere.

Luther explains the necessity of the oratio thus: “First, you should know that Holy Scripture is a book such as will make the wisdom of all other books appear as folly, since no book teaches anything concerning eternal life but this one alone. Therefore you should straightway despair of your own wit and intellect, for with them you will attain nothing, but by such arrogance you will cast yourself and others with you from heaven into the abyss of hell, as happened to Lucifer. But enter into thy closet and kneel down and implore God with all humility and earnestness that by His dear Son He would grant you His Holy Ghost, who will enlighten you, guide you, and give you understanding. As you observe that David in the 119th Psalm continually prays: Teach me, O Lord, make me to understand, guide me, show me! and many more such words, though he knew well the text of Moses and of many more such books, also daily heard and read them; still he wants to have the true Master of the Scripture at his side in order that he may not plunge into them with his reason and become master himself. For that is what turns men into unruly fanatics who imagine that Scripture is subject to them and easily attained by their reason, as though it were the fables of Marcolfus or Aesop, for which they need no Holy Ghost nor prayer.” What Luther here says of the need of prayer rests on the conviction wrought by the Holy Ghost that there is no other book in the world like Holy Scripture. It is God’s own majestic Word. For that reason it is the only book which teaches eternal life, since all the world is held captive in the opinio legis. When other books do teach of eternal life, namely, teach that salvation is obtained without the works of the Law, by faith in Christ’s satisfactio vicaria, this is derived from Scripture. And since Scripture is the very Word of God, it is proper for the theologian that as often as he opens Scripture, he put no faith whatever in his wit or intellect and ask from God His Holy Spirit, who alone teaches one to understand God’s Word and creates that spirit which subjects itself to the Scriptures. Without this operation of the Holy Spirit man will arrogantly deem himself superior to Scripture, will make Scripture not the object of his faith, but of his criticism, an arrogance that will finally lead himself and others into perdition and will cause factions and divisions in the Church. And this is true of modern theology, because it will not accept Scripture as the Word of God, but places itself above Scripture. The Ego of the theologian becomes the dominating factor, and since there is many an Ego, the result is not unity in the Christian doctrine, but hopeless dissension and factionalism.

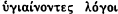

Of the meditatio Luther says: “Secondly, you should meditate, that is, not in the heart alone, but also externally, work on and ply the oral speech and the lettered words in the Book, read them and re-read them again and again, noting carefully and reflecting upon what the Holy Ghost means by these words. And have a care that you do not tire of it or think it enough if you have read, heard, said it once or twice and now profoundly understand it all. For in that manner a person will never become much of a theologian. He will be like worm-eaten fruit that drops from the tree before it is half ripe. Therefore you see in this Psalm how David over and over glories in the fact that he will speak, compose, declare, sing, hear, read, day and night and evermore; however, nothing but the Word and precepts of God alone. For God will not give you His Holy Spirit except through the external Word; be guided by that. For He has not without purpose commanded to put things down in writing, to preach, read, hear, sing, recite, etc.” In this exposition of the meditatio Luther tells what constitutes the study of theology, namely, not the meditation of what the theologizing Ego speculates about God and divine things, but the reflection upon what the Holy Ghost means and teaches in “the lettered words in the Book,” in the letters of Scripture, which is not the word of man, but the Word of the Holy Ghost. Modern theology, however, holds that Luther’s method demands a theology which is unworthy of theology and leads to intellectualism which is detrimental to piety. But the only method is the continual occupation with the “lettered words in the Book.” Without this method a person will “never become much of a theologian.” Luther wants no “rustication of the pastor,” as Walther used to say, but continued diligent study on his part.

Luther’s explanation of the tentatio reads thus: “Thirdly, there is tentatio, affliction. This is the touchstone; this teaches you not merely to know and understand, but also to experience how right, how true, how sweet, how lovely, how mighty, how consoling, God’s Word is, wisdom above all wisdom. That is why you observe how David in the 119th Psalm so often complains about all sorts of enemies, about nefarious princes and tyrants, about false prophets and factions, whom he must endure because he meditates, that is, as stated, is occupied with, God’s Word in every way. For as soon as the Word of God blooms forth through you, the devil will visit you, make a real doctor of you, and by his affliction will teach you to seek and love God’s Word. For I myself — if I may refer to my humble example (dass ich Maeusedreck auch mich mit unter den Pfeffer menge) — owe very much to my Papists, because through the raging of the devil they have so buffeted, distressed, and terrified me that they have made me a fairly good theologian, which I would not have become without them. And what they have, in turn, gained from me, they are heartily welcome to that honor, victory, and triumph, for they were bound to have it so.” Luther’s entire theology grew out of the tentatio, tentatio from within and from without. First came the tentatio from within. After years of uncertainty and terrors of conscience under the Roman doctrine of works God led him to an understanding of the Gospel of the free grace of God in Christ. Thus he tasted in his own heart and conscience “how right, how true, how sweet, how lovely, how mighty, how consoling, God’s Word is, Wisdom above all wisdom.” Then came the tentatio from without. When Luther taught the Word of God, the Papacy, yes, most all the world, got in his way and declared his eternal life as well as his temporal life forfeited. In this affliction he learned “to seek and to love God’s Word,” and this with such success that he could exclaim: “Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise.” Thus, by way of affliction, Luther became “a fairly good theologian.” And let us not be deceived! Also in our day the theological aptitude is attained in no other way than this, that in the distress coming from within and without we are driven into the Word of Scripture and cling to it as the only immovable divine force in the universe. The entire recent scientific theology has a different spirit. It does not employ God’s Gospel to bring peace to consciences stricken by God’s Law; it does not suppress the wisdom of the world with God’s Word, “the Wisdom above all wisdom.” It sees its task in satisfying the “craving of the intellect” and in harmonizing the Christian doctrine with the “scientific world view.”

Finally, Luther describes how continuance in the Word of Scripture creates those attitudes which are essential for the theologian, namely, grateful delight in the written Word, serene confidence in his ability to teach young and old in all stations of life, lasting and increasing humility to check the pernicious, ever-menacing pride which causes so much havoc in man’s own soul and among others. Luther closes thus: “Behold, here you have David’s rule. If you now will study well according to this example, you will also sing and glory with him, ‘The Law of Thy mouth is better unto me than thousands of gold and silver,’ Ps. 119:72; again (vv. 98-100): ‘Thou through Thy commandments hast made me wiser than mine enemies; for they are ever with me. I have more understanding than all my teachers; for Thy testimonies are my meditation. I understand more than the ancients, because I keep Thy precepts.’ And you will experience how flat and stale the books of the Fathers will taste to you; and not only will you despise the books of the opponents, but your own writings and teachings will please you the longer, the less. When you have arrived at this point, then you can confidently hope that you have made a beginning of becoming a real theologian, who can teach not only the young and immature Christians, but also the more mature, even the perfect Christians; for Christ’s Church contains all sorts of Christians, young, old, weak, sick, sound, strong, alert, lazy, foolish, wise, etc. But if you feel and think that you know it all and are tickled with your own booklets, your teaching and writing, as if you had produced something very precious and had preached admirably, and it pleases you much to be praised before others, yes, even expect such praise, so that you do not become depressed and lose interest: if you have that sort of a pelt, my friend, then take hold of your ears; and if you grab right, you will find a fine pair of large, long, shaggy ass’s ears; then risk the full cost and decorate yourself with golden bells, so that, wherever you walk, people can hear you, point you out, and say: ‘Look, lookl There goes that wonderful creature that can write such fine books and deliver such eloquent sermons.’ Then you are happy, and superhappy in heaven; ay, where the fire of hell is prepared for the devil and his angels! To sum up, let us seek honor and be elated where it is in place. In this Book the glory belongs entirely to God, and it says: ‘Deus superbis resistit, humilibus autem dat gratiam. Cui est gloria in saecula saeculorum. Amen!’ “ We advise all theologians and those who would become such to read Luther’s theological methodology repeatedly, in order to follow it by God’s grace, at all times.

1 A phrase employed by Nitzsch-Stephan, Lehrbuch der ev. Dogmatik, 3d ed., 1912, p. 13.

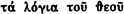

2 Luther’s term for Scripture, St. L. IX: 1071.

3 Sermons on Genesis, St. L. III:21.

4 Exeg. opp. Lat. Ed. Erl. IV, 328. St. L. I:1289 f.

5 Opp. v. a. VII, 166. St. L. XVIII: 1730.

6 Nitzsch-Stephan, Dogmatik, pp. 13, IX.

7 Exposition of the Last Words of David, 2 Sam. 23:3. St. L. III:1890. Erl. 37, 12.

8 Cicero derives religio from relegere or religere. De Nat. Deorum 2:28: “Men who make all those things that pertain to the worship of the gods the object of diligent study and close scrutiny are called religious because of this close study (relegendo), just as the elegant are called thus because of their choosing (eligendo), the diligent because of their giving close attention (diligendo), the intelligent because of their reflecting (intelligendo).” The Christian author Lactantius, on the other hand, derives religio from religare, in the sense of to bind, place under obligation to Cod. Inst. Div. 4:28: “By this bond of piety we are so obligated and bound [obstricti et religati] to God that therefrom religion itself received its name and not, as Cicero would have it, from relegere.” Augustine wavers between religere and religare. (Compare De Civ. Dei 10, 4 with De Vera Relig. c. 55.) Most of the older Lutheran theologians prefer the derivation from religare: Quenstedt, Syst., 1715, I. 28; Hollaz, Examen Proleg. II, qu. 2. Calov has a detailed account of the various derivations, Isag. I, 275 sqq. (See Baier-Walther, I, 14.) Modern theologians accept one or the other of the explanations mentioned or give other explanations; consult the larger encyclopedias. Voigt, Fundamentaldogmatik, pp. 1–30, discusses the question at great length.

9 H. Ebeling cites the axiom: “The etymology of a word usually sheds some light on its meaning but rarely covers the meaning it has acquired in common usage.” He adds: “Only in rare cases can the original meaning of a word be absolutely determined, and the historical development of the meaning and of the usage is something different from the etymology and the original meaning.” (Woerterbuch zum N. T. III, Introd.) Luther says on this point: ‘It is one thing to speak grammatically, another, to talk Latin. Therefore one must consider not so much the grammatical and regular language as the common usage…. In Latin many words have through usage acquired a meaning foreign to the grammatical laws.” (Opp. Exeg. Lat. VIII, 69.)

10 This definition of the pagan religion has always been quite generally accepted. Karl Stange, for instance, says: “The characteristic feature of the heathen religion is that it sees no other way to reconcile God and man than through human efforts and undertakings.” “The heathen religion instructs the sinner to remove the consciousness of sin by striving to make amends for his sin.” (Moderne Probleme, 1910, p. 183 f.) Luthardt: “It is the characteristic of heathenism to base the relation of God and man altogether on a quid pro quo arrangement, that is, to achieve salvation through works” (Glaubenslehre, 1898, p. 467). Thus also Ihmels (see Aus der Kirche, p. 52). And the Lutheran Confessions declare: “Works become conspicuous before men. Human reason naturally admires these, and because it sees only works, and does not understand or consider faith, it dreams accordingly that these works merit remission of sins and justify. This opinion of the Law inheres by nature in men’s minds; neither can it be expelled, unless we are divinely taught. Haec opinio legis inhaeret naturaliter in animis hominum.” (_Apology, _Trigl., 197, 144.)

11  — you become severed from Chirst, have no communion with Him. Cp. Cremer sub

— you become severed from Chirst, have no communion with Him. Cp. Cremer sub  . Luther: “Ihr habt Christum verloren, die ihr durch das Gesetz gerecht werden wollt.” You who imagine that you are justified through the Law. (R. V.: “would be justified.”)

. Luther: “Ihr habt Christum verloren, die ihr durch das Gesetz gerecht werden wollt.” You who imagine that you are justified through the Law. (R. V.: “would be justified.”)

12 The pagan, the Jewish, the Mohammedan, the Christian religion. Some Lutheran Catechisms, too, make this fourfold division.

13 This universality and exclusiveness of the Christian religion has already been prophesied in the Old Testament. Ps. 2:8: “I shall give Thee the heathen for Thine inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the earth for Thy possession.” Gen. 49:10; Ps. 72:8; etc.; Is. 49:6. Christ the “Light to the Gentiles and “My Salvation unto the end of the earth.”

14 Compare Luther’s comments on Is. 9.2 f., where he convincingly sets forth that all intellectual and moral endeavors of the heathen and unbelieving Jews leave men in darkness and despair. VI:106 ff. — The Lange-Schaff Commentary on Acts 26:18 says: “The purpose of Paul’s mission is stated in such a manner that it can be understood as referring only to Gentiles.” But Meyer’s Commentary is right when it points out that Paul himself declares that he was sent to the Jews and the Gentiles, v. 20, so that the phrase in v. 17: “Unto whom I now send thee” refers to “the people” (the Jews) and “the Gentiles.” — Meyer, however, is in error when he states that on the basis of the “turning from the power of Satan unto God” applies primarily to the Gentiles, since Paul in Eph. 2:3-4 expressly applies to the Jews what he says of the Gentiles in vv. 1 and 2.

15 Huttens Redivivus, 10th ed., p. 11.

16 Christian Dogmatics, Edinburgh 1898, p. 10.

17 Grundrisz, 3d ed., p. 10.

18 Eν. Dogmatik, 1912, p. 112.

19 Moritz von Engelhardt also states emphatically that there are only two religions in the world, two essentially different religions. (R. E., 2d ed., XVII, p. 773.)

20 Thus, e. g., Kirn, Grundrisz, 3d ed., p. 9.

21 Harless is right in putting into the domain of “dreams” the notion of Zwingli, Bucer, and others that an exception must be made in the case of certain individuals among the heathen. Luther against Zwingli’s beatification of the pagan heroes Hercules, Theseus, Socrates, etc. St. L. XX:1767. Certain heathen themselves have confessed that their situation is hopeless. See Luthardt, Apologetische Vortraege, I, 2, note 11.

22 F. Pieper, Das Wesen des Christentums, p. 5. [Max Mueller: wrong name.]

23 M. Heinze in R. E., 3d ed., XVI, 613 f.

24 Mansi, XX, 742.

25 Compare Luthardt, Dogmatik, 10th ed., p. 5 ff., in the chapter “Die Berechtigung der Theologie.” Harless had already expressed the same idea, Theol. Encyclopaedie, 1837, p. 27.

26 R. Seeberg, too, points out that Anselm and Abelard operate on the same rationalistic basis. Both give ratio a place beside faith. Dogmengeschichte II, 41 f.

27  here means God’s legislative and judicial righteousness. Cf. on the passage Stoeckhardt, Meyer, Philippi.

here means God’s legislative and judicial righteousness. Cf. on the passage Stoeckhardt, Meyer, Philippi.

28 Stoeckhardt on our passage: “Hofmann takes death to mean the death penalty inflicted by the government. Such an interpretation is altogether foreign to the text.” Philippi refers to the heathen teaching on Hades and its punishments and concludes: “Accordingly  in our passage should be interpreted as meaning the mors aeterna.”

in our passage should be interpreted as meaning the mors aeterna.”

29 Cf. Luther, St. L. I:230 ff., III:650 ff.

30 Luther discusses this matter at greater length in St. L. VII: 1704–1712.

31 John 8:31 f.: “If ye continue in My Word, then are ye My disciples indeed, and ye shall know the truth.” — John 17:20: “Which shall believe on Me through their Word.” All who come to faith in Christ are brought to faith, now and to the Last Day, through the Word of the Apostles. See also Eph. 2:20: “Ye are built upon the foundation of the Apostles and Prophets.”

32 See on this Nitzsch-Stephan, Eν. Dogmatik, p. 270; Hase, Hutterus Redivivus, 10th ed., p. 12, note 1.

33 The point under discussion has been treated in recent textbooks on dogmatics and monographs under titles such as: “Romanismus und Protestantismus,” “Der Lutherische und der Reformierte Protestantismus,” “Fortbildung des Luthertums,” “Moderne Theologie des Alten Glaubens,” “Irenic Theology,” etc.

34 Tridentinum, Sess. VI, Can. 11, 12, 20: “If any one saith, that men are justified, either by the sole imputation of the justice of Christ, or by the sole remission of sins, to the exclusion of the grace and the charity which is poured forth in their hearts by the Holy Ghost (Rom. 5:5) and is inherent in them; or even that grace, whereby we are justified, is only the favor of God; let him be anathema. — If any one saith, that justifying faith is nothing else but confidence in the divine mercy which remits sins for Christ’s sake; or that this confidence alone is that whereby we are justified; let him be anathema. — If any one saith, that the man who is justified and how perfect soever, is not bound to observe the commandments of God and of the Church, but only to believe; as if indeed the Gospel were a bare and absolute promise of eternal life, without the condition of observing the commandments; let him be anathema.” For a further discussion, see Vol. II, “The Papacy and the Doctrine of Justification.”

35 Apology: “Therefore, even though Popes, or some theologians, and monks in the Church have taught us to seek remission of sins, grace, and righteousness through our own works, and to invent new forms of worship, which have obscured the office of Christ, and have made out of Christ not a Propitiator and Justifier, but only a Legislator, nevertheless the knowledge of Christ has always remained with some godly persons” (Trigl. 225, 271).

36 Recent theologians: Gaussen, Kuyper, Bochl, Shedd, Hodge.

37 Statements characterizing the Lutheran and the Reformed Church in Luthardt, Dogmatik, 11th ed., p. 26 f.

38 See the chapters: “The Means of Grace in General” and “All Means of Grace Have the Same Purpose and the Same Effect,” in Vol. III.

39 Thus Zwingli, Fidei Ratio. Niemeyer, p. 24: “The Spirit needs no guide or vehicle, for He is Himself the power and the bearer by whom everything is borne, who needs not to be borne.” So also Calvin, Inst. IV, ch. 14, 17. “We get rid of that fiction by which the cause of justification and the power of the Holy Spirit are included in the elements as vessels and vehicles.” Geneva Catechism (Niemeyer, p. 161): “It does not inhere in the visible signs, so that we should have to seek salvation there.” Charles Hodge (Syst. Theol. II, 684): “Efficacious grace acts immediately.” Boehl, too, teaches that the Word is efficacious only in those who have already been regenerated, through the immediate operation of the Spirit. (Dogmatik, p. 447 f.)

40 Zwingli’s answer to Luther’s “That these words, etc.,” reprinted in the St. L. ed. of Luther’s Works, XX: 1131 f.: “I [Zwingli] am going to show you [Luther] that you have never grasped the vast and marvelous glory of the Gospel: and if you have once known it, you have forgotten it.”

41 Calvin, Inst. IV, ch. 17, 19: “The presence of Christ in the Supper must be such as neither divests Him of His just dimensions nor dissevers Him by differences of place, nor makes Him occupy a variety of places at the same time.” 29: “The essential properties of the body are to be confined by space, to have dimension and form.” Calvin adds: “Have done, then, with that foolish fiction which affixes the minds of men, as well as Christ, to bread.” In the same paragraph Calvin asserts that John 20:19 cannot mean that Christ with His body “penetrated through solid matter” — an opening had to be provided — and that Luke 24:31 does not say that Christ became invisible; it simply says that “their eyes were holden.”

42 So also Calvin, Inst., III, ch. 24, 17, 15: “However universal the promises of salvation may be, there is no discrepancy between them and the predestination of the reprobate, provided we attend to their effect. — Experience teaches that He does not will the repentance of those whom He externally calls, in such a manner as to affect all their hearts.”

43 Calvin argues against the universality of God’s gracious will on the basis of God’s omnipotence: ‘If they obstinately insist on its being said that God is merciful to all, I will oppose to them what is elsewhere asserted, that our God is in the heavens, where He hath done whatsoever He hath pleased, Ps. 115:3” (Inst. III, ch. 24, par. 16). Hodge: “It cannot be supposed that God intends what is never accomplished — that He adopts means for an end which is never to be attained. This cannot be affirmed of any rational being who has the wisdom and power to secure the execution of his purposes. Much less can it be said of Him whose power and wisdom are infinite. (Loc. cit.) — It should be noted here that in quoting Ps. 115:3 Calvin takes the liberty to change the wording. The words: “But our God is in the heavens; He hath done whatsoever He hath pleased” set forth the omnipotence of God in contrast to the impotence of the idols of the pagans, as set forth in the next verse: “Their idols are silver and gold, the work of men’s hands.” Calvin’s insertion of the ubi: “Our God is in the heavens, ubi faciat quaecumque velit” (where He does whatsoever He pleases) changes the meaning completely. It makes the text say that God wills and does otherwise in heaven than on earth.

44 Schneckenburger shows in detail how in his pastoral practice the Calvinist finds himself operating with the Lutheran gratia universalis. (Vergleichende Darstellung d. luth. u. ref. Lehrbegriffs I, 260 ff. See Pieper, III, 201.)

45 The Apol. Conf. Remonstr. declares (p. 162) that the divine grace working towards conversion “cannot accomplish anything without the cooperation of man’s free will and therefore its success depends on the free will.”

46 This is presented in detail under “Conversion” in Vol. II and “Final Perseverance” in Vol. III.

47 “As long as man has any persuasion that he can do even the least thing toward his own salvation, he retains a confidence in himself, he does not humble himself before God, but proposes to himself some place, some time, or some work, whereby he may at length attain unto salvation” (Luther, St. L. XVIII:1715).

48 Apology: “As often as we speak of faith, we wish an object to be understood, namely, the promised mercy” (Trigl. 136, 55).

49 Theologie der Konkordienformel I, 135. In De Servo Arbitrio Luther mentions certain advocates of free will who, when dealing with God, forget their synergistic theories. He says (St. L. XVIII:1730): “When they are engaged in words and disputations, they are one thing, but another when they come to experience and practice…. When they approach God, either to pray or to do, they approach Him utterly forgetful of their own ‘free will’ and, despairing of themselves, cry unto Him for pure grace only.” See also Mead, Irenic Theology, p. 163.

50 Thieme in R. E., 3d ed., XXI, 120.

51 St. L. XX: 1094 ff. Erlangen 30, 363 ff. F. C., Trigl., 981 f.

52 The Formula of Concord, Trigl., 1071, 28-29; 837, 17-19 confesses the gratia universalis, and 788, 9-11; 1081, 57-64, the sola gratia, and forgoes all attempts to ease this crux theologorum. Likewise Luther, De Servo Arbitrio, St. L. XVIII: 1965 f.

53 Seeberg, Dogmengeschichte, I, 138. F. H. Foster in the Concise Dictionary by Jackson, Chambers and Foster: “The theoretical difference grew out of a personal one.”

54 See, for example, the German Agende of the Missouri Synod, p. 44 f.; 58 f. See also Walther, Pastorale, p. 389 f., Note 1. [Fritz, Pastoral Theology, 1945, p. 323 f.]

55 Nitzsch-Stephan presents the matter thus: “The primary defect of Kant’s [ethical] interpretation of Christianity inheres also in those interpretations which hold that the Christian religion is the perfect religion for no other reason than that it is the religion of love towards God and men. Now, it is true that Christianity stresses the duty of love towards God and all men as no other religion does. But mere obligations do not constitute a religion and the Christian’s love is not merely to be patterned after God’s love, but according to our Christian faith the love of God is the prerequisite and enabling cause of our love. We love because we know and realize that God, redeeming us and forgiving us our sins, first loved us.” (Op. cit., p. 147.) Ihmels, too, states that “the ethical quality of any activity or movement is not determined by the individual external actions but solely by the motives from which the ethical behavior flows” (Zentralfragen, p. 51).

56 Col. 2:10: “Ye are complete in Him.” Not only the “more advanced” Christians, but all who have received Christ Jesus the Lord by faith, vv. 5, 7, are perfect in Christ. The Apostle is here warning the Christians against the philosophy which belittles our perfection in Christ and sets itself up as the way to greater perfection, v. 8; they must learn that the philosophy which claims authority in the domain of religion is “vain deceit,”  , being the product of man (“after the tradition of men”), the beggarly wisdom of the world (“after the rudiments of the world”), that is, Law. (See Cremer, Woerterbuch, sub

, being the product of man (“after the tradition of men”), the beggarly wisdom of the world (“after the rudiments of the world”), that is, Law. (See Cremer, Woerterbuch, sub  .) — The Christians, on the contrary, have their “doctrinal norm” in Christ (“after Christ”), and through that they have obtained the highest perfection. Let them realize the glory of Christ’s person and the unsurpassable excellence of the benefits they have in Christ. Christ is not a mere man, but one in whom all the fullness of the Godhead dwells bodily and who is exalted above all principalities and powers in heaven; it is therefore impossible that these angelic powers should be the source of a higher perfection, as the false teachers asserted (v. 18). And no greater benefit can come to the Christians than those which they have in Christ; they have been raised from death in sin to spiritual life through “the circumcision of Christ,” namely, Baptism, through the forgiveness of their sins. And this remission Christ gained through His death on the Cross (“the objective propitiatory sacrifice of Christ’s death,” v. 14, Meyer), by which He has blotted out the handwriting of ordinances against us, the penalty exacted by the Law.

.) — The Christians, on the contrary, have their “doctrinal norm” in Christ (“after Christ”), and through that they have obtained the highest perfection. Let them realize the glory of Christ’s person and the unsurpassable excellence of the benefits they have in Christ. Christ is not a mere man, but one in whom all the fullness of the Godhead dwells bodily and who is exalted above all principalities and powers in heaven; it is therefore impossible that these angelic powers should be the source of a higher perfection, as the false teachers asserted (v. 18). And no greater benefit can come to the Christians than those which they have in Christ; they have been raised from death in sin to spiritual life through “the circumcision of Christ,” namely, Baptism, through the forgiveness of their sins. And this remission Christ gained through His death on the Cross (“the objective propitiatory sacrifice of Christ’s death,” v. 14, Meyer), by which He has blotted out the handwriting of ordinances against us, the penalty exacted by the Law.

The “perfect,”  , of 1 Cor. 2:6, too (“howbeit we speak wisdom among them that are perfect”), are not the “mature” Christians, those who have penetrated “into the higher sphere of thorough and comprehensive insight,” particularly of an insight into “the future conditions of the Messianic kingdom” (Meyer, etc.), but according to the context all those who through the operation of the Holy Ghost believe the Gospel, which is hidden to this world, even to the princes of this world. The “perfect” are all Christians (Luther, Olshausen, etc.). Wolf’s Curae reviews the various interpretations of our passage and finds with Luther and most other interpreters that the “perfect” are the believers, those who are described in ch. 1:24 as “the called,” those who obeyed the call. In the entire context nothing is said of “future conditions of the Messianic kingdom” (an interpretation that is colored by chiliastic notions), nor does the context deal specifically with the future bliss of the Christians (some have thus applied verse 9), but only with what they now have by faith in the Gospel of Christ Crucified.

, of 1 Cor. 2:6, too (“howbeit we speak wisdom among them that are perfect”), are not the “mature” Christians, those who have penetrated “into the higher sphere of thorough and comprehensive insight,” particularly of an insight into “the future conditions of the Messianic kingdom” (Meyer, etc.), but according to the context all those who through the operation of the Holy Ghost believe the Gospel, which is hidden to this world, even to the princes of this world. The “perfect” are all Christians (Luther, Olshausen, etc.). Wolf’s Curae reviews the various interpretations of our passage and finds with Luther and most other interpreters that the “perfect” are the believers, those who are described in ch. 1:24 as “the called,” those who obeyed the call. In the entire context nothing is said of “future conditions of the Messianic kingdom” (an interpretation that is colored by chiliastic notions), nor does the context deal specifically with the future bliss of the Christians (some have thus applied verse 9), but only with what they now have by faith in the Gospel of Christ Crucified.

57 Tridentinum, Sess. VI, Can. 11, 12, 20.

58 Thus, e. g., Kirn, Grundriss, 3d ed., p. 118. This substitutes the “Guarantee Theory” for the satisfactio Christi vicaria.

59 See “Some Modern Theories of the Atonement Examined” in Vol. II.

60 Wesen des Christentums, 3d ed., p. 35.

61 The rhetorical question: “Are they all teachers?” (1 Cor. 12:29) means that not all Christians are teachers. According to 1 Tim. 3:2 one who would be a bishop must be  “apt to teach,” have a special degree of the ability to teach, for, according to verse 5, he is to take care not only of himself and his own house, but also of the Church of God. Paul stresses this once more in 2 Tim. 2:2: “The things that thou hast heard of me among many witnesses, the same commit thou to faithful men who shall be able to teach others also.” Therefore men must not be elected to the teaching office by lot or in any other haphazard way; only such may be chosen as possess the qualifications set down in 1 Tim. 3:1 ff.; Titus 1:5-11, one of which is a special aptitude to teach.

“apt to teach,” have a special degree of the ability to teach, for, according to verse 5, he is to take care not only of himself and his own house, but also of the Church of God. Paul stresses this once more in 2 Tim. 2:2: “The things that thou hast heard of me among many witnesses, the same commit thou to faithful men who shall be able to teach others also.” Therefore men must not be elected to the teaching office by lot or in any other haphazard way; only such may be chosen as possess the qualifications set down in 1 Tim. 3:1 ff.; Titus 1:5-11, one of which is a special aptitude to teach.

62 See, for instance, Richard Gruetzmacher, Studien zur dogm. Theol., 3, p. 120 ff.

63 According to John 8:31-32 the knowledge of the truth is mediated by the Word of Christ, which we have in the Word of His Apostles (John 17:20): “If ye continue in My Word … ye shall know the truth.” And only by believing Christ’s Word do men “continue in it.” When a teacher does not continue in Christ’s Word, the Apostle does not credit him with knowledge but with ignorance (1 Tim. 6:3-4).

64 Cf. Zezschwitz, R. E., 2d ed., VII, 585 ff. Luther in his “Short Preface” to the Large Catechism defines a catechism as “an instruction for children and the simple-minded,” as an “instruction for children, what every Christian must needs know, so that he who does not know this could not be numbered with the Christians, nor be admitted to any Sacrament” (Trigl. 575). Cf. F. Bente, in Concordia Triglotta, “Historical Introductions,” pp. 62–93, on catechisms in general and Luther’s Catechism in particular, also for a bibliography of recent literature.

65 Luthardt, Kompendium, p. 4. Walther, Lehre und Wehre, 14, 5. Augustine, De Civ. Dei, VIII, 1: “We understand the Greek theologia to mean the knowledge and doctrine of the deity” (ratio sive sermo).

66 Aristotle says that Thales and those who before him speculated on the origin of things “theologized,”  (Metaph. I, 3). According to Josephus, Pherekydes of Syros in the sixth century wrote a book with the title Theologia, in which he philosophized about the heavens and things divine (C. Apionem, I, 2). Cicero writes: “In the beginning there were three Joves — so say those who are called theologians” (De Nat. Deorum III, 21). Augustine quotes Varro, a contemporary of Cicero, on three types of heathen theology: “The mythical genus, used mostly by the poets; the physical, used by the philosophers; and the civil, which the people and the priests should know and employ.” (De Civ. Dei, VI, 5.) — Study Augustine’s criticism of the heathen theology in this and the following chapters. See further Buddeus, Inst., 1741, p. 48 sqq. August Hahn, Lehrbuch d. Chr. Gl., 2d ed., I, 104 f.; Walther, Lehre und Wehre, 1868, p. 5 f.

(Metaph. I, 3). According to Josephus, Pherekydes of Syros in the sixth century wrote a book with the title Theologia, in which he philosophized about the heavens and things divine (C. Apionem, I, 2). Cicero writes: “In the beginning there were three Joves — so say those who are called theologians” (De Nat. Deorum III, 21). Augustine quotes Varro, a contemporary of Cicero, on three types of heathen theology: “The mythical genus, used mostly by the poets; the physical, used by the philosophers; and the civil, which the people and the priests should know and employ.” (De Civ. Dei, VI, 5.) — Study Augustine’s criticism of the heathen theology in this and the following chapters. See further Buddeus, Inst., 1741, p. 48 sqq. August Hahn, Lehrbuch d. Chr. Gl., 2d ed., I, 104 f.; Walther, Lehre und Wehre, 1868, p. 5 f.

67 Quenstedt I, 13: “Theologia acroamatica teaches and establishes the mysteries of the faith and refutes the errors contrary to the sound doctrine more accurately and copiously, and is the province of the bishops and preachers in the Church.” [According to Koenig, theology is divided into: ‘catechetical, or simple, such as is required of all Christians, and acroamatic, or more accurate, which is the province of the learned, the ministers of the Word.’ “]

68 Quenstedt, I, 13: “Theologia acroamatica is the province of those who in the seminaries instruct, not Christians but the future teachers of the Christians; and these are called theologians  .” — Luther has some interesting remarks on the theological doctorate. He calls the pomp and ceremony connected with the conferring of this degree “Larven,” mummeries. But he does not condemn the thing outright. It is all right if the recipients of the high degree recognize that while the thing in itself means nothing, the honor conferred on them is the honor of “the service in the Word.” (St. L. XXI a:564. II:260.)

.” — Luther has some interesting remarks on the theological doctorate. He calls the pomp and ceremony connected with the conferring of this degree “Larven,” mummeries. But he does not condemn the thing outright. It is all right if the recipients of the high degree recognize that while the thing in itself means nothing, the honor conferred on them is the honor of “the service in the Word.” (St. L. XXI a:564. II:260.)

69 Luther also calls the centurion at Capernaum a “theologus” because he “argued in such a fine Christian way that one who has been a doctor for four years could not have done better” (St. L. XII: 1185). And on Rom. 12:7 Luther comments: “Hence you will perceive whom Paul makes doctors of Holy Scripture, namely, all who have the faith, and no one else. They should judge all doctrine, and their decision must stand, even though it be against the Pope, the councils and all the world.” (St. L. XII:335.) Gerhard, too, says that the term theology is used “for the Christian faith and religion as it is found in all believers, the learned as well as the unlearned, and in this sense all who know and accept the articles of faith” (locus “De Natura Theologiae,” §4), “who teach and profess these articles” (locus “De Ministerio Ecclesiastico,” §64), are called theologians. According to 1 Pet. 3:15, Col. 3:16, etc., it is the business of the Christians in general to teach and profess the Christian faith and religion. — There are those among the so-called laymen whose knowledge of the Christian doctrine and whose interest in the affairs of the Church exceeds the average. We like to call them “lay theologians.” The Apostolic Church had such lay theologians. The list of greetings in Romans 16 seems to indicate that. In the vast majority of cases the lay theologians have proved a blessing to the Church. Lehre und Wehre, 1860, p. 352, shows that the fear of having “laymen at the synodical conventions” is unwarranted.

70 Thus Gregory Nazianzen (d. ca. 390) was called  because in speech and writing he had so ably defended the doctrine of the deity of Christ. And we know that the Church Fathers called the evangelist John 6

because in speech and writing he had so ably defended the doctrine of the deity of Christ. And we know that the Church Fathers called the evangelist John 6  because his Gospel lays particular stress on the eternal, essential deity of Christ. Thus Athanasius (4th century): “As also the theologian says: ‘In the beginning was the Word.’ ” The Church Fathers distinguished between theology as the doctrine of the deity of Christ and

because his Gospel lays particular stress on the eternal, essential deity of Christ. Thus Athanasius (4th century): “As also the theologian says: ‘In the beginning was the Word.’ ” The Church Fathers distinguished between theology as the doctrine of the deity of Christ and  (dispensano) as the doctrine concerning the incarnate Christ. Thus Gregory Nazianzen: “The doctrine of the theology or of the nature is one thing, the doctrine of the economy is another.” — By reason of this specific sense of

(dispensano) as the doctrine concerning the incarnate Christ. Thus Gregory Nazianzen: “The doctrine of the theology or of the nature is one thing, the doctrine of the economy is another.” — By reason of this specific sense of  the verb

the verb  , to theologize, came to be used in the sense of “confessing as God.” Thus Athanasius: “How can you theologize the Spirit (confess the Spirit as God) if you are not ready to say that He has the same essence and glory, will and power, as the Father and the Son?” (De S. Trin., dial. 3. Opp. ed. Bonutius II, 190 sq. Quoted by Walther in Lehre und Wehre, 1868, p. 7.) — Basilius uses the word theology to designate the doctrine of the mystery of the Trinity: “Had we not better remain silent lest the dignity of theology be endangered because of the poverty and weakness of the language?” (Sermo de fide et trinitate. Opp. I, 371. Lehre und Wehre, 1868, p. 8.)

, to theologize, came to be used in the sense of “confessing as God.” Thus Athanasius: “How can you theologize the Spirit (confess the Spirit as God) if you are not ready to say that He has the same essence and glory, will and power, as the Father and the Son?” (De S. Trin., dial. 3. Opp. ed. Bonutius II, 190 sq. Quoted by Walther in Lehre und Wehre, 1868, p. 7.) — Basilius uses the word theology to designate the doctrine of the mystery of the Trinity: “Had we not better remain silent lest the dignity of theology be endangered because of the poverty and weakness of the language?” (Sermo de fide et trinitate. Opp. I, 371. Lehre und Wehre, 1868, p. 8.)

71 Quenstedt: “Theology taken concretely as a habitus is the God-given practical aptitude of the mind which the Holy Ghost bestows upon a man through the Word, for the purpose of leading sinful man to faith in Christ, and to eternal salvation” (Systema I, 16). Similarly Gerhard (locus “De Natura Theologiae,” ¶31).

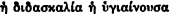

72 Quenstedt: “Theology taken abstractly as a system is the body of doctrine taken from the Word of God, by which men are correctly instructed in faith and life unto salvation; in other words, it is the doctrine drawn from the divine revelation that shows how men are to be trained for the service of God through Christ unto eternal life” (I, 16).

73 “Can you imagine St. Paul writing a normative dogmatics after the manner of Hutter’s Compendium Locorum Theologicorum?” Thus the advocates of “academic freedom.” It is a cheap quip and falls flat in the light of 2 Tim. 1:13. The passage states very clearly, first, that Timothy heard  (sound words) from the Apostle, words that did not express unsound human opinions, but the pure divine truth; and, secondly, that Paul set these “sound words” before Timothy not as matter of passing entertainment or mere amusement, but as the

(sound words) from the Apostle, words that did not express unsound human opinions, but the pure divine truth; and, secondly, that Paul set these “sound words” before Timothy not as matter of passing entertainment or mere amusement, but as the  , copy, model, pattern, norma sanorum verborum, by “which Timothy should be guided in his teaching. Note also the

, copy, model, pattern, norma sanorum verborum, by “which Timothy should be guided in his teaching. Note also the  , “hold,” “hold fast”; Timothy is not at liberty to depart from the norm set up by Paul. According to this text, then, Paul did write what we would call a “Normaldogmatik.” Plitt on our passage: “What I have given you use as a pattern, namely, the sound words, ‘the sound doctrine’ (Titus 1:9).” Matthies: “

, “hold,” “hold fast”; Timothy is not at liberty to depart from the norm set up by Paul. According to this text, then, Paul did write what we would call a “Normaldogmatik.” Plitt on our passage: “What I have given you use as a pattern, namely, the sound words, ‘the sound doctrine’ (Titus 1:9).” Matthies: “ , pattern, as in 1 Tim. 1:16, distinct type, original and model.” Huther (Meyer’s Commentary) remarks: “Luther translates

, pattern, as in 1 Tim. 1:16, distinct type, original and model.” Huther (Meyer’s Commentary) remarks: “Luther translates  by ‘pattern’ (so, too, De Wette, Wiesinger, and others), but this definition is not in the word itself.” But the words of the text plainly show that Paul is referring to a “pattern.” The

by ‘pattern’ (so, too, De Wette, Wiesinger, and others), but this definition is not in the word itself.” But the words of the text plainly show that Paul is referring to a “pattern.” The  by which men are to be guided becomes eo ipso a pattern.

by which men are to be guided becomes eo ipso a pattern.

74 Musaeus: “The doctrine regarding God and divine matters issues from the theological aptitude and is its result” (Introd. in Theol. 1679, p. 3). Luthardt holds that the old Lutheran theologians, who defined theology primo loco as a personal aptitude, “a personal qualification,” meant well, but finds that “this definition is scientifically incorrect” (Komp., 10th ed., p. 4). We fail to see why this definition should be out of line with scientific thinking. Why, Luthardt himself thinks along the same lines! When he with Kahnis defines theology as “the scientific self-consciousness of the Church,” he, too, conceives of theology as a “personal qualification,” since every kind of “self-consciousness,” including the “scientific” kind, presupposes persons, in whom it inheres as a personal attribute. An impersonal self-consciousness is a contradiction in itself. Luthardt will not deny that he, too, has in mind persons within the Church, viz., the theologians who, in distinction from the ordinary Christians, possess a scientific self-consciousness. It is a queer thing by the way, that Luthardt, while thinking of theologians, should define theology as “the scientific self-consciousness of the Church.” The theologians, whether they are equipped with scientific self-consciousnes or not, are not the Church.

75 Cf. Walch, Bibliotheca Theol., II, 667 sqq.; Baumgarten, Theol. Streitigkeiten, III, 425 f.; there is a wealth of material on the controversy concerning this point in Hollaz, Examen Prol., I, qus. 18–21.

76 It is not correct to say that Spener was the first to emphasize this truth. In his tract “Die Allgemeine Gottesgelehrtheit” Spener himself says that others have done that before him. (See Baier, loc. cit.)

77 Quenstedt: “In the field of polemical theology we must take special care not to engage in controversies over useless questions and not to let controversies breed controversies; polemics must not become a quarrelsome and contentious theology, by which the truth is lost through too much disputing” (Systema I, 14).

78 1 Pet. 4:11: “If any man speak, let him speak as the oracles of God.” No doctrine may be preached in the Church but “the doctrine of God our Savior” (Titus 2:10).

79 What the Apostles taught orally, that ( ) they also set down in writing (1 John 1:3-4).

) they also set down in writing (1 John 1:3-4).

80 Aug. Pfeiffer: “Theologia positiva, theology in the form of doctrine, is, correctly speaking, nothing else than Holy Scripture itself arranged according to doctrines, its statements set down in the various loci according to a proper method and in fitting order; it follows that in this body of doctrine there is no place for even one article, and be it the least one, which is not based on Scripture” (Thesaurus hermeneut., p. 5, quoted in Baier, I, 43, 76).

81 Comment, ad Gal, see Erl. I, 91: “Neque alia doctrina in ecclesia tradì et audiri debet quam purum Verbum Dei, hoc est, Sancta Scriptura, vel doctores et auditores cum sua doctrina anathema sunto.” St. L. IX:87.

82 This will be presented in detail in the section “The Vicarious Satisfaction’ in Vol. II.

83 Parallel passages: Jer. 14:14; 27:14-16; Lam. 2:14; Ezek. 13:2 ff.

84 “Let him speak as the oracles of God.” Luther: “He should be certain that what he is speaking is God’s Word and not his own word” (XII:443).

85 Kahnis, for instance, is very outspoken on this point. In his Zeugnis von den Grundwahrheiten des Protestantismus gegen D. Hengstenberg, Leipzig, 1862, p. 133, he says: “I have not written my dogmatics for the general public, not for the educated laymen, but only for scientific theologians. However, after Dr. Hengstenberg and Dr. Muenkel have, in a most unwarranted manner, brought the matter to the attention of wider circles, I have been forced to address, at least in this essay, a wider circle than the readers of my dogmatics.” Again on page 118 f.: “I cannot believe that Pastor Muenkel, who signs himself Th. D., knows so little of theology that he does not know that there are difficulties in theology which have to be discussed. These investigations and discussions are of course not meant for the common people. But who is spreading them there? Why, periodicals like Pastor Muenkel’s paper. Do not charge me with confusing the people; the blame rests with this man, who, while he is neither a man of science nor a man of the people, goes about like a telltale and scares people by telling them things which they need not know. If Pastor Muenkel cannot stand the mountain heights with their avalanches and landslides, he had better stay on the Lueneburger Heide and tend sheep, raise bees, and grow asparagus.” — It is only natural that Kahnis, who denies that the Holy Scripture is “the inspired textbook of the pure doctrine” (p. 127), would insist that it requires the scientific apparatus of the theologians to establish what is Christian doctrine.

86 Bretschneider, Systematische Entwicklung aller in der Dogmatik vorkommenden Begriffe, 3d ed., p. 68.

87 Zeitschrift f. luth. Theol. u. Kirche, 1848, I, 7; quoted in Baier-Walther, I. 5.

88 Systema, Proleg. de Theologia, p. 2, in Quenstedt, Syst., I, 5 sq., under Thesis IV.

89 He writes in the locus “De Natura Theologiae,” §15 sqq.: “The archetypal, or prototypal, theology is in God the Creator, inasmuch as God knows Himself in Himself and knows the universe through Himself by one immutable act of knowing. Ectypal theology is the outgrowth of archetypal theology (a copy, so to say, of it), communicated to man through God’s grace.” The means by which this knowledge, original only in God, is communicated, is the external Word, “by which God here in time speaks to men.” It follows that Christian theology takes its teaching exclusively from Scripture: “The supernatural, adequate, and proper principle of theology is the divine revelation; and because we today have this divine revelation nowhere else than in the sacred writings, that is, in the prophetic books of the Old Testament and the apostolic books of the New Testament, we say that the written Word of God, that is, Holy Scripture, is the only and the proper principle of theology.” Cp. also Quenstedt, Syst., I, 5 sqq.

90 Systerna, p. 2: “So far as it [the theology of the “pilgrims”] reproduces and expresses the archetype revealed to us in the Word, it is true theology. Whatever deviates from that archetype is false theology and heretical mataeology.”

91 Nitzsch-Stephan, p. 258: “In our day the orthodox doctrine of inspiration has hardly any standing in dogmatics.” Horst Stephan: “Today the doctrine of inspiration is discarded by scientific theology; it has retained its hold — a strong one at that — only in the theology of the laymen” (Glaubenslehre, 1921, p. 52).

92 Nitzsch-Stephan, p. 12 ff. 15: “No one bases his dogmatics on the norma normans” (the Bible), “as was the fashion among the old Protestants.”

93 Scripture demands 1 Cor. 1:10 that “ye all speak the same thing: … that ye be perfectly joined together in the same mind and the same judgment”; Eph. 4:5: one faith.” The “sound words,” 2 Tim. 1:13, the “sound doctrine,”  (Luther: “die heilsame Lehre”), Titus 1:9; 1 Tim. 6:3; 2 Tim. 1:13; 4:3; 1 Tim. 1:10, is the “pure doctrine” (reine Lehre), God’s own doctrine, unmixed with human thoughts; as the Apostle himself explains the term (1 Tim. 6:3).

(Luther: “die heilsame Lehre”), Titus 1:9; 1 Tim. 6:3; 2 Tim. 1:13; 4:3; 1 Tim. 1:10, is the “pure doctrine” (reine Lehre), God’s own doctrine, unmixed with human thoughts; as the Apostle himself explains the term (1 Tim. 6:3).

94 Glaubenslehre, Giessen 1921, p. 21.

95 They even quoted 2 Cor. 3:3: “Ye are … the epistle of Christ ministered by us, written not with ink, but with the spirit of the living God.” Francis Coster asserts in his Enchiridion Controversiarum Praecipuarum, c. 1, p. 43, that “Christ did not want to have His Church depend on something written on paper, nor would He entrust His mysteries to parchments.” (See Quenstedt, I, 90, 92.)

96 See the quotations in chapter 5: “The Cause of Divisions.”

97 Compare Zwingli’s admonition that “no one should permit the anxious searching of the words [the words of institution] to raise scruples in his mind; for we do not base our doctrine on them” (reprinted in Luther’s Works, St. L. XX:477).

98 Quoted in Ihmels, Zentralfragen, p. 60; Ihmels discusses this “psychological point of contact,” p. 78.

99 Schriftbeweis, 2d ed., I, 562.

100 For further discussion of this point see Vol. II, the last section of the chapter “The Personal Union and the Christological Theories of Modern Theology,” and chapter 8 of “Saving Faith.”

101 Nitzsch-Stephan, p. 7: “Julius Kaftan and Herrman are the most radical proponents of this view. But also Ihmels insists that ‘only those things need to be sharply defined of which faith is immediately certain’ (Zentralfragen, p. 101).”

102 Ihmels, Aus der Kirche etc., 1914, p. 18.

103 See his book “Der Glaubensakt des Christen, nach Begriff und Fundament untersucht,” 1891, p. 119. Also his Theologie des A. T., 1921, p. 313.

104 See Ed. Koenig, Der Glaubensakt, p. 63; Concise Dictionary of Rel. Knowledge, by Jackson, sub “Lessing.”

105 Bertheau in R. E. 2d ed., VIII, 611.

106 Before there was a written Word, the spoken Word of God served the same purpose. God has always accompanied the historical facts through which He effected our redemption with His historical Word, lest men indulge in their own thoughts about the appearance of the Son of God in the flesh.

107 Studien zur systematischen Theologie, Vol. III, p. 40. Gruetzmacher unfortunately does not always apply the truth he so well expresses.

108 Moderne Theologie des Alten Gkubens, 1906, p. 120 f.

109 Dogmatische Studien, Erlangen and Leipzig, 1892, pp. 104–135.

110 Glaubenslehre, 1921, p. 183.

111 Kirn, R. E., 3d ed., XX, 574; also in his Ev. Dogm., 3d ed., p. 118. Cp. the section “Some Modern Theories of the Atonement Examined” in Vol. II.

112 Throughout Scripture God’s Law is taught (Matt. 22:37-40), and throughout Scripture God’s Gospel is taught (Rom. 1:1-2; 3:21; Acts 10:43). The Apology states: “All Scripture ought to be distributed into these two principal topics, the Law and the promises. For in some places it presents the Law, and in others the promise concerning Christ.” (Trigl. 121, 5.)

113 Luther: “Die da glaubeten an den Herrn.”

114 See the section “Saving Faith Is Trust in the Grace That is Offered to Us in the Gospel” in Vol. II, p. 446 ff. — The old distinction between the fundamentum substantiale [Christ] and the fundamentum organicum [the Word of the Gospel] does not set up two separate and distinct foundations of faith, but simply emphasizes, as Hollaz points out (Examen, Proleg., C. 2, qu. 19), the all-important truth that faith can lay hold of Christ only by way of laying hold of the Word. The modern theologians who refuse to accept the Word of the Apostles and Prophets of Christ as God’s Word substitute for the fundamentum organicum “the Person of Christ,” “the living Christ,” etc., as the foundation of faith. But he who by-passes Christ’s words also misses the “living Christ.”

115 Lehre und Wehre, 67, p. 1 ff.

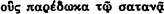

116 Huther on the words:  : “It is the same excommunication as in 1 Cor. 5:5.”

: “It is the same excommunication as in 1 Cor. 5:5.”

117 The Biblical doctrine of the resurrection of the dead is fully presented in the chapter on “The Resurrection of the Dead,” in Vol. III.

118 Nikolaus Hunnius’  Theologica de Fundamentali Dissensu (1626) and Joh. Huelsemann’s Calvinismus Irreconciliabilis (1646). Walch, Bibliotheca Theologica, II, 486 ff., discusses the complete bibliography, covering also the Reformed writings.

Theologica de Fundamentali Dissensu (1626) and Joh. Huelsemann’s Calvinismus Irreconciliabilis (1646). Walch, Bibliotheca Theologica, II, 486 ff., discusses the complete bibliography, covering also the Reformed writings.

119 This is fully discussed in the section “Baptism a True Means of Grace,” in Vol. III.

120 This is the case with the children of God in the Reformed bodies, who, misled by their teachers, fail to use Baptism and the Lord’s Supper as divinely appointed means of justification. Believing the Gospel, they have the full forgiveness of their sins, full salvation. Both Luther (St. L. XVII: 2212) and the Preface to the Book of Concord (Trigl. 19 f.) call attention to this.

121 “As long as he [man] is persuaded that he can do even the least thing towards his own salvation, he retains some confidence in himself, he does not humble himself before God, but proposes to himself some place, some time, or some works whereby he may at length attain unto salvation” (The Bondage of the Will, St. L. XVIII:1715).

122 Caloinismus Irreconciliabilis, p. 432, quoted in Baier-Walther, 1:62: “Not every teaching which in its nature adds or destroys some prerequisite necessary to faith or some consequence of it, also has this effect in the mind of every man.”

123 In the Prologue to his Retractationes Augustine says: “From ever so many of my disputations many things could be collected which, if not false, still certainly appear so or, in other cases, do not necessarily prove convincing. But what faithful servant of Christ does not tremble at this word of Christ: ‘Every idle word that men shall speak, they shall give account thereof in the Day of Judgment’? (Matt. 12:36.)” Augustine continues: “It behooves me therefore that I judge myself under the one Master whose judgment of my offenses I desire to escape.” (Ed. Basil. I, 1.)

124 Luther’s classical dictum on “the Christian error”: “You cannot say, I am going to err after the manner of a Christian; a Christian errs unwittingly” (St. L. XIX:1132).

125 The meaning of the hapax legomenon  is clear beyond any doubt. It designates the inner self-condemnation, suopte judicio condemnatus. God’s Word, with which he has been confronted, has condemned him, and he has felt this condemnation in his conscience. Huther on this passage: “He sins, being conscious of his guilt and condemnation.”

is clear beyond any doubt. It designates the inner self-condemnation, suopte judicio condemnatus. God’s Word, with which he has been confronted, has condemned him, and he has felt this condemnation in his conscience. Huther on this passage: “He sins, being conscious of his guilt and condemnation.”

126 1 Cor. 5:6: “A little leaven leaveneth the whole lump.” Hence 2 Cor. 7:1 admonishes us to “cleanse ourselves from all filthiness of the flesh and spirit.”

127 Meyer, too, like Luther and our old theologians, refers Gal. 5:9 to the domain of doctrine.

128 See the case of Adam Neuser, in Vol. II, in the section “The Doctrine of Christ” (p. 273 f.).

129 R. E., 2d ed., VI, 777 (Trigl., “Historical Introductions,” p. 98).

130 Cardinal Bellarmine taught a grave error when he said: “Catholics extend the object of justifying faith as far as the Word of God extends” (Lib. I, De Justif., c. 4. See Quenstedt, II, p. 362). That would make saving faith a work. Over against this error it needs to be stressed that the only object of the fides justificans is the promise of the Gospel, offering the remission of sins for Christ’s sake. See the section “The Sole Object of Saving Faith Is the Gospel” in Vol. II.

131 See the addition to the third edition of his Glaubenslehre I, 279; also Proceedings of the Synodical Conference, 1886, p. 35.

132 Compare F. Bente, American Lutheranism, II, p. 9. The same unionism and indifferentism infected the former General Synod, pp. 19, 48, 170; the General Council, pp. 195, 224; and the United Synod of the South, p. 232 ff.

133 More on this in the locus on “Holy Scripture,” in the chapter “The Authority of Scripture and the Confessions.”

134 The attempt to solve this problem has led to Dualism in its various forms, and to the denial of sin. Nitzsch-Stephan, Ev. Dogmatik, 3d ed., p. 438. More particulars in section “The Doctrine of God.”

135 This question was discussed at great length during the Pelagian controversies, but also in later periods. See Chemnitz, Loci, I, “De Peccato Originis,” ed. 1599, I, 567 sqq., for the historical material. On Luther’s position Chemnitz says: “Luther declared that publicly he would assert nothing in answer to this question, but that he, for himself, favored traducianism; furthermore, that the Papists must be censured for their audacity and presumptuousness in creating an article of faith in an obscure matter, without one clear testimony of Scripture, in order to subvert the Scripture doctrine of original sin.” Chemnitz adds: “… let us learn from this example to cut short, piously, firmly, and in well-founded simplicity, these subtle disputations which endanger faith. As to the causa efficiens [of original sin], it is sufficient to know that the fall of our first parents justly resulted in this, that they transmitted to all their offspring the very same nature, both as to body and as to soul, as was theirs after the Fall. In what manner, however, the soul contracts this evil, faith can safely ignore, because the Holy Spirit did not want to make it known to us through certain and clear Scripture testimonies.” Cf. also Baier’s brief historical remarks, I, 67, nota c; Luthardt, Dogmatik, 11th ed., p. 168 f.

136 The attempt to answer this question must lead either to Calvinism (the denial of the gratia universalis) or to Semi-Pelagianism and synergism (the denial of the sola gratia). — It is, of course, not sinful nor indicative of false teaching to pose the problem. In practically all periods of the Church the problem has been stated in various forms (Cur alii, alii non? Cur non omnes? Cur alii prae aliis?) But they sin and teach false doctrine who, with Melanchthon, the father of synergism in the Lutheran Church, would solve the problem by means of the “dissimilar conduct.” The Formula of Concord does not warn against acknowledging the problem, but it warns against any attempted solution of it. “In these and similar questions Paul fixes a certain limit (certas metas) to us, how far we should go, namely, that in the one part we should recognize God’s judgment … which we all have well deserved,” and that in the other part, “we acknowledge and praise God’s goodness to the exclusion of, and contrary to, our merit,” since God “does not harden and reject us,” who are certainly in the same guilt. — See the fuller discussion of this matter in the locus on “Conversion” and the locus on “The Election of Grace,” in Vols. II and III.

137 Reusch in his Annotationes in Baieri Comp., p. 52: “Reflection upon them is useless, the disputations about them unprofitable.” In recounting the futile labors of the Scholastics on the many questions which Scripture leaves unanswered, Dannhauer summarizes the result and practical benefits of their labors in the words: “The one milks the billy goat, and the other holds a sieve,” “unus hircum mulget, alter supponit cribrum” (Hodosophia, Phaen. XI, p. 667).

138 What Scripture has revealed concerning the condition of the soul between death and the resurrection will be presented in Vol. III.

139 In the language of the modern theologians who deny the inspiration of Scripture and want to draw the Christian doctrine out of their own Ego, the term “theological problems” has a different meaning. See Chapter 16, “Theology and Certainty,” p. 110.

140 Thus Winchester Donald, The Expansion of Religion, 1896, p. 125. This matter is fully presented in Lehre und Wehre, 1920, p. 270 ff.: “Die moderne Diesseitstheologie,” and in Lehre und Wehre, 1921, p. 2 ff.: “Das Christentum als Jenseitsreligion.” Here also the pertinent literature is mentioned. Cp. also Proceedings of the Michigan District, 1919, p. 44 ff. The creedless character of the modern social gospel will be discussed later.

141 Cp. R. Seeberg, Brauchen wir ein neues Dogma? 1892, and: Grundwahrheiten der chr. Rel, 5th ed., 1910, p. 61 ff. Theodore Kaftan, Moderne Theologie des alten Glaubens, 2d ed., 1906; Loofs, in R. E., 3d ed., IV, 753 ff., sub ν. Dogmengeschickte. Nitzsch-Stephan Dogmatik 3d ed., p. 2 ff.; 47 ff.; Horst Stephan, Glaubenslehre, 1921, p. 19 ff.

142 In Scripture the term is used to designate ordinances of both the Church and the State. Cf. Luke 2:1; Acts 16:4.

143 Trid., Sess. VI, can. 10, 11, 12, 20.

144 Guenther, Populaere Symbolik, 3d ed., p. 378 f.

145 See the decree of the Vatican Council, Popular Symbolics, p. 162.

146 See the chapters “The Means of Grace According to the ‘Enthusiasts’ ” and “Comprehensive Characterization of the Reformed Teaching of the Means of Grace,” in Vol. III.

147 More on this point under “The Representative Church” in Vol. III.

148 More on this point in the chapter “Holy Scripture and Exegesis” in the locus on “Holy Scripture.”

149 Walther, Pastorale, p. 81 f. [Fritz, Pastoral Theology, 1945, p. 334 f.]

150 Thus Scripture gives us reliable information on the metaphysical problems concerning the nature and the origin of things (Col. 1:16-17; Gen. 1:11-12), for which the philosophers have not yet found a satisfactory answer.

151 Luthardt, Kompendium, 11th ed., pp. 4, 6.

152 Lehre und Wehre, XIV, 76 f.

153 The flesh of the theologian would persuade him that his office as pastor or theological professor would be safer and be more respected if it were supported by the authority and power of the State. That is the reason why so many favor the “State Church” and are against the “Free Church,” despite the fact that according to God’s will the Church should function externally as a free Church. And the free Church theologians, too, are ever exposed to the temptation to resort to unchurchly means for the building of the Church, as witnessed by the “social affairs” in vogue here in the United States, the community churches, the clamor for a “strong church government,” and other phenomena.

154 Der Christliche Glaube, nach den Grundsatzen der evangelischen Kirche im Zusammenhange dargestellt, I, 16.

155 See p. 18.

156 The Bondage of the Will, St L. XVIII: 1680. – More on this in the next section.

157 Systema I, 42.

158 In this connection we call attention to Kirn’s idea that a man is sufficiently prepared for understanding the Gospel if he “seeks God and strives for moral perfection” (Eν. Dogmatik 3d ed., p. 37). The very opposite is true. Only he who despairs of achieving any kind of moral perfection, only he who knows that because of his moral disability and turpitude he is subject to eternal perdition (terrores conscientiae, contritio), is prepared to “understand” and appreciate the Gospel.

159 Frank, System der Christlichen Gewissheit, 2d ed., I, 128. Ihmels, Die Christliche Wahrheitsgewissheit, 1901, p. 8. Horst Stephan, Glaubenslehre, 1921, p. 66.

160 Cp. Luther on Matt. 13:15. St. L. VII:194 f.

161 They say: “In our day the orthodox doctrine of inspiration has hardly any significance in dogmatics. True, it is still being upheld by a few, e. g., Koelling and Noesgen, with some modifications. A theologian, strictly conservative, says concerning these laggards: ‘Their number is small, their labor unsuccessful, and their indignation at the comrades who are pressing forward on new paths impresses no one.’ … The rest of the theologians, including the conservatives, reject the old doctrine.” (Nitzsch-Stephan, p. 258.)

162 “Der Christliche Glaube, nach den Grundsaetzen der evangelischen Kirche im Zusammenhange dargestellt von D. Friedrich Schleiermacher,” appeared in print in 1821.

163 Ev. Glaubenslehre, p. 43 ff.

164 Die Kirche Deutschlands im 19. Jahrhundert, pp. 90, 84.

165 Schriftbeweis, 2d ed., p. 11.

166 System der chr. Gewissheit, 2d ed., I, 49. [In the English translation, System of the Christian Certainty, p. 46.]

167 Theol. Literaturblatt, Leipzig, 1922, p. 395. As to Bachmann’s phrase “as a matter of principle,” we would say that Frank certainly believed in this “full self-assurance” while he was lecturing to his students and writing books in his study. But from what we have heard concerning him and from what he wrote elsewhere we feel justified in assuming that his communion with God did not take place on the basis of his “self-assurance,” but on the basis of the “objective act of redemption” and the objective “Word of God.” Just as Frank assumes, in his Theologie der Konkordienformel (I, p. 135), that Melanchthon never believed in his synergism, so we assume that Frank never really believed in “the self-assurance of Christianity and its theology.” It should be noted, in passing, that we are not impugning the personal Christianity of all advocates of the self-assurance theory. While it is certain, according to Scripture, that this theory, when consistently applied in practice, precludes personal Christianity, it is also true, on the other hand, that in the field of theology, too, “felicitous inconsistency” plays a role; men do “keep a double set of books.” A few years ago German periodicals reported that a theologian who had been cultivating this same theology of self-assurance declared on his deathbed that now he found his entire theology summarized in John 3:16. He thus found it necessary to go beyond his own I, “beyond himself,” as Luther expresses it; he actually took his stand on a foundation outside himself.

168 Handbuch der theol. Wissenschaften, 2d ed., III, 65. The last sentence italicized by Zoeckler.

169 Frank asks the Christian to base his assurance on something within himself. His statement reads: “With the breaking through and the installation of the new I in the center of the personal nature, the  is gained” (op. cit., p. 133; Engl., p. 128).

is gained” (op. cit., p. 133; Engl., p. 128).

170 See the section above, “Open Questions and Theological Problems.”

171 See Ihmels, Zentralfragen, pp. 159-166. Also Kirn, Dogmatik, pp. 1-6.

172 With our old theologians we call the good works the testimonia Spiritus Sancti externa in distinction from the testimonium Spiritus Sancti internum, which consists in faith in God’s Word wrought by the Holy Ghost. The internal testimony of the Spirit and faith are one and the same thing. Cf. the fuller presentation in the chapters “Faith and the Testimony of the Holy Ghost” and “Justification on the Basis of Works,” in Vol. II.

173 Also in Frank’s theology the articles of the Christian faith “have been mutilated and crippled” by his use of the Ego method. That has been demonstrated in the article “Franks Theologie,” Lehre und Wehre, 1896, pp. 65 ff., 97 ff., 129 ff., 161 ff., 201 ff., 262 ff. The writer, Dr. Stoeckhardt, does not place Frank outright in the liberal wing of the theology of self-certainty. He acknowledges that “Frank permits certain elements of the Christian truth to remain.” That, however, is, as Stoeckhardt points out, “not due to his system, but to his inconsistency. This residue of Christianity has maintained itself against the antagonistic principle of the system. Frank and his system deserve no credit for these good features in his theology.” Stoeckhardt brings proof that Frank does away with the infallible divine authority of Holy Scripture at the behest of the Ego principle. While Christ and His Apostles unhesitatingly identify the Scriptures and God’s Word, Frank says: “I would not like to assume the responsibility of teaching a Christian that faith in the saving truth involves faith in the absolute inerrancy of Holy Scripture” (op. cit., p. 97). Frank also discards the satisfactio vicaria of Christ. Though Scripture expressly teaches that Christ suffered the punishment which we should have suffered (Is. 53:5; 2 Cor. 5:21; Gal. 3:13), Frank declares: “If substitution is made to mean that Christ suffered whatever condemned mankind would have had to suffer, the satisfactio vicaria falls to the ground, for the simple reason that that is not what Christ suffered” (op. cit., p. 138). Frank presents the doctrine of justification correctly when he describes the righteousness involved as the iustitia extra nos posita, but he falsifies it when he says that faith comes into consideration in justification, not merely as medium  , but also as the conduct of man, as an act of free self-determination. (Ibid.)

, but also as the conduct of man, as an act of free self-determination. (Ibid.)

174 Op. cit., 119, resp. 114.

175 Frank declares: “To the Holy Ghost I cannot appeal in connection therewith, since, of course, it is first a question whether what I receive is testimony of the Holy Ghost; exactly as I cannot appeal to sacred Scripture when it is in question how I come to admit the claim of Scripture to be sacred to me” (op. cxt., p. 143).

176 Frank cites Fichte’s Idealism, according to which the subject posits the object, in support of the scientific character of self-certainty. He says: “That is the abiding truth in the Idealism of Fichte” (Christliche Gewissheit, I, 61). O. Fluegel describes Fichte’s Idealism thus in Probleme der Philosophie und ihre Loesungen, p. 96: “Fichte holds, with Berkeley, that things exist merely in the mind, but he goes beyond Berkeley in that he no longer seeks an external cause which produces these conceptions of the mind but, expressly denying any such external cause, makes the mind itself the sole originator of the things which seem to exist outside of it.” Fluegel finds “only about two” inconsistencies in Fichte; H. Ulrici calls Fichte’s Idealism a “senseless one-sidedness” (R. E., 2d ed., XV, 381).

177 See Ihmels, Die christliche Wahrheitsgewissheit, pp. 124–167.

178 Zentralfragen, 2d ed., p. 166.

179 The influence of Schleiermacher in the United States is set forth in Strong’s long article on “The Theology of Schleiermacher as Illustrated by His Life and Correspondence,” in his Miscellanies, II, 1–57.

180 Lehre und Wehre, 1923, 89 f.

181 We quote from The Fundamentalist, Vol. II, No. 1: “The Radicals are set on substituting ‘evolution’ for creation, ‘the principle animating the cosmos’ for the living God, consciousness of the individual for the authority of the Bible, reason for revelation, sight for faith, ‘social service,’ for salvation, reform for regeneration, the priest for the prophet, ecclesiasticism for evangelism, the human Jesus for the divine Christ, a man-made ‘ideal society’ for the divinely promised kingdom of God, and humanitarian efforts in this poor world for an eternity of joy in God’s bright home.” Particular attention is called to a widely publicized sermon of Dr. Fosdick: “Dr. Harry Emerson Fosdick, for example, not only preached his now famous sermon here in New York on the question, ‘Shall the Fundamentalists Win?’ in which he repudiated the inspiration of the Scriptures, the virgin birth, the vicarious atonement, and the second coming of our Lord, but this sermon was then put into pamphlet form, and has been broadcast throughout the nation.”

182 The theologians who are opposed to “doctrinal progress” and “progressive theology” have been branded “repristinating theologians,” particularly the so-called Missourians (Preface to Lehre und Wehre, 1875, 1 ff., 33 ff., especially 65 ff.), but also others, for example, Philippi. Referring to Philippi, Hofmann gibes: “Let him who likes to take things easy keep on sleeping” (Schutzschriften, I, p. 2). —See the articles, “Die falschen Stuetzen der modernen Theorie von den offenen Fragen,” Lehre und Wehre, 1868, 97 ff. and “Die moderne Lehr entwicklungshaeresie,” Lehre und Wehre, 1877, 129 ff.